The Visual and Material Culture of Islam in Ladakh

Abeer Gupta

Ladakh is often romanticised as a homogenous Buddhist monoculture, situated around high-altitude monasteries and nomadic pastures. But Ladakh has an Islamic culture that dates back to at least six centuries and today constitutes over fifty percent of its native population. Rare, but with a little effort, a discernable pattern of Islamic visual culture can be found. While Ladakh has never really been cut off from the wider Islamic world, with Haj, visiting preachers and trade, it had largely constructed visible signs of its identity, on the basis of the indigenous local culture.

Over the past two decades, this has changed – partly because of increasing affluence and exposure to the outside world, partly for political reasons1, and partly due to the availability of new technologies in architecture and communications. With television and the Internet there is now rapid import of ideas of visual expressions of Islamic culture from the centre of the Islamic world. But local themes survive, in spite of large-scale material imports (such as cement, aluminum, steel and plastic) from India, indigenous crafts and motifs co-exist with a varying degree of usage. This essay examines some of these contemporary visual and material forms, from home and abroad, indicating the way Islam was perceived, practiced and how it is being constructed.

The religious spaces covered in this research reveal a variety of textile-based objects, like carpets, prayer mats and scrolls. These objects beyond their function were simultaneously used as decorative elements within these spaces. The older textile-based objects – such as carpets and prayer mats made in distant parts of central and west Asia – speak of interconnectivity of these regions in the past2. They also form the basis of an aesthetic inclination, a range of motifs, patters and colours, which became popular and are today part of Ladakhi society across religious lines. Certain patterns like the rgya-nag lcags-ri3 – the brick wall pattern inspired by the Great Wall of China and the yungdrung4 – the interlocking swastika motif – are today widely seen adapted on wood, plastic and paper designs. The secular spaces exhibit the transition from textile-based objects to paper-based formats such as posters and calendars using photo icons – reproductions of iconic figures and spaces. The printed forms are not only cheaper and easily accessible but are often personalized with growing ease of printing technology. The essay explores examples from both groups of objects – those imported and those produced locally – their procurement or production and the way they are used to identify their role within the religious landscape within a contemporary timeframe.

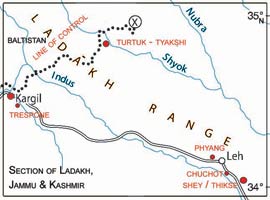

There are two sets of spaces covered in this research. First are the more secular spaces, such as shops and restaurants and second are religious spaces such as mosques, Khanqahs5, and Imambaras. These are spread across the districts of Leh and Kargil in Ladakh. In Leh district there are the bazars and religious buildings in Leh town, as well as villages south of Leh on the banks of the river Indus: Shey, Thikse and Chuchot. Chuchot is a rather large village consisting of Chuchot Gongma, Chuchot Shama and Chuchot Yokma. Also within the district of Leh, deep inside the Nubra Valley are Turtuk and Tyakshi, two small villages just before the Line of Control on the Shyok river before it flows into Baltistan, which is now in Pakistan. Turtuk still bears a distinctive Baltistani culture which is visible in the local architecture, food habits and clothes. Turtuk comprises two small hamlets, Yul and Pharol. Kargil District constitues of Kargil Town, which has today spread into a number of small adjoining hamlets such as Aba Gurung, Goma Kargil, Puyen and Baru. Also south of Kargil, along the banks of the Suru River, are villages such as Saliskote and Trespone. While the main business and administrative institutions are concentrated around Kargil town several old religious buildings are found in the hamlets which are repositories of religious iconography both old and new.

A brief context to the advent and evolution of Islam in the region is required in understanding the cultural process the objects are a part of. Islam was introduced to Ladakh through the visit of scholars, traders and various political arrangements. Historically, Ladakh often found itself in the midst of a power struggle between eastern and central Asian forces, between the Tibetans, Chinese, and Kashmiri kings, till the Dogras invaded Ladakh in the first-half of the 19th century and consolidated the state of Jammu and Kashmir. Explorers and religious scholars6 like Syed Sharafuddin Abdul Rehman, popularly known as Bulbul Shah, a Sufi of the Suhrawardi order, and Mir Syed Ali Hamadani of Kubrawi Sufi lineage, known as Shah Hamadan, travelled through Ladakh around the 14th century on their way to Yarkhand or China in search of writing paper for their manuscripts. Syed Mir Mohammad Hamadani’s son, Syed Mohammad Noor Bakhsh, his nephew, Zain Shah Wali, Meer Shams-ud-Din Iraqi and Baba Nasib-ud-din Ghazi visited Baltistan and Purig (Kargil) and passed through afterwards. They developed a small group of followers; the mosques at Shey and Tyaqshi (near Turtuk) were built by those associated to Mir Syed Ali Hamadani; the Khanqah of Chuchot Yokma and the Baru Khanqah in Kargil were built by the followers of Meer Shams-ud-Din Iraqi.

These structures were perhaps the modest and humble beginnings of an Islamic subculture in Ladakh. In the 15th century, a mass migration of Shias from Baltistan took place to the Indus belt just south of Leh in Chuchot7. They were not forced to adopt Buddhism and were allowed to practice their own religion. They constructed imambaras, khanqahs and mosques in Thikse, Shey, and Chuchot. Subsequently, more Muslims from Purig (Kargil) and Baltistan, and some Malas and Akhons (scholars and religious teachers) settled in the region. Urbanization and a cosmopolitanism that came with trade dates back to the same period when Islam was making an impression in Ladakh. Among several instances of political alliances, most prominently, in the 16th century, King Jamyang Namgyal (1555-1610) married Yabgo Sher Ghazi’s daughter, Rgyal Khatoon, as part of a peace treaty with the Baltistani kings. Though Queen Rgyal Khatoon’s son turned out to be one of the most prominent Buddhist kings of Ladakh, she continued to practice Islam and encouraged and helped infuse into Ladakh the performing arts and material crafts originating in Islamic cultures. Her son, King Senge Namgyal moved the capital from Shey to Leh around the 17th century and it developed as a trade hub, and by the time that Ladakh was under Dogra rule in the mid 19th Century Muslim traders8 had been settle in Leh for generations. Under the Dogras Ladakh was administered through three tehsils, Leh, Kargil and Skardu. Administrative and military officials were stationed in each of the tehsils, (districts) and the tehsildaar (collector) would shift between the tehsils for four months at each place. In the period between 1950 and 1970 after Ladakh was reconfigured and the Line of Control was formed, it was a restricted area but large numbers of teachers, administrative staff from Kashmir, along with the Indian army moved in. Since the mid 1970s when Ladakh was opened to civilians from the rest of India and foreign tourists a much more radical transformation has taken place. While Leh in spite of its growing Islamic population has benefitted from maintaining a Buddhist flavour, Kargil has continued to embrace a more evident Iranian influence.

