Replicating Memory, Creating Images:

Pirs and Dargahs in Popular Art and Media of Contemporary East Punjab

Yogesh Snehi

Introduction

Pirs and dargahs constitute an important feature of the popular tradition of saint veneration in medieval and modern Punjab. Before the British arrived in India, networks of shrines loosely linked within the Sufi orders of major silsilas spread through much of the province as the descendants and successors (khalifas) of many of the major saints established their own khanqahs (hospice). There was also a tradition of constructing ‘lesser shrines’ dedicated to one or many, major or minor Sufi centres of medieval Punjab.1 The networks were particularly dense in parts of the Indus valley; for instance in South-Western Punjab the shrines of the descendants of Syed Jalaluddin Bukhari of Uch dotted the countryside when the British arrived.2

These shrines represented sources of power (barkat) to the common people and were open to people from all religious persuasions. Liebeskind terms this all-inclusive approach as the local face of Islam.3 There was yet another practise of constructing ‘memorial shrines’ which gradually developed into distinctive centres of cultural practices, often denoting local as well as long term geographical influences. These memorial shrines existed in the realm of the popular and inspired many folk writer of medieval and modern Punjab evolving into a distinct form of ‘saint worship’. 4

Significantly, these popular shrines emerged as centres for inter-communal dialogue and evolved into a distinct form of cultural practice of saint veneration. One particularly distinct character of this social formation was that while Western Punjab (now in Pakistan) became a major centre of emergence and dissemination of Sufism in the medieval period, it was eastern Punjab (India) which was the recipient of the vast influence of sacred shrines in Sind, Multan, Bahawalpur and Montgomery districts of the colonial India. This paper entailed an extensive survey of popular Sufi shrines through an overview of two trajectories of contemporary Punjab. Firstly, it highlights the landscape of various old and new popular Sufi shrines in contemporary Punjab and secondly, it reflects upon the continued significance of popular Sufi traditions among various classes and ethnic communities of Punjab, delineating a unique picture of social formation of the region.5

The significance of this social formation lies in the fact that when the province of Punjab was partitioned in 1947, it transformed the demography of the region in such a way that east and west Punjab became Sikh/Hindu and Muslim dominated regions respectively. Both these regions had their significant share of major and local Sufi shrines which would thereafter become inaccessible to each other.6 Over the years the memories of shared past were reconfigured in new spaces and either new memorial shrines were created or the older ones restructured with new sets of functionaries and sajjada nishins. This reconfiguration of space, accessibility to shrine and Pirs associated with them will be significantly mediated through circulation of images which would in a way replicate the shared memories of the pre-partitioned Punjab. It needs to be underlined that saint veneration continues to be a significant articulation of pre-partition memories of shared popular traditions.7

This study was executed through an extensive survey of popular Sufi shrines in contemporary East Punjab and included a vast array of both major and minor shrines. The survey entailed the study of old and new practices of the use of original/early images of saints and shrines for the creation of new mediated material such as collage posters, videos, paintings, animation and internet-based presentations which gets altered through transcultural impact and seek to influence newer generation of devotees and their popular piety. This would be helpful in understanding the linkages and reproduction of connections between east and west Punjab and within the region, which are mediated through popular memory and visualised both through visual arts and, modern print and electronic media.

A major repository of audio-visual material, both in print and electronic media, collected during these surveys consist of posters printed from several places in Punjab and Uttar Pradesh and CDs/VCDs/DVDs which play a major role in circulation of legends and local histories, creation of pilgrimage networks, development and standardisation of images of a popular saints and their shrines. These images consist of roughly three sets of production material. First set of images consist of large, medium and small posters, the second set consists of printed images produced for photo frames and the third set of images consists of such tiny versions meant for pocket and wallets. With an easy accessibility of print mediums, these images are also produced on photo prints at local studios.

This paper underlines the significance of audio-visual material and its circulation in the continued existence of popular Sufi shrines in contemporary East Punjab. It primarily focuses on four types of material. More important role in circulation of images is played by numerous production of electronic material in the form of CDs/VCDs/DVDs. Second set of material collected consists of poster and banners which are a major source of circulation. Book-covers and illustrations also constitute a fairly significant medium of circulation, especially the ones printed in local medium of Punjabi. The bulkiest material was in the form of digital photography and videography of shrine spaces and Urs personally done during surveys.

