Syncretic posters at the Sailani baba shrine in Maharashtra:

Exploring portability of religious iconography through networks of circulation

Amit Madheshiya and Shirley Abraham

INTRODUCTION

At the end of the crop gathering season in rural Maharashtra begins the season of jatras, an age-old tradition of annual religious gatherings around a shrine. Hosted by nodal villages, the religious-cultural tradition of jatras has been integral to rural Maharashtra, as these sacred sites had developed into vast communal spaces where people from various villages gathered for informal societal exchange. Catering to the host of pilgrims, the jatras have evolved to include eateries, markets selling goods of daily use, cattle fairs, and also varied means of entertainment for the diverse audience. This led to intensive communal activity around the jatra, which became a social forum even for matchmaking. It is in this tradition of annual pilgrimage to gods and deities in nearby villages that the cult of the saints and the veneration of their tombs developed in rural Maharashtra. Located in such a hectic social sphere, the interaction between the two major communities- Muslims and Hindus actively influenced each other and one of the consequences of such an influence has been ‘the accession of the Hindus to the Islamic cult of saints and to the rites of the veneration of their tombs.’1 Over the decades, the nomenclature of the urs2 was absorbed into the Marathi word jatra3, employed as a generic name for a fair in Maharashtra.

The abundance of potent places of pilgrimage in rural Maharashtra is surprising. Nearly all village residents travel to participate in a jatra, either in their own village, or in the neighboring one. This religious calendar of pilgrimage is largely Hindu, with a few Muslim saints whose tombs are venerated by pilgrims of multiple faiths.

Image 01. The dargah (shrine) of Sailani baba, in Sailani village (Buldhana district, Maharashtra) |

One of the significant Muslim saints of Maharashtra, Sailani baba, and the devotional material produced and circulated around his shrine in Sailani village (Image 01), is the focus of this exploration.

Our project focuses on how new media technologies, and through them, production of printed religious visual material contributes to this syncretism initially generated through social exchange. Further, we wish to explore how the dynamics of production and circulation of religious art permits experimentation in visual iconography, which, in turn, has created and supported new hybridity.

EARLY LIFE

Image 02. Political map of India. The state of Maharashtra is seen in western India, in light yellow. Sailani is marked in a red square in the state. |

Sailani is a remote village in the Buldhana district of Maharashtra, about 475 kilometers north east of the capital city Mumbai (Image 02). This place was an uninhabited jungle before Baba Sailani arrived here.4

Even today, Sailani village, that owes its name to the saint, is largely populated by the descendants of the first mujawir5. The village’s connectivity to the outer world depends on a lone state transport bus that plies once every day. Though every year, more than one lakh (100,000) pilgrims arrive in the village during the urs6 of the saint, celebrated in the month of March.7

Much of the religious visual media in circulation at the shrine of Sailani appears to have evolved from the oral accounts of karamaat8 available with the mujawir family, passed down to them across generations. The hagiographic literature compiled by the saint’s disciples also takes recourse in the legends narrated by the mujawir family. In the absence of any comprehensive written historical records, these oral narratives become integral in this exploration. Hagiographic tradition pays little heed to chronology and corroboration of facts, and thus we encounter varied accounts from different sources. There are two factions in the extended mujawir family narrating a slightly different account. Most of the karamaats performed by the saint are narrated unequivocally but the matters concerning Sailani’s place of residence, his last wish and last rites record dissonance in the two accounts. Understandably so, ‘as the question of sainthood was finally decided only by death, by union with the Divine Beloved; that is why tradition seldom records the date of birth of a saint, apparently because of its inherent uselessness, but always the exact date of his assumption, which becomes the cult anniversary of his urs.9 The narratives make a claim to the spiritual legacy of the saint and are thus recounted from their contextual perspectives which are mediated by the active present of the factions in mujawir family. And because it is firmly believed in popular consciousness that a saint continues to live after his death, this spiritual legacy is indeed important for the sustenance of the descendants of mujawirs.

Sheikh Husain was the principle mureed10 of saint Sailani when he arrived in this village. Sheikh Husain accompanied the saint around the village and took care of him until his death. Later, Sheikh assumed the role of the mujawir. The biography of Sailani baba that is in the popular consciousness today has been passed down generations by Sheikh Husain and other disciples of the saint.

Image 03. Front cover- Shaan e Sailani Savane Hayaat, compiled by Sheikh Afsar Sheikh Mujawar. Buldhana: 1995.

Image 03. Front cover- Shaan e Sailani Savane Hayaat, compiled by Sheikh Afsar Sheikh Mujawar. Buldhana: 1995.

|

Image 04. Back cover- Shaan-e-Sailani [The back cover mentions ‘Jamunwaale baba’. It is used to refer to Sailani baba, since he used to sit under the jamun (purple berry) tree.] |