The Islamic population9 of Ladakh, today, belongs to Shia, Sunni, Ahl-e-Hadees (a sub-sect within the Sunnis) and Nurbakhshi (a sort of Sufi) sects. The majority of Shia enterprises and land holdings are concentrated in the district of Kargil and in Leh district in villages such as Chuchot, Shey, and Phyang. The Shias of Ladakh mostly trace their origins back to the region of Baltistan. But though Baltistan embraced Islam around the 13th Century, their language and culture continued to have strong affiliations with Ladakh. The Nurbakshis are found mostly in the region adjoining Turtuk and in Disket in the Nubra Valley. The Sunnis, either descendants of Kashmiri merchants or those who came from Yarkhand are concentrated mostly in Leh town. The community of Arghons10 came into being when these traders married local women and settled there. Leh being the district headquarters and the main commercial centre in the region, houses families from all the sects primarily for jobs and education. It also attracts large populations of seasonal migrant labour and businessmen across the sects. Seasonal Kashmiri businessmen, control the market of antiques, second hand clothing, and various contrabanned items and men from Doda and Kisthwar (in Jammu), who, for several generations have worked as masons, are largely Sunnis. They are concentrated in the Old Town11 of Leh and some of its adjoining areas, where cheap rented accommodations have come up. This area has also become the hub of migrant workers from Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, who work as barbers, carpenters, and tailors – there are large numbers of Muslims among them. The essential markets of Leh are all situated along the contours of the Old Town and it is here that Islamic enterprises flourish and display and range of popular visual culture.

While the spoken language is Ladakhi across the communities, the Islamic communities have adopted the Urdu script. Evolving religious norms have rendered certain practices unacceptable, such as singing and dancing – which was once popular among the Islamic communities. With growing affluence from a tourism led economy, and increasing number of young Ladakhis moving to cities like Jammu and Chandigarh for their education, complex new notions of identity are forming both at home and beyond. Sonam Chosjor, in Beyond Kashmir, Understanding Ladakh in Rekha Choudhri (ed.) Identity Politics of Jammu and Kashmir, (Vitaasta, 2010) highlights the politics of Ladakh within the larger conflict in Kashmir, the movement of gaining Union Territory status and the alienation of Muslims of the region. Yoginder Sikand, in Buddhist-Muslim Relations in Ladakh (2006, 2010)12 further elaborates on the communal strife in the late 80s, and the inter-regional politics of Leh, Kargil and Kashmir. These issues along with a rapid reception of contemporary forms of west Asian Islam are creating a lasting impact on the otherwise plural society of Ladakh.

Section 2: Popular Visual Culture and Contemporary Enterprise: Printed and Framed Objects: Calendar and Posters

Belting, (2005) speaking of ‘mediality’, mentions the importance of not only the contents of an image, but also the circumstances under which it survives, i.e. how it is read, interpreted and sustained in the memory of those on whom it works.

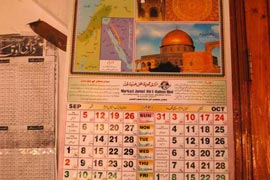

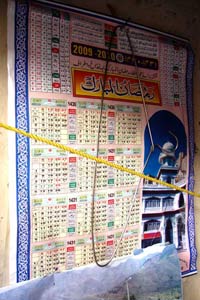

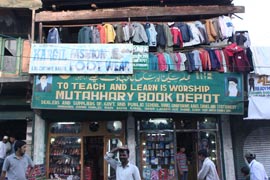

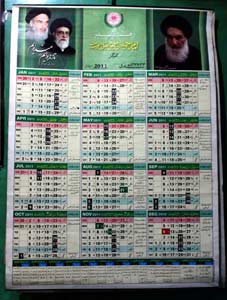

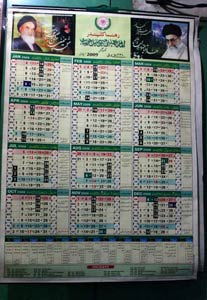

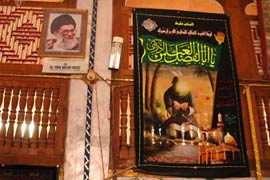

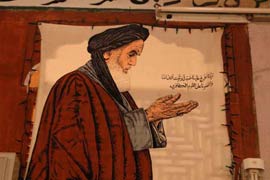

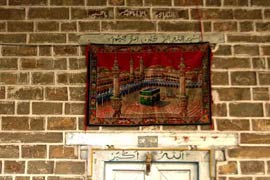

Inspite of the growing ratio of Islamic population in Ladakh it continues to be largely perceived as a subculture and its practices largely looked upon, as peripheral. Except in and around Kargil town where it is the dominant practice. An example of this is the drive from Leh town to Hemis Monastery along the road, which passes through Shey and Thikse. Though most visitors to Ladakh use this route to visit the grand monasteries but fail to register one of Asia’s longest villages, minutes off the highway. Set along the banks of the Indus, Chuchot is almost entirely Shia and is an ethnically Balti settlement, which dates back to at least five hundred years. What does come to notice are posters of the Kabah in Mecca, Al-Masjid al-Nabawi, Medina, or calendars of the Ayatollah Khomeini (Figure 01) and his successors in restaurants along the highway from Kargil to Leh, and in certain shops, (Figure 02) once in the main bazaar in Leh.