Popular Culture in Ferozepur and Bhatinda

Ferozepur district has had significant linkages with popular Sufi culture owing to its proximity with the shrines of Shaikh Farid (d. 1265) and Shaikh Bahauddin Zakariya (d. 1267), and its location on medieval trade route which integrated it with trans-regional cultural flows. The Chishti influence on Ferozepur is especially marked in the history of modern Punjab.8 Among important towns of the district was Abohar which was described by Ibn Batuta as the first town of Hindustan.

Fig. 01 |

Image-1 captures a popular Panj Pir shrine at Abohar in East Punjab. The shrine at Abohar is related to five Islamic saints of early medieval period. Kwajah Khizr a mythical saint is identified with river-god or spirits of wells, rivers and streams, and his principal shrine is on an island of the Indus near Bakhar in Sind.9 Baba Farid, one of the most revered Chishti saints who settled in Pakpattan. Shaikh Bahauddin Zakariya was a Suhrawardi saint who settled in Multan. Syed Jalal Bukhariya (d. 1291) and Lal Shahbaz Qalandar (d. 1274) who were disciples of Shaikh Bahauddin Zakariya and settled in Uch and Sehwan respectively. Panj Pir shrine possibly emerged along the medieval trade route which connected these major shrines associated with these sufi mystics after the thirteenth century and its association with the popular legend of Ramdev in the fifteenth century suggest that this tradition at Abohar developed between these centuries.10 The shrines pertaining to all these saints are in Pakistan. The sign board placed atop the entrance of the Panj Pir shrine has been painted with white and green colour, is the name of the shrine along with Islamic symbols '786' and 'crescent moon and star' and the name of the caretaker (sevadar) Bool Chand Kamboj who associated himself with Pakpattan in Pakistan.

Fig. 02 |

Abohar is also known for its Peerkhanas. The practice of constructing Peerkhanas (or abode of the Pirs) in Punjab has been recorded by colonial ethnographers.11 Most important constituent of these shrines are the memorial graves of the revered Sufis. Most of these Peerkhanas are concentrated in the adjoining regions of Punjab, Haryana and Rajasthan and are primarily controlled and managed by Aggrawal Sabhas of ‘Hindus’. Peerkhanas organise annual darbars (gatherings) to venerate Baba Lakhdata and Haider Shaikh.

Fig. 03 |

The flex banner disseminating information regarding annual mela (fair) at Peerkhana Abohar is printed in Devanagri script (Image-2). The darbar is attended by non-‘Muslims’ and led by Baba Makhan Lal Bansal, Baba Harbans Lal Garg and Baba Suresh Kumar. It is pertinent to note that Hindi is an important spoken language in the primarily urban areas of southern Punjab. Also, the communalization of the language question in the pre and post-partition Punjab gave primacy to the such scripts which were ascribed to religious identities, viz Devanagri for Hindus, Gurumukhi for Sikh and Shahmukhi for Muslims. Thus even while Aggrawal community in Punjab primarily converse in Punjabi, they use Devanagri script for writing. Thus the slogans in Image-2 are in Punjab language but the script is Devanagri. The other description, however, is in Hindi. The decorated memorial grave of Haider Shaikh is the centre of veneration at the annual darbar (Image-3).

Fig. 04 |

The city of Ferozepur is known for significant veneration to Hazrat Sher Shah Wali. He is an obscure saint and not much is known about his life. He is believed to have protected the town from Pakistan army invasion during 1971 Indo-Pak war.12 The langar hall of the shrine was constructed by Police Public Welfare Trust in 1999 and the Mosque by Sundari Bai. The elderly saint is usually depicted standing in front of a tiger (sher), wearing a white attire and red skull cap (Image- 4). He carries a white beard and long hairs and wears a white/blue/red garland. In another bust-sized image above the saint has a yellow halo around his head and is blessing two shrines in the premises, a Mosque and a dargah of the saint. The blessings are represented as emanating in the form of two rays of light which are inscribed with an invocation “jai babe di" (praise to the saint). Two white flowers emanating from top corners are inscribed with the numeric symbol "786". Image- 5 represents the grave of the saint along with the symbols of major religious traditions represented as one.

Fig. 05 |

Significantly, in many such images, the iconography is visibly an import from Hindu mythology but such adaptations necessarily emanate from local legends associated with mystics in the popular space. In addition, the use of iconography is not a taboo particularly in such popular shrines in both India and Pakistan. This has become particularly evident because of the wide popularity of the print medium.