According to available sources about Sailani baba’s life11, Kale Khan and Ameena Bi lived in Delhi in the mid 1800s. The chapbook (Image 03, 04) mentions that they enjoyed a prosperous life but had always lamented the absence of a child. One day, they hosted a fakir12 in their house. Impressed by their warmth and hospitality, he blessed them with their heart’s desire. He prophesied that the child will be a savior to many, but will leave home at the age of 12. Abdul Rehman was born to Kale Khan and Ameena Bi in Delhi in 1872. He trained to be a wrestler at home and participated in many shows, always defeating his opponents of the same age. After hearing the voice of Allah, and, as prophesied, he left home at the age of 12. He began journeying southwards in 1884. On his way, he joined an akhara13 in Balapur (a town in the Akola district of Maharashtra) and participated in various wrestling competitions. After winning one such competitive fight he was accosted by a fakir, Noor Shah who invited him for a fight. During the fight, Abdul Rehman was humbled by the old fakir and fell on his feet, asking for guidance. The fakir challenged him to wrestle for divine powers and help the poor and weak. He further sent Abdul Rehman to meet Khairuddin Muzzarat in Dharangaon Chopra in Jalgaon district. Khairuddin Muzzarat took him under his tutelage and imparted him divine knowledge. His pir14 also gave him the name Sailani, knowing that his mureed would travel far and wide and shall remain a wanderer. Sailani traveled across Maharashtra and far as Hyderabad, all this while performing karamaats. Saint Sailani belongs to the confluence of the four Sufi orders Naqshbandi, Suhrawardi, Qadiri and Chishtia. He patronized fourteen khalıfas15 who are spread across Maharashtra propagating the spiritual lineage. During his wanderings he came to Pimpalgaon Sarai village where he met Sheikh Husain, his first mureed. Sailani baba died here in 190716. From the following year, people began gathering at his urs celebrations.17

SAINTHOOD AND MIRACLES

Iranian Sufi of the ninth century, At-Tirmidhi, was the first to have written about the concepts of Sainthood.18 ‘He advanced the theory that the Sufi adept was a saint who, by his spiritual achievements upheld the order of the Universe. Standing in the hierarchy of God’s emanation, he was capable of miraculous deeds. At-Tirmidhi’s doctrine of sainthood became an almost universal belief in saints as intercessors with God, and of a veneration of saints and their descendants, disciples, and tombs as repositories of the divine presence.’19 At-Tirmidhi wrote: ‘The occurrence of miracles inspires in others, the belief in the genuineness of the sainthood…The miracle is both the proof of this genuineness and its result, for it is the saint’s genuineness that enables him to work miracles.’20

In the pilgrim’s consciousness, a karamaat constitutes the most important event in the biography of a saint and is remembered in great detail. It is quickly picked up by popular lore, and in every recounting, assumes a new dimension. The cult of Sufi saints is determined by such legends to a great extent, fables and myths which cyclically evolve around shrines and places of burial. Observes Anna Suvorova, that, ‘These miracles include levitating, walking on water, invoking elemental phenomena (rain, drought, earthquake, etc.), and traversing vast distances in a moment, friendship with wild beasts, clairvoyance, and thought-reading at a distance. Sufi hagiographers have combined all these miracles in twelve categories, among which resurrection of the dead (ihya al-mawat) was of the utmost importance.’ (Suvorova 2004: 14)

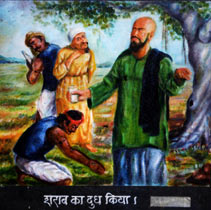

Image 05. ‘Sharaab ka doodh kiya’- Converted alcohol into milk. |

According to the present family of the Mujawirs (as also mentioned in the chapbook about Sailani’s life),21 the resurrection of a dead dog was the first miracle performed by Sailani. This was followed by the etiologic miracle about the origin of a reservoir, stalling rains, transforming alcohol into milk (Image 05) , walking on water, exorcising evil spirits, burning lamps with water, simultaneous presence at two places, friendship with beasts, clairvoyance and substitute for pilgrimage to Mecca for a person in need.

Many such miracles, flowing from the hagiographic tradition and often even amalgamating with the miracles ascribed to other saints have found repose in the popular lore of the cult of saint Sailani.

It is clear that these miracles depict the Saint’s power to control, alter and transform the forces and processes of nature. According to Samuel Landell Mills, such routine and miraculous attributions of saintly identity, are ‘characteristic of south Asian Sufi saints…they connect the living and the dead, the seen and the unseen, the divine and the mundane, the locality and the wider world, the real and the ideal.’22 This is makes them ‘an epiphany, a manifestation of the divine being and the vehicle of communication between man and God’ 23 and inspires belief in the divine powers that the saint stands for. ‘Devotees believe that the spiritual mastery achieved by the pir irradiates his body with blessedness, and that this spreads to the persons and objects with which he comes in contact. These objects extend the physical presence of the pir, and provide solid matter for the construction of his sanctity. The devotional imaginings of a pir’s capacity to animate otherwise inert objects, often marginalized as a peripheral ramification of his spiritual power, is the crux of his ‘saintly’ performance. And these saintly vehicles are anthropomorphised, they are attributed with almost human capacities to interact.’ 24

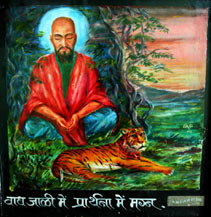

Image 06. ‘Sailani baba sher ko chai pilaate they’- Sailani baba made lions drink tea. |

Like many other saints, Sailani is believed to have spent most of his life wandering through the forests, and so his relationship with animals is the natural subject of many a folk tale. Wild beasts, supposed to be an obvious part of his spaces of habitation in the jungle are prominent in oral accounts as well as visual depictions. One of the popular legends surrounding Sailani baba’s association with animals is that of taming a tiger25 and offering him tea. (Image 06) It is believed that Sailani was once roaming around the jungles in the Khor village in Buldhana district. Sailani performed namaz in the evening and was teaching his disciples. One of his mureeds started making tea. As soon as everyone poured tea in their saucers, they heard the roar of a tiger. The disciples were afraid and started scrambling for a place to hide. Sailani calmed his disciples saying ‘He is also Allah’s makhlooq (creation) and was tempted to drink tea with us.’ Following this, he invited the tiger to sit near him and poured tea. After the tiger drank tea, Sailani instructed him to go back to the jungle. The tiger promptly obeyed Sailani.