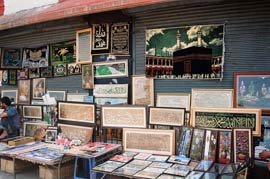

These are the simplest and most easily recognizable images that set the space immediately apart from its Buddhist counterpart and make the visitor aware of the presence of this large community. So while for the tourist these images could be markers to identify an Islamic enterprise, for the locals the images featured on these calendars operate beyond simply a religious or ritualistic context, but as signposts of a communal identity – what Patricia Uberoi (1993) calls the ‘construction of an appropriate past within the context of cultural nationalism.’ The main market around Jama Masjid in Leh displays a range of Sunni iconography such as the calendar of the Markazi Jammat Ahl-e-Hadees Hind, (Figure 03) with a photo icon of the Al Aqsa mosque or the calendar of Kanwal Spices, a leading spice manufacturer based in Anantnag in Kashmir, which uses the image of the mosque in Medina.

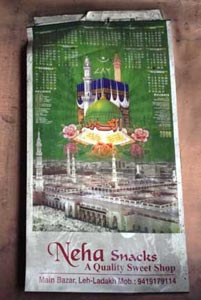

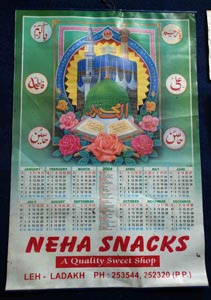

However, these particular objects work outside any moral discourse of aesthetics. Rather, as Gell (1992) suggests, it is etched within a technical system “orientated towards the production of social consequences which ensue from the production of these objects. The power … stems from the technical processes they objectively embody.” A curious example of this are calendars which till recently were produced every year around Diwali by a Hindu business family, which runs a sweets and snacks outlet called Neha Snacks in the main bazaar in Leh (Figure 04 & 05).

They, a minority within Ladakh, print a range of calendars with Hindu, Muslim, Sikh and Christian imagery for each of the other minority communities in Ladakh purely for local consumption. This business family is known as Lalas – Hindu traders from Hoshiarpur who were once part of the land trade and had assets in Yarkhand but settled in Leh in the 1950s. This particular shop has a long involvement with the local community. The current owner’s father, Lalit Gupta, owned one of the first photography shops in Leh called Lalit Studios. In their calendars, though, they have chosen to use more familiar and widely accepted images of the Kabah and the mosque in Medina.

In recent years, with the growing availability of digital designing and printing technology, the region has also started producing their own variety of religious iconography. A host of new local calendars designed within Ladakh, though often printed in Srinagar or New Delhi, have started iconising a number of regional buildings. The advent of technology in the past decade and the expertise to visualise and create local iconography is truly an ‘empowering condition,’ (Bhaba; 1994: 227) for the people of Ladakh who have for long had to depend solely on imported religious artifacts. Today, the mass production and distribution of these calendars mark the growth of an independent visual representation scheme, which is creating an identity for itself within the overwhelming outside influence.

The transition can be seen in the calendars of Leh Book Depot, which has moved from the image of the mosques of Mecca and Media (Figure 06) to the mosque at Shey. The Anjuman Sunni Committee, Leh Book Depot and M/s K2 Adventures have now started bringing out their own calendars during Ramadan. Leh Book Depot and M/s K2 Adventures have both used the iconic Shah Hamadan Mosque in their calendars (Figure 07)– with an almost identical layout but different images for the mosque. This mosque has been associated with the Sufi saint, Shah Hamadan, who in AD 1381, is believed to have visited Ladakh on his way to Kashgar and China. The Muslim queens of Ladakh are said to have used this mosque and both Shias and Sunnis today visit this mosque. In the calendar made by Leh Book Depot, a photograph of the renovated building has been used, which is currently part of a project undertaken by the Directorate of Tourism to convert the premises into a botanical garden. A local graphic design studio has added an image of a green dome into the photograph – which does not exist today. M/s K2 Adventures, on the other hand, directly uses the image supplied by the Tourism department with the development plan of the shrine. The same photograph is found displayed outside the shrine in Shey. The Anjuman (Ladakh Sunni Muslim Association) quite naturally has chosen to iconise the Jama Masjid (Figure 08) in its renovated form, which, as mentioned before, has come to acquire the most significance in the region. While the larger business enterprises and more religious organisations continue to the use the more iconic mosques of West Asia, it is a smaller local enterprises that have begun to experiment with images of local importance.

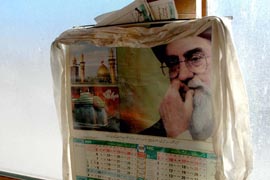

Images of Ayatollah Khomeini in the form of posters or old calendars, which have been framed and retained (Figure 09), are popularly found in the homes and religious spaces of the Shia community. The photographs of the Ayatollah and representation of West Asian mosques are now being frequently used as part of regional communication and have been incorporated within a local cultural process.

Examples of this are posters (Figure 10) made by the Husain-e Youth Committee (Leh Shia Students) and local hoarding and banners such as the Imam Khomeini Chowk in Thikse and Kargil (Figure 11 & 12). In each of these cases, the image or the name has become a signpost for Shiite practice.

By drawing attention to various examples of images and photo icons prevalent in the subcontinent, Alfred Gell (1998) elaborates how objects (printed/framed images of mythological or real characters) acquire human traits, or become God-like within social networks, to the extent that artifacts and humans occupy an almost equivalent position. In Ladakh’s own unique way, this can be seen happening as people often garland these photo icons with Khatags — a ceremonial white Buddhist silk scarf — that is offered to show respect or admiration. These white scarfs – the ones used by the Muslims usually do not have the Buddhist motifs woven in them – can be seen used widely adorning photographs, (Figure 13) shrines as well as door knobs or important buildings.