Fig. 06 |

In the adjoining district of Bathinda, ‘Hindus’, ‘Muslims’ and ‘Sikhs’ claim Baba Haji Rattan to be their own. According to one legend, he was a companion of the Prophet Muhammad and lived for over 700 years. The first references to Haji Ratan in Islamic literature date back to twelfth century.13 The shrine of Baba Haji Rattan is associated with the popular legends of the visits of ‘Sikh’ Gurus; Guru Nanak, Guru Hargobind and Guru Gobind Singh.14 Image-6 represents devotees performing daily rituals and offering oblation at the shrine. The shrine is under the management of Punjab Wakf Board. An iron railing protects the grave of the saint and a large donation box is kept in the front. Besides this shrine, there is a Mosque and a Gurudwara named after Haji Rattan near the shrine.

Fig. 07 |

Image-7 captures a memorial grave of Shaikh Muinuddin Chishti (d. 1230) at Makhu Town in Punjab. Construction of memorial graves is an old tradition in Punjab. Often these are copies of such graves at the parent shrine associated with a Sufi mystic. Pilgrims carry sand from these shrines, bury it in their locality and construct memorial grave over it. Gradually, a protective domed enclosure is constructed over it and the place emerges as a local memorial dargah. Beautifully decorated with wooden engravings, Makhu shrine came up in the city in the year 2005. The grave is covered with a printed green chadar (cloth) with Islamic symbols and red rose petals sprinkled over the it. Another black chadar with images of Mecca and Medina and other Islamic symbols printed in golden colour is hanging on the other end of the grave. The shrine is managed by a Dalit-Christian popularly named Bohar who recently converted to Islam and assumed a new name Ghulam Farid Chishti.

There is also a hearth (dhuna mubarak) in a room adjoining the shrine and portrays a (‘Hindu’) trident and ‘Islamic’ panjatan pak (five holy members of the Prophet’s family) representing Sufi-Nath interactive traditions of medieval and modern India.

Celebrating Baba Farid

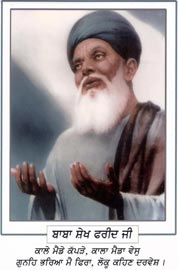

Fig. 08 |

Shaikh Farid is among the most popular saints of the region.15 Venerated by Sikhs and Hindus because of his significant verses complied in Guru Granth Sahib, the Sufi mystic is also popularly identified as a ‘Sikh’ saint. Image-8 is one of the two famous images of the Shaikh Farid. The image represents the elderly saint in prayer (dua) in an Islamic fashion. He wears grey turban, white attire over his body and carries a brown shawl. This image is particularly popular among non-Muslims of east Punjab. This image is from Faridkot and shares some resemblance with images of Christ and other such pictures on stories from the Bible. Apparently such representations are drawn from a common template of saint images. It is however difficult to ascribe definite source of origin for these images.

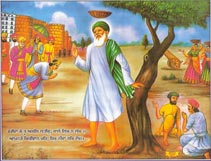

Fig. 09 |

Faridkot remembers Baba Farid his celebrated visit to the town (Image 9). The legend says that when Shaikh Farid visited the town (then known as Mokhalpur) the construction of the main fort complex was in progress. The construction officials forced the saint to work on the site and when a basket full of clay was kept on his head, it started floating in the air over Shaikh's head. When this incident was reported to the King, he apologised before the saint. Before the arrival of Shaikh Farid's several failed attempts to settle the city were made. Subsequently with the blessings of the saint, the city prospered and was renamed as Faridkot.

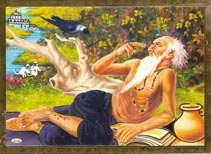

Fig. 10 |

Sikh devotees offer their prayer at the memorial shrine Chilla Shaikh Farid at Faridkot where the saint is thought to have rested (Image 10). The image portrays the popular image of the saint, five lamps, green flags and an old tree. The shrine also houses a Gurudwara within its premises. There is also a separate complex of a Mosque in the name of the saint adjoining the shrine under the management of ‘Muslim’ caretakers. During annual festivities celebrating the arrival of the saint (Shaikh Farid Agam Parb) several flex banners commemorating saint’s arrival are put up throughout the city by various political parties.

Fig. 11 |

There is a a popular legend of Baba Farid conversing with a crow and speaking the following couplet (Image 11);

The crows have searched my skeleton, and eaten all my flesh.

But please do not touch these eyes; I hope to see my Lord.