Image 07. ‘Baagh jaali mein prarthana mein magan’- Engaged in devotion near the baagh jaali- the web of the tigers. |

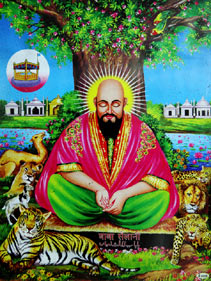

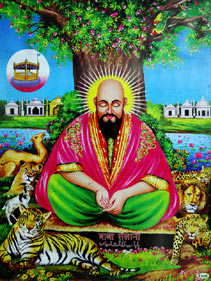

It is notable that the oral accounts about Sailani baba and his relationship with animals start with this miracle, and then move on to his friendship with them, establishing a sense of harmony between him and the beasts. So, while Sailani is believed to have exercised command over wild animals, notably, his relationship with them is defined by taming them, through compassion and friendship, and not forced control, or combat. Additionally, involving a ferocious beast in a rather-everyday, human act, like drinking tea makes the Saint’s personality more accessible and appealing. It is believed that lions and tigers used to clean his place of worship, with their tails. He is also supposed to have cured injured wild animals with remains of ash obtained from fire after burning wood. In visual representations of Sailani baba, the iconography of wild animals, mainly tigers and lions, is significant. They are seen flanking him in most of the visual iconography around him. It alludes to the myths associated with him, and fires the believers’ imagination about his immensely miraculous powers. (Image 07, 08, 09, 10)

Image 08. ‘ Baba Sailani’ |

Image 09. Sailani baba in the company of wild animals in the forest. |

Image 10. ‘Mujawar ke khet mein baba’- The baba in the Mujawar’s fields. |

Image 11. Haji Bektash. (image sourced from the internet - http://bit.ly/1bOdW8U) |

In popular visual culture, the iconography of animals is a universal theme with depiction of many saints all over the world. It implies that the saint has achieved restraint over himself, conquered his own being and so is able to extend that sense of discipline and command to animals. ‘A Sufi saint is supposed to have overcome the bodily and animal forces within him, restore purity of will and intellect, and thus realise his divine nature.’26 Among the other saints who have been depicted with animals include Haji Bektash (Image 11), a 13th century Iranian saint,27 the headquarters of whose order were later moved to Albania and remain there until date. He is a renowned figure in the history and culture of the Ottoman Empire and modern day Turkey. There are many myths surrounding his relationship with animals, namely one of bringing a cooked fish to life, from its unbroken bones.28 He is also depicted in a posture of kindness, embracing animals. This is one example of how such imagery of benevolence towards animals unites the saints across a transcultural imaginational.

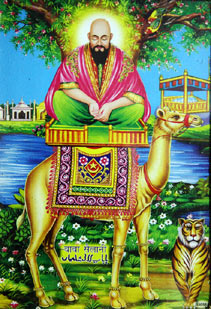

Image 12. Sailani baba depicted seated atop a camel. |

Apart from wild beasts, the other animal which Sailani is usually portrayed with, is the domesticated camel (Image 12). Though oral accounts deny any direct interaction of Sailani with a camel in the past, the offering of sandalwood on the main day of the urs is carried on camelback. On being asked the reason, and whether the animal is believed to have a connection with the saint, the mujawirs present a rather practical, utilitarian answer. The choice of the camel is attributed to its height, which makes the offering inaccessible to any disturbance from the lakhs of pilgrims which gather there. They believe that the offering was always traditionally carried on camelback here. (Any potential difficulty in sourcing a camel in this region has been avoided by the domestication of a camel by the mujawir families.)

This depiction with animals incorporates Sailani into a recognised and easily identifiable iconography. This lifts the saint from his localised presence into a national one, and even exposes him into the global iconography. Integration of Sailani baba with well-known symbols, displays an attempt by the publishing industry to ensure maximum familiarity and connect of local saints with previously established and widely revered imagery. The universality of these images draws pilgrims to Sufi shrines everywhere into a common vision of, and association with, the divine.

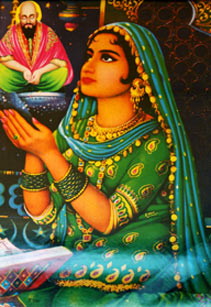

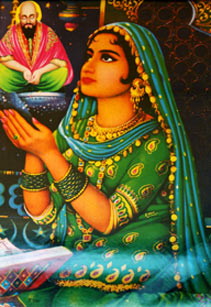

Image 25. Sailani baba with a typical image of Muslim piety- a woman dressed in make up and jewelery, raising her hands in a gesture of supplication. The figure of Sailani baba has been inserted in the direction of her hands, uplifting him to the status of the power she is praying to. |

All the previous images are familiar icons in Islamic iconography, and are often seen hanging in homes. It is notable that, by affixing a sticker of Sailani baba, an established image, an existing reference has been appropriated within the cult of Sailani. The sticker is also borrowed from the popular representation of Sailani baba, and is standardized across such posters. Despite employing the same image of baba in every poster, it still makes him a participant in the varied scenes which have been revered for long, not merely as a benign observer of the proceedings, but sometimes even becoming the focal point of the image. In the image above (Image 25), where the devotee has conventionally been seen praying to an invisible power, the sticker appears to suddenly provide a physical form to the power. Sailani baba is instantly integrated into the widespread imagery seen across shrines all over the country, and effortlessly branded as a popular saint. Thus, this technique opens up an imaginary transnational landscape of devotion, finding form in such posters. (Image 26). In the case above, it pushes the dynamics of an image which have been ingrained in the memory of the pilgrim, with the assimilation of a saint in the frame.