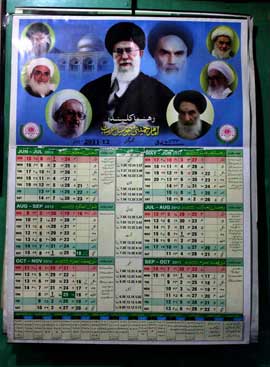

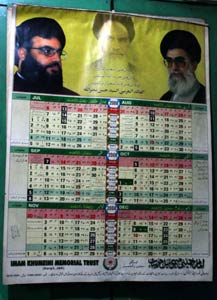

Noteworthy examples of Gell’s idea are the IKMT13 calendars in Kargil (Figure 14 a, b, c, d & e), which have consistently used the photo-icon of the Ayatollah and his counterparts and their calendars, and are commonly retained across Ladakh as a religious artifact. The Imam Khomeini Memorial Trust is a rather influential body, which controls religious, social as well cultural organization in the region. Though the design can be seen evolving to dramatise the idea, the communication remains simple and direct. This local iconisation of the image is evident from its display in almost all shops, homes as well as religious buildings, in the region.

Printed objects: Posters

The grand Imambara in Chuchot Yokma has become a regional landmark for the Shias, just like the Jama Masjid in Leh has for the Sunnis. Numerous legends associated with this building speak of a cultural past that often goes beyond religion. In present day though, it has developed into a storehouse of imported, digitally reproduced Shia iconography, which contributes to the construction of a ‘desired religious landscape’ (Oberoi 1993).

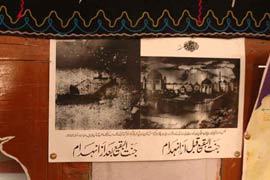

Two textile-based scrolls, know as parcham, imported from Iran adorn the walls of the Imambara in Chuchot Yokma. One of them shows Imam Husain carrying the six-month-old Ali Asgar, (Figure 15) who was martyred during the battle of Karbala; the other depicts Abul Fazal Abbas (praying) (Figure 16), with images of the dual shrines of Imam Husain and Abul Fazal Abbas below it. Both these textile scrolls have calligraphy with the faces of the iconic characters blurred out. Two rare posters found only in the Chuchot Yokma Imambara, also from Iran: depicts the graveyard, Jannat-ul-baqi, in Medina, Saudi Arabia, (Figure 17) which has been demolished several times by the Wahhabi forces and developed as a space significant to the construction of Shia identity. The other is a map of sacred spaces related to the followers of Islam in West Asia (Figure 18). These reinstate a culture negotiating their identity by pointing at the ‘presence of an absence … images are present in their media, but they perform an absence, which they make visible.’ Belting (2005). These image work in a clear linear fashion: the image becomes a point of departure, the building, the site of that absent, imagined land.

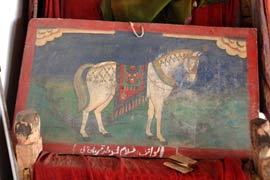

The most popular image, though, is of Imam Husain’s horse, Zuljanah, mass-produced as posters (Figure 19) or calendars (Figure 20) in India. But the Imambara of Chuchot Yokma still bears one of the oldest examples of this image in Ladakh. Brought back from Iran, this piece was hand-painted on wood (Figure 21). Pieces such as these worked as the initial inspiration to the hand-embroidered textile scrolls (discussed later — with additions of various elements that corroborate the tales from Karbala). But the ideal example of the appropriation of these narratives and characters into the western Himalayan landscape is a rare hand-painted Zuljana in Tibetan style (Figure 22) at the Khanqah of Chuchot Gongma. Painted in softer shades of blue and clouds rendered in a way commonly seen in Thangkas, it is an example of the confluence of religious content and regional representational techniques.

Section 3: Popular Material Culture and the transformation of trade patterns: Textile based objects

Ladakh, situated almost centrally between northern Indian and central Asian trade routes, was, in the past, bustling with socio-economic activity14. Ladakh was important not only for its prized commodities such as pashmina, shahtoosh and gold; it was a crossing of major trade routes, which connected the Arab world, Lahore, Delhi and Srinagar to Tibet and China. It was a difficult and vast terrain, and control over the region determined the geo-politics of the region. Within Ladakh, traders from western Ladakh bartered basic supplies in Changthang in eastern Ladakh for pashm15 and wool (the raw fibers), and then bartered them with Kashmiri traders. Balti traders from Skardu brought dried apricots, vegetables and butter and traded them in Leh with rice, tea and sugar. Such practices, prevalent till recently, were perhaps the key in determining Ladakh’s unique culture of plurality and exchange. With Jammu and Kashmir acceding to India, the borders were redrawn and Srinagar became the centre of a new political discourse. In Ladakh with democracy came a new federal economy, various state departments, bureaucrats and a new set of inter-regional politics; and nearly 20 years (till the mid-1970s) of being cordoned off as the borders had become too sensitive and had to be heavily guarded by the Indian army.

In Ladakh, Culture at Crossroads, Monisha Ahmed and Claire Harris, speak of the ‘materiality of everyday such as dress, jewellery, portable objects, articulate the complexity and fluidity of Ladakhi life’ (Harris, Ahmed, 2005). Essays in that volume, further elaborate contribution of Islamic communities to architecture, the existing wood, textile and metal crafts. They also point to the importance of examining their relation to the construction of a larger cultural process, through the confluence of Tibetan and Kashmiri styles in forms and materials. The Balti people have traditionally been credited for the introduction of certain carpentry techniques, (Zubdavi, 2009) to make rafts, boats and woodwork. Shinkan – the Balti carpenters, built the Hawa Mahal in Chiktan Palace; most notably, Tsandan (alias Ali Singhay), the Balti craftsman, built the Singhay Zongmo, the wooden lion gate of the Leh palace. In recent times masons from the village of Trespone, near Kargil are one the unique self trained architects and builders who have constructed not just the elaborate new mosques of Ladakh but other significant commercial buildings and family of Ghulam Sultan Chungkha still produce some of the most exquisite gold and turquoise jewelry unique to the region.