This image represents the elderly saint with long white beard and is almost bald. He is possibly narrating the above lines from his writings. He is bare-chested, wears a blue dhoti (waist cloth) and a necklace of multicoloured beads. His body has injuries at several places on the feet. The background represents a dense forest along with two white langurs in a playful mood located far away from the city. The saint is comfortably lying on a blue sheet along with a pot of water on his left. Embedded in a local landscape, this particular image can be located in several popular shrines in Punjab, painted on walls and occasionally the couplet written along with it.

Shrine of Haider Shaikh and Hafiz Musa

Fig. 12 |

Shaikh Haider’s shrine is the most popular Sufi pilgrim centre for the Sikhs and Hindus of Malwa region of Punjab. Image-12 captures the grave of the saint and pilgrims at the shrine in Malerkotla. Three devotees are sitting along the grave of Shaikh Haider (d. 1515); a ‘Muslim’ elder dressed in green sitting along with a ‘Sikh’ devotee wearing white clothes and a grey turban and a ‘Sikh’ woman in yellow clothes.16 The grave is covered with a maroon chadar (sheet). The legend of Nawab Sher Muhammad Khan writing a letter17 protesting against the Mughal emperor’s order to execute two sons of Guru Gobind Singh made the Suhrawardi Saint Haider Shaikh and the Nawab very popular among the non-Muslims of region.18

Fig. 13 |

The mausoleum of Haider Shaikh, which was originally built on a square plan with flat roof, has now been rebuilt and a dome has been placed on the roof. The walls of the tomb are decorated with glasswork. There are several minor shrines inside the enclosing outer wall which is seemingly of medieval origin.

Fig. 14 |

During annual Urs large number of Sikhs and Hindus visit the shrine and offer chadar (cloth) on the grave of Haider Shaikh. A drummer who is one of the descendants of Shaikh Haider collects offerings from the pilgrims (Image-13). Interestingly, the goat which is offered at the tomb as a sacred horse, is not sacrificed at the shrine. Some popular tracts in Punjabi and Hindi on the life and teachings of Baba Hazrat Shaikh Sadr-ud-din Sadr-i-Jahan popularly known as Haider Shaikh or Baba Malerkotla are sold outside the shrine (Image-14).

Fig. 15 |

A painting on the imposing arch at the entrance of Manakpur Sharif near Kurali draws the attention of pilgrims and possibly represents the image of a Sufi mystic (Image 15). Manakpur Sharif is among the largest shrines of the region. Dedicated to a Chishti Sabri saint Hafiz Musa19 (d. 1863), the early modern shrine was constructed by Shah Khamosh, his murid (disciple) who later settled at Hyderabad. This undated, unnamed and unsigned image is a wall painting drawn inside the right wall of the gateway. The image of portrays a mystic wearing long (brown) attire, red pajami (tight lower), a black jutti (footwear), holds a rosary in one hand and a red flower in the other. The posture of the saint suggests that the saint is old. The usage of colours suggests that the image was repainted with synthetic enamel colours. The entire wall is however painted with water colours which primarily include representation of flowers, creepers, leaves, etc. The celebration of annual Urs of Hazrat Hafiz Musa is popularised through flex banners extending congratulations of the festivities (Image 16). The organising committee of Lakh Data Lalan Wala Pir Nigaha, Tarapur Sharif has issued this banner.

Fig. 16 |

Fig. 17 |

Image-17 portrays the shrine of Shaikh Hafiz Musa. Set in a typical Chishti-Sabri style, the dargah has an architectural similarity with the shrine of Sabir Pak at Kaliyar in the state of Uttar Pradesh. Set on a square platform and approached through stairs in the front, the dargah has a square plan and the dome is also placed on a raised square plan. The shrine is painted with green and white colours. There is another smaller shrine on the left. The shrine also has a massive gateway at its entrance and a large mosque within the compound. The gateway is set in a regional form with an import of Mughal and Rajput forms of architecture. The most visible architectural features of the gateway include the ornate usage of archs, jharokha, dome, etc. The gateway is painted with red, white, green and yellow colours.