Image 26. A woman pays homage to the shrine of Saint Abdul Qadir Jilani in Baghdad (Iraq) who is considered in high esteem by all Sufis in South Asia. The saint’s miracle (of saving a drowning boat) is depicted in the backdrop. Sailani baba has been inserted onto the scene. Framed poster being sold in a shop near Sailani shrine. |

This production technique is quick and effective, since it employs a ‘standardised image.’ ‘Standardized images are authoritative, when displayed, they seem to have the function of ‘authenticating the ‘real’ three dimensional icons within.’39 This also finds an explanation in the economics of the poster-producing industry. Shabbir Ahmed, a digital poster maker in Chikhli (a small town located 20 kilometers away from Sailani), confesses that due to the smaller market in Sailani, as compared to the bigger saints of the order, a generic image of Sailani Baba is often used across the board. The publishers did not invest into a new design, rather, they appropriated the existing posters by sticking an image of Sailani Baba and further mass produced it. This did not only co-opt the existing popular visual culture but also led to its homogenization on a pan-Indian scale.

Image 27. An imaginary gathering of four saints. Sailani Baba seen with Gajanan Maharaj of Shegaon (seen in red robe on the left), Waris Shah (in green robe, center) and Sai Baba (in white robe). The image of Sailani Baba has been superimposed on this popular poster. |

Looking at the posters, it is interesting to note that no attempt has been made by the artist to conceal the cut-and-paste job. It reminds us of the pre image editing software era when such pictorial edits were done manually. One of the most remarkable edit is the one in which we see Sailani along with other popular saints- Gajanan Maharaj of Shegaon, the Chishti saint Waris Shah, and Sai Baba of Shirdi (Image 27).

Jürgen Frembgen refers to such an imaginary meeting of the most revered saints of the region, as ‘the timeless conclave’40 , since the saints who depicted in this meeting often lived in different times. In the poster above, Gajanan Maharaj (first appeared on February 23, 1878, seen until September 08, 1910), Waris Shah (1809-1905) and Sai Baba (September 28, 1838 – October 15, 1918) are seen here with Sailani Baba (1872-1907). In the case above, a meeting seems plausible but there is no historical record of the same. Similar posters are sold around numerous shrines and the concept of this ‘timeless conclave’ is like a template which finds various regional Saints occupying it, depending upon region. This is also known as mehfil-e-auliya (assembly of saints) or darbar-e-auliya (royal court of saints) and this poster one of the most popular among the pilgrims. Sheikh Hashim Mujawar41 considers such posters as khayali- purely imaginative and believes that they have no basis for existence but are inspired by the faith of the people.

Image 28. Sailani baba painted over plants, rivers and animals. This painting attempts to illustrate that Sailani baba continues to live in, and act through them. |

Image 29. Framed poster with an image of Sailani superimposed on the shrine. The image attempts to illustrate that the Saint lives on in his shrine. |

Arguably, the ‘popularization of the cult of saints was facilitated by the belief that baraka, divine bliss, did not just abide in a saint; it could travel from him to ordinary people. Baraka did not disappear after a saint’s death, but in a reinforced form continued to emanate from his tomb, from things belonging to him and even from his name.’42 (Image 28, 29)

Most of the pilgrims to the saint’s tombs seek his baraka and believe that ‘through it he brings to those who worship him, prosperity, happiness, all the good things of this world; he can bestow his gifts, passing beyond the individual, upon a whole district, and even beyond the confines of this world, through his powers of intercession with Allah.’43 Indeed the same baraka is believed to emanate from the souvenirs that the pilgrims buy at the shrine including the posters. Realising this, the religious image producing industry alludes to the most familiar and the holiest icons in Islam. Packing a lot in one image, it makes it difficult for the pilgrims to overlook this imaginatively juxtaposed colloquy of saints.

Image 30. Sailani Baba is portrayed sitting in the company of five celebrated sufi mystics and their shrines (clockwise from bottom left): Baba Farid, Khwaja Qutbuddin Bakhtiyar, Khwaja Moinuddin Chishti, Hazrat Ghuas-e Azam, Hazrat Bu Ali Sharif, and Hazrat Nizamuddin Aulia. Also visible are the shrines of Mecca and Medina on the top. |

Image 31. Seen here is a poster assembled in the Sailani museum. It shows Sailani baba with other a few saints and holy men - Hazrat Khairu Shah baba, Hazrat Iman Shah baba, Hazrat Mohammad Shah Baba, Hazrat Sayyed Khairu Shah Baba, Hazrat Naseeb Shah Baba, Kol gaon wale Baba, Sayyed Ali Shah, Hazrat Khairuddin Shah Auliya. The Saints are not so popular and recognized in visual iconography, but here, the familiar figure of Sailani baba makes this an instantly identifiable poster. |

Sheikh Hashim Mujawar’s claim of trio posters being inspired by the faith of the people rings true, since many pilgrims show an inclination to buy framed posters of many saints in the same frame. This practice was probably popularised because this inventive production makes complete economic sense even for the pilgrims; people of various faiths who come to Sailani shrine can carry back just one souvenir that depicts some of the most revered saints that they worship. On being asked about the significance of this poster in everyday life, they confessed to believing that there is more baraka- prosperity, in the presence of a greater number of saints. On being encouraged to also reflect upon how it impacts the community, beyond personal and familial concerns, the pilgrims thought that the poster cements the solidarity between the followers of these saints. Thus, the popularity of this poster demonstrates the bond of the mureeds with their pirs and also serves to consolidate the charisma of the saints. In some images, Sailani is placed with the greatest amongst the cult of saints, Hazrat Ghuas-e Azam, Hazrat Bu Ali Sharf, Khwaja Qutbuddin Bakhtiyar, Hazrat Nizamuddin Aulia and Khwaja Moinuddin Chishti – who lived in a different chronology of time from Sailani (Image 30, 31). But in the quest to produce cheaper and recognisable posters, the industry co-opts the popular representations, modifies and mass produces it leading to the homogenization of the Muslim religious imagery on a pan-Indian scale.