The transformation in the passage and control of goods had an influence on not only the life and livelihood of the region; it also had a profound effect on how they perceived themselves – their indigenous identity. A flood of supplies such as food grains, clothing materials, kitchen equipment and daily ware from the subcontinent made their way into Ladakh in trucks from Srinagar. The supplies meant for the growing number of various military forces started gaining popularity among the locals. Some border trade with China continued but eventually died out with growing tensions. While on the one hand, cheaper imports reduced local produce (such as agriculture, metal ware, pottery, textiles), on the other; the multi-directional interaction was confined to a one-way passage from Kashmir. Only a small number of indigenous craft traditions, such as the choktsey16 (carved wooden tables), khabdan17 (pile rug carpets) and jewellery (with turquoise set in gold with pearls) have survived and continue to be used by both the Buddhist and Muslim communities of Ladakh. The range and variety of objects that were used by the Islamic cultures of the region were also part of this transition. At one time, utensils, silk and carpets from China, Yarkhand, to as far as Turkey, found its way into homes and religious spaces through trade or pilgrimages. However, these became rare and were replaced by those produced in the plains of India via Kashmir or smuggled across the Line of Control from Pakistan.

Srinagar has been a significant religious centre for Sunni Islam in the region; it has developed a market for a range of mass-produced objects, such as prayer mats, scrolls, wall-hangings and framed iconography. A range of products, from local hand-crafted products to imports from Iran, Saudi Arabia or Dubai, can be found in the shops in Lal Chowk (the business centre of Srinagar along Residency Road) (Figure 23 & 24), the markets around Jama Masjid, Nowhata and around important shrines such as Makhdoom Saheb and Dastgeer Saheb. Such products have made their way both into religious spaces as well as into homes in Ladakh. In the Shah Hamadan mosque, Shey, at the head of the congregation near the mihraab is an expensive silk carpet donated by a devotee. Woven in Kashmir, it has a floral Persian design and is placed on a namda — a felted rug with chain-stitch embroidery, which is also produced in Kashmir and is made of course sheep wool. Another silk prayer mat, with a mihraab design produced in Kashmir, is at the Ahl-e-Hadees mosque in Turtuk (Figure 25).

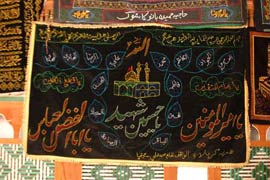

Kargil, on the lines of Srinagar, has developed into a centre of dissemination of a range of Shia religious iconography, which is imported from Iran and reaches Kargil through Srinagar. There is an array of posters and calendars with popular motifs such as of Zuljanah (the horse) and The Ayatollah, Imam Khomeini and Ayatollah Syed Ali Khamenei, the present spiritual head. Notable among these are the long textile scrolls made in Iran with the names of twelve Imams embossed on them (Figure 26 & 27), which run all along the walls of nearly all the imambaras in the region.

Textile-based objects: Carpets

The Jama Masjid in Leh Bazar was built on a portion of the king’s main field, known as tetres, the remaining part of which is where the main bazaar came up. The mosque was completed during the reign of King Deldan Namgyal under the orders of the Mughal emperor, Aurangzeb, in the mid-17th century after he helped curb a Tibetan Invasion. This became a hub of Sunni traders from Kashmir, Yarkhand, and, over several centuries, developed a unique repository of carpets from Yarkhand, Tibet, Kashmir and even Turkey. This building would set the standards of taste and general aesthetics of the Islamic population in its time. The interiors of the main mosque have the original beams of poplar and a pulpit, which have been painted in Tibetan style. The main door though, also similarly painted, has been painted green more recently. The original building, made of wood and mud bricks, has been replaced by a concrete structure with a new eastern wing still under construction with a hamam (traditional method of heating) added to it. It is here in the new wing that this rare collection of carpets has found its place.

Floor covering has traditionally been an important aspect of buildings in the region not just for insulation but also as a key element of decoration and adding colour to the monochrome surrounding. The old carpets are mostly made of wool. There are rectangular – around 8 by 12 feet, square – around 10 by 10 feet, and smaller rectangular rugs resembling the size of prayer mats (Figure 28). There are mainly knotted carpets from Kashmir, Yarkhand, a prominent Tibetan pile rug and kilims or flat tapestry — woven carpets — from central Asia (Figure 29). Within them an array of motifs from across central Asian cultures, such as the swastika or the Chinese brick wall, geometric Islamic motifs as well as floral patterns made in Kashmir, can be found.

The main prayer hall of the Jama Masjid has two antique Yarkhandi carpets, which are only used during the holy month of Ramadan. They were made to order (38 feet 6 inches by 7 feet 7 inches) by Khwaja Hyder Shah and Nassir-ud-in Shah in the mid-19th century. These carpets are designed as rows of smaller prayer mats, each marked off with the motif of a mihraab. Inside the mihraab on a blue base is a multi-coloured floral pattern. This year, five replicas of these carpets were commissioned and completed around Eid 2011 to cover the remaining floor space of the main mosque.

|

|

Textile-based objects: Prayer mats

The elaborate carpets of Jama Masjid might not have found their way into some of the smaller mosques, which were used by local communities. In these spaces, an assortment of jaenimaz (prayer mats) is commonly seen covering the floors. While the carpets seen at the Jama Masjid speak of a certain regional exchange, the jaenimaz is a personal contribution. Brought back from pilgrimages as mementoes, a range of mats from Iran and Saudi Arabia can be found. The older prayer mats were hand woven cotton or wool, with subtler colours of natural fibres (Figure 30) and often had geometric patterns along with floral motifs, which were symbolic of the Persian gardens. In recent years, Pakistan,

China and Indonesia have developed as mass producers of a range of prayer mats, which are picked up from trips to Delhi and Srinagar. With the exception of rare silk mat from Kashmir, the newer ones are more complex designs (Figure 31) of iconic mosques, of the Kabah in Mecca fused within the form of mihraab. The most common colours used in these prayer mats are red, blue and green made of synthetic yarns of acrylic. Inside the Khanqah at Chuchot Gongma, the Shah Hamadan Mosque at Shey, the Khanqah in Chuchot Yokma, and the Nurbakshi mosques in Turtuk a mix of old and new prayer mats can be seen.

These payer mats and carpets apart from being decorative objects can be looked at as serving another function. The landscapes or buildings depicted in these textile works are actively marking off spaces that are discontinuous to the spaces within which they exist. They are cut out and made to stand apart within a parallel temporal space. Hans Belting (2005) mentions the role of visual media within human interaction and how the individual actually processes it. He says, “Some languages, like German, distinguish a term for memory as an archive of images (Gedachtnis) from a term for memory as an activity, that is, as our recollection of images (Erinnerung). This distinction means that we both own and produce images. In each case, bodies (that is, brains) serve as a living medium that makes us perceive, project or remember images and that also enables our imagination to censor or to transform them.”18

Textile-based objects: Wall hangings

Calligraphic textile scroll bearing the Chahar qul (Figure 32)— four surahs from the concluding chapter of the Quran, or Ayatulkursi, (Figure 33) the verses from the third chapter of the Quran — are popularly seen in the markets in Srinagar. About 2.5 feet in height and a foot in width, these verses are woven in gold and black over a green background. In recent times, apart from the more expensive imported ones from Iran, a range of local versions have evolved — produced locally with less detailed embroidery or sometimes merely reproduced in colour on paper. Textiles with the images of Kabah, Mecca and Medina mosques are also common — the earlier, more elaborate ones would be embroidered with gold tread on black or green velvet. The ones commonly available now are mostly machine-made or woven. Some of the more impressive imported versions of the calligraphic scrolls can be seen adorning the walls of the Khanqah at Chuchot Gongma and the Shah Hamadan Mosque at Shey (Figure 34).

But the most common textile scrolls that preceded the posters or photo icons in Ladakh are of the Kabah at Mecca, usually brought back as mementoes from Haj. A variety of designs can often be seen accumulated over decades upon the walls of various mosques such as the old and the new Nurbakshi Mosques at Turtuk (Figure 35 & 36).

The hand-made alams at the Imambara in Chuchot Yokma

The Imambara in Chuchot Yokma got a modern-day make over in the mid-80s in a Turko-Iranian style. This Imambara is one of the most revered Shia buildings and still bears an unmistakable local flavor. Seen especially in the construction of the roof in the use of talu (wicker branches) or boards, which is widely used in Kashmir to cover the crossbeams of the roof. The concrete pillars are a local interpretation of the wooden columns and brackets seen elsewhere but scaled up to fit the much larger structure. The painted wall panels and ceiling brackets also reflect a local style. The central dome is clearly of west Asian influence, where a lantern (skylight – a common local feature) has been merged into it. The old pinjrakari19 (lattice work) screens — which have been retained from the older structure — are a direct influence of Kashmiri craft and further, the turned-wood railings are of the machine-made variety introduced during the Dogra period (it can be seen in many grand structures in Srinagar built around of the 20th century). The new main door has a rectangular repeat of a chinar tree (completely absent in Ladakhi landscapes), an example of contemporary woodcarving from Kashmir. Both the motif and the material (walnut wood) are from there. The main door has two swords of Hazrat Ali, two moons and the minaret between them rendered among verses from the Quran, above it. One rare and unique aspect are the two minarets, which have incorporated the local woodcarving both in terms of the wooden gallery but also the checkered motif – cholo20 – commonly seen in Tibetan carving as well as local Ladakhi pile rugs, onto the structure at the base of the gallery. The new gateway — which has replaced the green painted iron gateway — fit more into the notion of traditional architecture; it uses the three-layered carved wood panel (shinstag) and concrete pillars rendered in white.

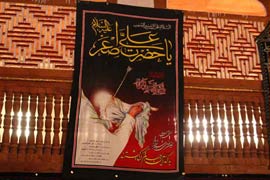

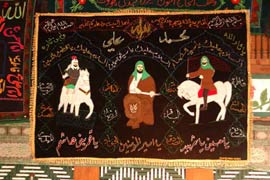

Unique ranges of locally hand-embroidered scrolls – alams, are found displayed at the Imambara in Chuchot Yokma. These scrolls were made by the women of Shia villages across the region and often had the name of the village, and person commissioning it embroidered on it. The base of these alams, mostly a black cotton or velvet cloth with the local ari (chain-stitch) embroidery to mark the grieving occasion of Muharram. These alams were used as flags and banners at the head of the procession of mourners from various villages. Originally popular in Saliskote, Trespone region of Kargil and Chuchot near Leh, they are rarely manufactured today. These were narrative scrolls that pictorially represented the Tragedy of Karbala and hailed the sacrifice of Imam’s family through symbols of Mecca and Medina mosques, zuljanah, Imam Husain’s sword in red, the severed hand of Abul Fayaz Abbas and the mushk (water bag), a headgear on the ground symbolising the fallen martyr. Palm trees, sparse desert shrubs and camps/tents are used to represent the scene of war (Karbala) in the desert (Figure 37). Calligraphic representation of ‘Ya Husain’ along with Mohammad, Allah, Fatima, Ali, Husain and the name of the twelve Imams are seen in several scrolls (Figure 38). Among them is a pictorial depiction

of Hazrat Ali (in the centre) (Figure 39) mounted on a lion with this double-edged sword, and Imam Hasan and Imam Husain on the left and right, respectively, on horses and battle gear and holding red and green flags. Notable in the format of display (Figure 40) (apart from the rest that are randomly hung on the left and right walls) are the alam and a scroll of the Kabah just above the main entrance of the Imambara. A visual hierarchy has been created: by the scroll of the Kabah (symbolic of Allah), above Mohammad (in calligraphy), above the twin-faced sword (symbolic of Imam Ali), the names of the twelve Imams below and finally the three mosques.