Image 32. Sailani baba superimposed on an image of Lord Shiva. |

Simultaneously, this industry also introduces something unique to this production, a syncretic element in the representation of the Muslim saints. ‘Interestingly, the artists, manufacturers, and sellers of these images are not necessarily all Muslim. The publishers are often those entrepreneurs who deal with posters of any religion, irrespective of their own faith…Whether it is a Hindu artist drawing a Muslim theme, or vice versa, does not seem to bar him from expressing the characteristic pathos and devotion particular to the image. In the entire process of image manufacture, no one, including the commissioning person, artist, painter, or distributor, seems to bother about which religion they cater to, as long their product augments their client’s devotion and their client’s spending power. But in the process, they do seem to transplant the icons, symbols, and myths across the borders of faith, making these images so unique to their subject.’44 In a distinctive image, Sailani is superimposed over the lingam45 of Lord Shiva (Image 32)

Image 33. Sailani baba superimposed on an image of Lord Shiva. |

The paraphernalia that surrounds him- castor lamp, incense sticks, conch, flowers and the plate of offering is typical of the Hindu rituals. Sitting under the perennial flow of the holy milk, flanked by the divine snake, Sailani is now sitting against Shiva’s trident. The majestic mount Kailash is seen in the background and the Hindu holy symbol Om is written with a halo. Even in this unmistakable Hindu mythological scene one can notice the presence of a pair of roses, (Image 33) distinctly associated with the cult of the saints, over the Shiva lingam in the original image.

As against images of Islamic posters, where Sailani baba is seen juxtaposed with other saints, here, he is seen occupying the seat of Shiva, by replacing the Hindu deity. In this rare image, the benevolent figure of Sailani baba sits meditating amongst the symbols which define Shiva. Such a composite image, is intended to be greater than the sum of its parts- the painting is clearly meant to stoke the imagination of Hindu pilgrims and encourage them into the Sufi cult of Sailani baba.

The syncretic ethos of such popular images is witness to the cult of saints as a living heritage of the ‘composite’ culture of South Asia, common to India, Pakistan and Bangladesh.46

Image 25. Sailani baba with a typical image of Muslim piety- a woman dressed in make up and jewelery, raising her hands in a gesture of supplication. The figure of Sailani baba has been inserted in the direction of her hands, uplifting him to the status of the power she is praying to. |

All the previous images are familiar icons in Islamic iconography, and are often seen hanging in homes. It is notable that, by affixing a sticker of Sailani baba, an established image, an existing reference has been appropriated within the cult of Sailani. The sticker is also borrowed from the popular representation of Sailani baba, and is standardized across such posters. Despite employing the same image of baba in every poster, it still makes him a participant in the varied scenes which have been revered for long, not merely as a benign observer of the proceedings, but sometimes even becoming the focal point of the image. In the image above (Image 25), where the devotee has conventionally been seen praying to an invisible power, the sticker appears to suddenly provide a physical form to the power. Sailani baba is instantly integrated into the widespread imagery seen across shrines all over the country, and effortlessly branded as a popular saint. Thus, this technique opens up an imaginary transnational landscape of devotion, finding form in such posters. (Image 26). In the case above, it pushes the dynamics of an image which have been ingrained in the memory of the pilgrim, with the assimilation of a saint in the frame.

Image 26. A woman pays homage to the shrine of Saint Abdul Qadir Jilani in Baghdad (Iraq) who is considered in high esteem by all Sufis in South Asia. The saint’s miracle (of saving a drowning boat) is depicted in the backdrop. Sailani baba has been inserted onto the scene. Framed poster being sold in a shop near Sailani shrine. |

This production technique is quick and effective, since it employs a ‘standardised image.’ ‘Standardized images are authoritative, when displayed, they seem to have the function of ‘authenticating the ‘real’ three dimensional icons within.’39 This also finds an explanation in the economics of the poster-producing industry. Shabbir Ahmed, a digital poster maker in Chikhli (a small town located 20 kilometers away from Sailani), confesses that due to the smaller market in Sailani, as compared to the bigger saints of the order, a generic image of Sailani Baba is often used across the board. The publishers did not invest into a new design, rather, they appropriated the existing posters by sticking an image of Sailani Baba and further mass produced it. This did not only co-opt the existing popular visual culture but also led to its homogenization on a pan-Indian scale.

Image 27. An imaginary gathering of four saints. Sailani Baba seen with Gajanan Maharaj of Shegaon (seen in red robe on the left), Waris Shah (in green robe, center) and Sai Baba (in white robe). The image of Sailani Baba has been superimposed on this popular poster. |

Looking at the posters, it is interesting to note that no attempt has been made by the artist to conceal the cut-and-paste job. It reminds us of the pre image editing software era when such pictorial edits were done manually. One of the most remarkable edit is the one in which we see Sailani along with other popular saints- Gajanan Maharaj of Shegaon, the Chishti saint Waris Shah, and Sai Baba of Shirdi (Image 27).