The handmade scrolls seen at Chuchot Yokma and the image of Kabah, seen on the imported wall hangs further corroborates the role of these forms of visual media as together “they perform an absence, which they make visible.” The surface of these cloth banners provided the first medium to etch out spaces, and buildings. The first minars and domes to me created in Ladakh where on these banners which helped evoke a desired landscape and narratives associated with it. These objects helped perceive, project or remember images till television and the Internet gained popularity. In recent years large printed banners are designed locally but printed digitally on flex in Srinagar and have replaced these scrolls. The time and embroidery skill required to create the textile scrolls have become rare.

The Imambara of Saliskote, in Kargil is yet another such repository of alams, which display the evolution of these banners. From the intricately hand embroidered ones, to the machine made, or printed ones to the contemporary ones which are printed on flex. They also display the evolution of a religious narrative, as one sees the traces of the Islamic revolution in Iran on some of them.

|

|

Conclusion – Regional popular culture and Religion

Ladakhi Muslims were traditionally part of a strong regional culture, with a common language and dress. Life was determined by the geo-climatic conditions and fashioned by resources available in the region. Ideas that came with Islam influenced and produced a consistent subculture. Ladakhi Muslims adopted vernacular architecture and constructed unassuming functional buildings using local materials and forms – cubical structures made of wooden beams and mud bricks. While a few such buildings have been preserved and restored, most of them have been renovated into spacious concrete buildings with minarets and domes. This reconstruction of old buildings got going with the advent of western building technology and materials since the 1980s, to accommodate the changes within the community which had grown in size, constitution and affluence. There was more interaction with sub-continental and mainstream Islam, and with people travelling to west Asian pilgrimages more often, the idea of an Islamic visual identity was swiftly redefined. Globalization and a gradual dilution of traditional practices eased the impact of Wahhabism and post revolution Iran into the interiors of the region. And along with vernacular architecture, performing arts, and use of regional objects steadily declined. But despite the Turko-Iranian influence in the construction of Islamic buildings certain indigenous visual forms and regional motifs are being retained and reinterpreted. The local aesthetic inclinations in the use of carved wooden doorways, which include Tibetan and Central Asian motifs, and Ladakhi style execution of pillars compliment foreign features like arches, minarets and domes.

The distinctions in objects brought back to Ladakh from pilgrimages and those developed locally point towards the evolution of a unique local Islamic aesthetic. It exemplifies how a regional culture continues to appropriate a global religion into its fold. How it continues to negotiate a regional identity within visual culture of Islam. With the rise of exchange of visual expressions, videos of celebration of Muharrams from across Shia cultures are widely circulated and are often seen in Ladakh as well. But the procession that takes place every year is Chuchot is still marked by a few unique Ladakhi features. The procession is lead by a white horse, symbolic of Zuljanah, and mourners carry tabuts, wooden boxes that symbolize the coffins of Imam Husain and his family, to the congregation at the imambaras. Both the horse and the tabuts are still adorned with Chinese brocades and Ladakhi jewelry adorns the tabuts of the martyred ladies, and the dirges sung by the mourners are still in the local language.

The textile-based objects such as carpets, prayer mats, and wall hang, display a much wider historical interaction and the images on them first invoked spaces only heard of from teachers or pilgrims. The carpets from Yarkhand at Jama Masjid, Leh inspired beauty and awe, and host of other imported iconography seen at the imambaras in Chuchot or Saliskote aided religious education. The calendars and posters with Islamic iconography, bought from the streets of Delhi or Srinagar, have been used as a communal signpost but often they decorated a cracked wall. But, images such as the Tibetan rendering of Zuljanah, or the calendars with the images of Shey Mosque or The Jama Masjid in Leh – the ones conceived and designed in Ladakh display the great pride the people take in their own cultural heritage.

Bibliography

Ahmed Monisha and Harris Clare, (ed) Ladakh: Culture at the Crossroads

Ahmed Monisha, Living Fabric (Orchid Press, 2003)

Shahzad Bashir – Nurbakhshis in the History of Kashmir, Ladakh, and Baltistan: A critical View on Persian and Urdu Sources, IALS, Rome

Belting Hans, 2004, Towards Anthropology of an Image

- 2005, Image, Medium Body: A New Approach to Iconology, University of Chicago

- 2001, Bild-Anthropologie. München, Fink

- 1994, Likeness and Presence. Art History of the Image before the Era of Art. Chicago U.P., Chicago

Bhabha, Homi K (1994) The Location of Culture, London: Routledge

Coote, Jeremy and Shelton, Anthony (ed) 1992, Anthropology, Art and Aesthetics, Oxford University Press , Oxford, New York

Gell Alfred, The Technology of Enchantment and the Enchantment of Technology

Gerhard Emmer – The Conditions of the Arghons of Leh, IALS LEH 2007

Fewkes, Jacqueline H (2009) Trade and contemporary society along the Silk Road: an ethno-history of Ladakh, London, New York, Routledge

Gell Alfred, 1998, Art and Agency, Claredon Press, Oxford

Grist, Nicola – Urbanisation in Kargil and its Effects in the Suru valley

Grist, Nicola – Twin Peaks: Two Shi’ite Factions of the Valley

Gupta, Radhika – Asad Ashura: an Indigenous Cultural Tradition, IALS Kargil

Hasni, Ghulam Hasan – Common Proverbs in Baltistan and Ladakh, IALS Kargil

Khan, Raja Iftekhar Hussain Ali – The Impact of Balti Culture on Jammu & Kashmir and Beyond, IALS Leh 2007

Mohammed, Jigar – The Mughals’ Relations with Ladakh during the 16th and 17th Centuries, IALS Kargil

Mohammed, Jigar – Mughal Sources on Medieval Ladakh, Baltistan and Western Tibet, IALS Leh 2007

Munshi, Nasir Hussain – A Lost Legacy: Forms of Dance and Music in Baltistan, Kargil

Pandit, M A (1978) Mosques and Imambaras in Cultural Heritage of Ladakh – Ministry of Education and Social Welfare, Govt. of India. Publication No. 1182

Pinault, Davit – Muslim Buddhist Relations in a Ritual Context: An Analysis of the Muharram Procession in Leh Township, Ladakh, IALS Arhaus