Jürgen Frembgen refers to such an imaginary meeting of the most revered saints of the region, as ‘the timeless conclave’40 , since the saints who depicted in this meeting often lived in different times. In the poster above, Gajanan Maharaj (first appeared on February 23, 1878, seen until September 08, 1910), Waris Shah (1809-1905) and Sai Baba (September 28, 1838 – October 15, 1918) are seen here with Sailani Baba (1872-1907). In the case above, a meeting seems plausible but there is no historical record of the same. Similar posters are sold around numerous shrines and the concept of this ‘timeless conclave’ is like a template which finds various regional Saints occupying it, depending upon region. This is also known as mehfil-e-auliya (assembly of saints) or darbar-e-auliya (royal court of saints) and this poster one of the most popular among the pilgrims. Sheikh Hashim Mujawar41 considers such posters as khayali- purely imaginative and believes that they have no basis for existence but are inspired by the faith of the people.

Image 28. Sailani baba painted over plants, rivers and animals. This painting attempts to illustrate that Sailani baba continues to live in, and act through them. |

Image 29. Framed poster with an image of Sailani superimposed on the shrine. The image attempts to illustrate that the Saint lives on in his shrine. |

Arguably, the ‘popularization of the cult of saints was facilitated by the belief that baraka, divine bliss, did not just abide in a saint; it could travel from him to ordinary people. Baraka did not disappear after a saint’s death, but in a reinforced form continued to emanate from his tomb, from things belonging to him and even from his name.’42 (Image 28, 29)

Most of the pilgrims to the saint’s tombs seek his baraka and believe that ‘through it he brings to those who worship him, prosperity, happiness, all the good things of this world; he can bestow his gifts, passing beyond the individual, upon a whole district, and even beyond the confines of this world, through his powers of intercession with Allah.’43 Indeed the same baraka is believed to emanate from the souvenirs that the pilgrims buy at the shrine including the posters. Realising this, the religious image producing industry alludes to the most familiar and the holiest icons in Islam. Packing a lot in one image, it makes it difficult for the pilgrims to overlook this imaginatively juxtaposed colloquy of saints.

Image 30. Sailani Baba is portrayed sitting in the company of five celebrated sufi mystics and their shrines (clockwise from bottom left): Baba Farid, Khwaja Qutbuddin Bakhtiyar, Khwaja Moinuddin Chishti, Hazrat Ghuas-e Azam, Hazrat Bu Ali Sharif, and Hazrat Nizamuddin Aulia. Also visible are the shrines of Mecca and Medina on the top. |

Image 31. Seen here is a poster assembled in the Sailani museum. It shows Sailani baba with other a few saints and holy men - Hazrat Khairu Shah baba, Hazrat Iman Shah baba, Hazrat Mohammad Shah Baba, Hazrat Sayyed Khairu Shah Baba, Hazrat Naseeb Shah Baba, Kol gaon wale Baba, Sayyed Ali Shah, Hazrat Khairuddin Shah Auliya. The Saints are not so popular and recognized in visual iconography, but here, the familiar figure of Sailani baba makes this an instantly identifiable poster. |

Sheikh Hashim Mujawar’s claim of trio posters being inspired by the faith of the people rings true, since many pilgrims show an inclination to buy framed posters of many saints in the same frame. This practice was probably popularised because this inventive production makes complete economic sense even for the pilgrims; people of various faiths who come to Sailani shrine can carry back just one souvenir that depicts some of the most revered saints that they worship. On being asked about the significance of this poster in everyday life, they confessed to believing that there is more baraka- prosperity, in the presence of a greater number of saints. On being encouraged to also reflect upon how it impacts the community, beyond personal and familial concerns, the pilgrims thought that the poster cements the solidarity between the followers of these saints. Thus, the popularity of this poster demonstrates the bond of the mureeds with their pirs and also serves to consolidate the charisma of the saints. In some images, Sailani is placed with the greatest amongst the cult of saints, Hazrat Ghuas-e Azam, Hazrat Bu Ali Sharf, Khwaja Qutbuddin Bakhtiyar, Hazrat Nizamuddin Aulia and Khwaja Moinuddin Chishti – who lived in a different chronology of time from Sailani (Image 30, 31). But in the quest to produce cheaper and recognisable posters, the industry co-opts the popular representations, modifies and mass produces it leading to the homogenization of the Muslim religious imagery on a pan-Indian scale.

Image 32. Sailani baba superimposed on an image of Lord Shiva. |

Simultaneously, this industry also introduces something unique to this production, a syncretic element in the representation of the Muslim saints. ‘Interestingly, the artists, manufacturers, and sellers of these images are not necessarily all Muslim. The publishers are often those entrepreneurs who deal with posters of any religion, irrespective of their own faith…Whether it is a Hindu artist drawing a Muslim theme, or vice versa, does not seem to bar him from expressing the characteristic pathos and devotion particular to the image. In the entire process of image manufacture, no one, including the commissioning person, artist, painter, or distributor, seems to bother about which religion they cater to, as long their product augments their client’s devotion and their client’s spending power. But in the process, they do seem to transplant the icons, symbols, and myths across the borders of faith, making these images so unique to their subject.’44 In a distinctive image, Sailani is superimposed over the lingam45 of Lord Shiva (Image 32)

Image 33. Sailani baba superimposed on an image of Lord Shiva. |

The paraphernalia that surrounds him- castor lamp, incense sticks, conch, flowers and the plate of offering is typical of the Hindu rituals. Sitting under the perennial flow of the holy milk, flanked by the divine snake, Sailani is now sitting against Shiva’s trident. The majestic mount Kailash is seen in the background and the Hindu holy symbol Om is written with a halo. Even in this unmistakable Hindu mythological scene one can notice the presence of a pair of roses, (Image 33) distinctly associated with the cult of the saints, over the Shiva lingam in the original image.

As against images of Islamic posters, where Sailani baba is seen juxtaposed with other saints, here, he is seen occupying the seat of Shiva, by replacing the Hindu deity. In this rare image, the benevolent figure of Sailani baba sits meditating amongst the symbols which define Shiva. Such a composite image, is intended to be greater than the sum of its parts- the painting is clearly meant to stoke the imagination of Hindu pilgrims and encourage them into the Sufi cult of Sailani baba.

The syncretic ethos of such popular images is witness to the cult of saints as a living heritage of the ‘composite’ culture of South Asia, common to India, Pakistan and Bangladesh.46

TRANSLATING THE ‘ORIGINAL’ IMAGE

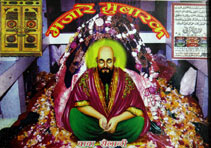

Image 34. Popular, current day representation of Sailani baba. |

What is intriguing about the representation of Sailani in the popular religious posters is the use of a single image of the saint across the board. In this template image, Sailani is sitting in a meditative posture, his eyes are closed and there is a halo around him. A decorative pink shawl is draped around his shoulders, almost looking like a flowing robe, and he wears a green loincloth. It appears that the use of this image of Sailani in each and every representation, even from different publishers, is an attempt to stay true to a photograph that is believed to be of Sailani baba. The mujawir family claims that the photograph was made in 1902 by a stray traveler and the one in the possession of Sheikh Rehman Mujawar is indeed the ‘original’ image. In this black and white photograph, the saint appears to be in meditation and is looking down, a cloth hangs loose at his shoulders and the thumbs of his hands are joined over his crossed legs (Image 34).

However, ‘Images tent to be recycled within lineages, and when this is combined with the enormous reproductive power of photo offset printing, the consequences can be startling.’47 This is apparent when we examine the present day printed avatar of saint Sailani.

Image 35 . A black and white image of Sailani baba, often claimed to be an ‘original’ photograph of the saint. |

It is a close imitation of a black and white photograph of Sailani baba, often claimed as an ‘original’ image (Image 35) of him , albeit in colour and devoid of the solemnity of the brooding figure in the former image. The black and white photograph of Sailani serves as a generic template on which different additions are made. Additions like the gilded embroidery are achieved to make the poster more attractive and could also be attributed to the artists’ attempt in depicting the rutba, or eminent position of the saint.

The ‘original’ photograph, has been identified in the popular consciousness and to a great extent, helped spread the cult of saint Sailani. It is displayed prominently at the Aashiyana hotel owned by the mujawirs, and is an attraction for pilgrims. But unlike the photographs of other saints like Waris Ali Shah and Sai baba the photograph of Sailani baba never actually got iconized as such. What floods the markets today are not the copies of the black and white photograph, but the colourful imitations embellished by artists. This shift is interesting to note as veneration of a saint is almost always the veneration of his tomb along with some material evidence of his temporal life like dress, turban, sandals, utensils etc.48 and in this tradition, an original photograph should be an indispensible relic emitting the saint’s baraka. And while theophany is associated even with god-posters, (supposedly the reproductions or real images) where they are supposed to function as the ‘real’ image, why is the ‘original’ image, overlooked in visual depiction on a mass scale?

Could it be attributed to its authenticity being in question or, instead, that a colorful imitation is more amenable to a common pilgrim? Sheikh Hashim Mujawir who is currently the principal caretaker at Sailani’s shrine discredits this lone photograph of the saint, claiming it as a fake. He argues that there are certain discrepancies in the photograph that scream hoarse about its dubious credentials. If the photograph was made in 1902, as claimed by the other faction of the Mujawir family then Sailani should have been thirty years old when photographed, though he looks much older. Sheikh Hashim reminds us that when Sailani died in 1907, he was thirty five years old, so even if the photograph was made at a later date he could not have appeared so aged. He adds that the fingers of Baba, in the photograph, do not seem natural rather appear crafted. Hence extrapolating that it is not a photograph altogether. Though Hashim Mujawar also reluctantly adds that there indeed was a photograph of Sailani made a few years before the saint died. In that photograph, Sheikh Hashim informs, Sailani was sitting with a group of his khalifas. A painter could have singled out Sailani from this photograph and reproduced it in the form that is now claimed as the ‘original’, he further adds. It is commonly believed by the skeptics that over the years, the robe worn by Sailani in the black and white photograph was mistaken for a beard by some artist and this is how Sailani, who only had a stubble, came to acquire a flowing beard in his printed avatar. Khairu Shah Baba of Chikhli, one of Sailani Baba’s prominent disciples had requested for the ‘original’ photograph (original, as indicated by Sheikh Hashim). Pleading to Sheikh Hashim’s grandfather, Khairu Shah Baba had said “you have the real Sailani baba, why do you need a chhalawa?”49

THE ELEMENT OF PERFORMANCE:

In the decades following the death of Sailani in 1907, as photography became more affordable and popular amongst the masses it was also gradually assimilated in the cult of Sailani baba. A travelling studio began visiting the urs, dishing out souvenirs for pilgrims to carry back home in the form of photographs.

Image 36 . Studio backdrop of Sailani baba. |

Bringing a performative facet to the partaking of baraka of the saint, the studio enabled the pilgrims in getting their photographs made along with a life size cut-out of Sailani baba placed against verdant slopes painted on a cloth backdrop (Image 36). For years, the cut-out bears the same template image of the saint that the poster-making industry had standardized.