Pinney, Christopher and Thomas, Nicholas (ed) 2001, Beyond Aesthetics: art and the technologies of enchantment, Oxford, Berg

Pinney Christopher, Piercing the Skin of the Idol

Pirie, Fernanda (2006) Peace and Conflict in Ladakh - The Construction of a Fragile Web of Order, Brill’s Tibetan Studies Library, 13, Leiden; Boston: Brill

Pirie, Fernanda & Beek, Martijn van (2008) Modern Ladakh Anthropological Perspectives on Continuity and Change Leiden; Boston: Brill

Rizvi Janet, Ladakh: Crossroads of High Asia (pg 209‐212)

Rizvi Janet, Trans-Himalayan Caravans: Merchant Princes and Peasant Traders in Ladakh, (Oxford University Press, 2001)

Salik, Syed Bahadur Ali – Balti Folksongs Referring to Ladakh

Sheikh, Abdul Ghani – Islamic Architecture in Ladakh

Sheikh, Abdul Ghani – A Brief History of Ladakhi Muslims (Part II Islam in Ladakh and Tibet)

Sheikh, Abdul Ghani – Tradition of Sufism in Ladakh, IALS Rome

Sheikh, Abdul Ghani – Kargil from the Perspective of Historic Travellers and Government Officials, IALS, Kargil

Sheikh, Abdul Ghani – Ladakh and its Neighbours, Past and Present, IALS Leh 2007

Sheikh, Abdul Ghani – Transformation of Kushko Village, IALS Leh, 2007

Snellgrove, David L & Skorupski, Tadeusz (eds) Cultural Heritage of Ladakh, Volume One: Central Ladakh, Aris and Phillips Ltd, Warminster, England - Chapter One: Cultural Background: Geographical Factors

Zubdavi, Sheikh Mohammad Jawad – History of Balti Settlements in the Indus Valley around Leh, IALS Kargil

Articles from Ladags Melong

‐ A Qayoom Ladakhi – Jama Masjid of Leh, Summer 1994

‐ Abdul Ghani Sheikh – Ladakh’s Link with Baltistan, Summer 1996

‐ Abdul Ghani Sheikh – Muslim Monuments in Ladakh, Spring 1997

‐ Mohd. Sharif – The Holy Month of Ramazan, January 1998

‐ Zain‐ul‐Abidin – Different Religions, Common Culture, September 2001

‐ Abdul Ghani Sheikh – Eid‐ul‐Fitr, December 2001

‐ Tashi Morup – Masons and Mosques, April 2002

1. Formation of the Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council in 1995 and LAHDC - Kargil was set up in 2003 – ensured better representation and funds of the communities

http://leh.nic.in/lahdc.htm & http://kargil.nic.in/lahdck/lahdck.htm

2. Janet Rizvi, Trans-Himalayan Caravans: Merchant Princes and Peasant Traders in Ladakh, (Oxford University Press, 2001) – is a detailed account of trade and associated material culture along the Indus and Skyok belt.

3. Page 41, Handmade In India, Editors: Aditi Ranjan, M P Ranjan, (Mapin, 2005)

The PDF version of the publication is available at: http://design-for-india.blogspot.in/2007/08/handmade-in-india-handbook-of-crafts-of.html

4. Page 41, Handmade In India, Editors: Aditi Ranjan, M P Ranjan, (Mapin, 2005)

5. Khanqah, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Khanqah

6. Abdul Ghani Sheikh, Tradition of Sufism in Ladakh, (IALS Rome, 2009)- provides a detailed account of all the different religious teachers who travelled through Ladakh and the formation of the different sects around them.

7. Zain-ul-aabedin Aabedi, Emergence of Islam in Ladakh, (Atlantic, 2009) – speaks about the different waves of Balti migration to the Indus belt south of Leh.

8. Khar-tsong-pa – or palace traders were seven Kasmiri families who were officially allowed to settle and trade solely in raw pashm (the fibre), which would be, send to Kashmir to be transformed into the exquisite Pashmia shawls.

9. Table 5: Salient features of the population groups in Ladakh, in Population Dynamics, Problems and Prospects of High Altitude Area: Ladakh – Veena Bhasin and Shampa Nag, in Anthropology: Trends and Applications, Edited by M.K. Bhasin and S.L. Malik, (Kamla Raj Enterprises, 2002)

10. Arghons: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arghons

Gerhard Emmer’s essay The Conditions of the Arghons of Leh, (IALS Leh, 2007)- elaborates on the community today.

11. André Alexander, Towards a Management Plan for the Old Town of Leh, Structuring a Plan for the Preservation of an Endangered Townscape and Revitalization of Traditional Social Structures, Berlin 2007.

http://www.tibetheritagefund.org/pages/projects/ladakh/leh-old-town.php

12. Articles by Yoginder Sikand:

http://www.countercurrents.org/comm-sikand130206.htm

http://twocircles.net/2010apr30/buddhist_muslim_relations_ladakh_part_1.html

13. Imam Khomeini Memorial Trust, Kargil : http://ikmtkargil.org/newsite/index.php

14. Jacqueline H Fewkes, Trade and contemporary society along the silk road: an ethno-history of Ladakh, London; New York: (Routledge, 2009)

15. Monisha Ahmed, Living Fabric, (Orchid Press, 2003) – looks specifically at the trade in pashmina and wool.

16. Page 46, Handmade In India, Editors: Aditi Ranjan, M P Ranjan, (Mapin, 2005)

17. Page 41, Handmade In India, Editors: Aditi Ranjan, M P Ranjan, (Mapin, 2005)

18. http://www.scribd.com/doc/20314486/belting-2005-image-medium-body-a-new-approach-to-iconology-critical-inquiry - from Image, Medium, Body – A New Approach to Iconology, Critical Inquiry Winter 2005, page 306.

19. Page 35, Handmade In India, Editors: Aditi Ranjan, M P Ranjan, (Mapin, 2005)

20. Page 42, Handmade In India, Editors: Aditi Ranjan, M P Ranjan, (Mapin, 2005)