The image of Sailani baba is often juxtaposed against backdrops like pastoral landscapes or mosques. Apart from offering the possibility of selecting backgrounds, the studio also stocks movable cut outs of lions and camels handy for the pilgrims to chose from, icons popularly associated with Sailani baba. The depiction of this scene borrows from the popular visual culture spawned around the cult of Sailani. This exhibit is often created with subjective perspective on size and scale, highlighting chosen aspects, like the figure of Sailani baba looming larger than the mosque in the background. Sometimes all the participating elements are painted upon a continuous surface. Such attributes take them into the tradition of the diorama.

Image 37. Popular gestures of Muslim piety find their way into image making practices in photo studios. |

Image 38. Popular gestures of Muslim piety find their way into image making practices in photo studios. |

Pilgrims get themselves photographed along with these backdrops and mages, interestingly, in gestures that they have consumed from the religious popular imagery available in the markets of urs. Gestures of supplication, worship, being blessed and shepherded typical to be found on calendars, posters etc. representing the popular Muslim piety (Image 37, 38).

It is in this potent space of image making, that one becomes a part of the image that one has been consuming all the while. In homes, such photos are revered and cherished just as the other holy tokens carried back from the site, assuming a place beside other posters and framed images.

CONCLUSION:

Image 39. A sticker of Sailani baba affxed to a poster with a moral lesson. |

Through the course of our field work, we encountered Sailani baba and his most familiar animal iconography, the tigers, in a striking juxtaposition. A sticker of Sailani baba affixed to a poster with a moral lesson ‘Love one another and you will be happy’ (Image 39), interestingly, also employing the visual of two majestic tigers. The three elements of the hybridised image would, usually, work independent of each other, or possibly as a combination of two. However, in an imaginative juxtaposition, insertion of the Sailani baba sticker has, at once, appropriated a non religious, somewhat mundane, yet familiar iconography of everydayness of the poster into the saint’s fold. This creation of meaning through a poster with tigers is an ingenious one. Unlike other posters where the tigers (both through positioning and size) seem to be subservient to the saint, sitting by his side, mostly under a tree, amalgamated into the ‘religious’ setting, here they are seen fairly independent of him, but their religious connection with Sailani is instantaneous. (Image 40) Thus, a sticker of Sailani baba works not only to create syncretic images across religions, but also creates a new kind of iconic commentary of hybridity between the religious and the mundane (Image 41).

Image 40. A sticker of Sailani baba affxed to a poster with a moral lesson. |

According to H Daniel Smith, ‘the genre of religious art has been the source of religious innovations that enrich the variety of ways in which tradition can be expressed. Poster artists, for example, have portrayed well known deities in new combinations. The relative fluidity of this medium seems to permit an unprecedented degree of iconic experimentation. The same fluidity is even more marked in the combinations and permutations of deity posters found in domestic shrines and other micro settings. Here, iconic symbolism responds directly to the religious imaginations of individuals and the result is a pattern in which the sub continental traditions, reflected in standard images, can be manifested in endlessly local ways.’

|

|

As is evident through the essay, standardized images are often combined in permutations that reflect the beliefs and consequently formed rituals of families and individuals. Lawrence Babb sums up the phenomenon: ‘It can be argued that, therefore, popular religious art has not only fostered certain universalizing trends, but has also enhanced and diversified the total range of meanings that has been expressed through iconic imagery.’50

The visual culture around the Sailani baba shrine stands testimony to how the adaptability of printed religious material facilitates imaginative devotional landscapes and religious practices. This underscores the potential of popular art to support religious variety. Innovative image making practices have launched a local saint like Sailani baba into the repertoire of global iconography. This helps to popularize and sustain the cult of the saint, by generating and supporting a new syncretism, circulating a topography of transnational and transcultural devotion.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Babb, Lawrence A. and Wadley, Susan S. (Ed.) Images in Media and Transformation of Religion in south Asia. University of Pennsylvania Press: 1995.

Gaudefroy, Demombynes. Muslim Institutions. Seattle: Whitaker Press: 2007.

Lapidus, Ira Marvin. A History of Islamic Societies. Cambridge University Press: 2002.

Saeed, Yousuf. “An Image Bazaar for the Devotee” In ISIM Review 17: 2006. (International Institute for the Study of Islam and Modernity, Leiden The Netherlands)

Suvorova, Anna. Muslim Saints of South Asia The eleventh to Fifteenth Century. London: RoutledgeCurzon: 2004.

van Bruinessen, Martin, ‘Haji Bektash Sultan Sahak, Shah Mina Sahib and Various Avatars of a Running Wall.’ sourced from http://www.let.uu.nl/~martin.vanbruinessen/personal/publications/Bruinessen_Cansiz_duvar.pdf

(This is an updated version of an article that first appeared in Turcica XXI-XXIII: 1991: 55-69.)

Werber, Pnina and Base, Helene. (Ed.) Modernity, locality and the performance of emotion of Sufi cults London: Routledge: 1998.

Other sources:

Roy Burman, J J. Hindu Muslim Syncretic Shrines and Communities. New Delhi: Mittal Publication: 2002.

Narratives of Sheikh Hashim Mujawar and Sheikh Rehman Mujawar.

References from Shaan-E-Sailani Savane hayaat, compiled by Sheikh Afsar Sheikh Mujawar. Buldhana: 1995.

Interviews with pilgrims visiting Sailani.

Interviews with digital poster makers in Chikhli.