Divergence of Shaikh Sirhindi and Pir Bhikham

Sheikh Ahmed Sirhindi (d. 1624) was the most significant mystic of an orthodox Nasqbandi Sufi order and the founder of Mujaddidi doctrine in India. An exponent of wahdat-ul-shuhud, he was critical of the liberal Chishti discourse and wrote open letters to the Mughal emperor Jehangir criticizing Akbar policy of sulh-i-kul.20 The Shaikh is also disreputed for his angst against the Sikh Gurus.21 Every year, thousands of pilgrims from various parts of India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Bangladesh and other Muslim countries visit Rauza Sharif to participate in the Urs of Shaikh Ahmad Sirhindi.22 The tomb is set in the Mughal architectural tradition

Fig. 18 |

Modern Sirhind is a non-Muslim town but during Urs large number of Muslim pilgrims transform the landscape of the medieval town. Cooks from Saharanpur and various other parts of Uttar Pradesh put up their stalls and sell non-vegetarian and vegetarian delicacies like halwa parantha, etc (Image-18). The shrine space is marked by the graves of some significant personalities like Shah Zaman (d. 1844), the ruler of Afghanistan, who is buried near the shrine of the Shaikh, mausoleums of sajjada nishins, a serai and a large mosque.

Fig. 19 |

Image-19 is the cover of a book in Hindi on the saint and his philosophy and authored by Muhammad Ishaq and Muhammad Yakub of Malerkotla (Punjab). It also displays the image of the shrine. The literature on sale during annual Urs pertains to orthodox interpretation of Islam and is available in Hindi, Punjabi and English languages. Location of such literature in the larger realm of Chishti and Qadiri traditions in Punjab presents a complex paradox of competitive language of political Islam in contemporary India. In another instance, a book on the early medieval invader Muhammad bin Qasim celebrates him as a hero.

Fig. 20 |

In the same city, there is a minor shrine of a mystic situated in old Sirhind near Das Nami Akhara and popular among locals as the shrine of Baba Salar Pir (Image-20). A legend about the saint Baba Salar Pir locates him as a contemporary of Guru Gobind Singh. The shrine which is primarily visited by non-Muslims is a typical popular shrine with no roof. There is also a wrestling academy associated with the shrine, a tradition which is prevalent at a many popular shrines in Punjab.

Fig. 21 |

The shrine of Ghadam Sharif celebrates a lesser known legend about Saint Bhikham Shah (d. 1709), a Chishti-Sabri saint of Patiala.23 The legend narrates that when Guru Gobind Singh was born towards east of India at Patna, the Saint offered sajda (prayers) facing towards east. When questioned about the same by his murids he had told them that he has seen a new sun rising with the advent of baby Gobind Rai (who later rose to become the tenth Sikh Guru). Bhikhan Shah and his disciples then travelled all the way to Patna to have a glimpse of the infant Gobind Rai, apparently barely three months old then. Desiring to know what would be his attitude to the two major religious traditions of India, the saint placed two small pots of sweets in front of the child, one representing Hindus and the other Muslims. As the child covered both the pots simultaneously with his tiny hands, Bhikham Shah felt happy concluding that the new seer would treat both Hindus and Muslims alike and show equal respect to both.24 Painted on tin board in the year 2005, this image (Image-21) was located at the shrine of Pir Buddu Shah at Batala and portrays Saint Bhikham Shah (with a halo) along with his followers on the right and baby Gobind Rai (with a halo) held by his uncle Kirpal on the left, while a servant overlooks.

Fig. 22 |

Representing the narrative of Bhikhan Shah another image (Image-22) portrays a poor Brahmin Daula who was blessed by the saint to become the in-charge of the royal treasury under Mughal emperor Shahjahan. The saint apparently undertook an 'air' journey from his khanqah (residence) at Ghadam in Patiala to reach Delhi for participating in the royal meal hosted by Shahjahan. It represents the saint instructing the emperor Shahjahan and Wazir Daula Shah. Two murids of the saint are standing on the either side. The background represents rainy weather, image of a shrine, and religious symbols of Islam, Hinduism, Christianity and Sikhism. It is important to underline that the saint has a dominant following among Sikh and Hindu agriculturists of the region. Thus, while representing the core philosophy Islamic mysticism, utilization of such symbols enlarge the sacred space for divergent forms of identities.

Fig. 23 |

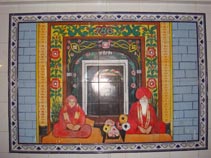

Ghadam Sharif has a large complex which includes a prayer hall, major shrine of the saint Bhikam Shah, shrine of his family and successors, a mosque managed by a Kashmiri Muslim and a langar hall besides large open spaces. The entrance is beautifully painted with enamel colours. The shrine is managed by gaddi nishins Baba Mast Diwana Bulleh Shah Ji and Bibi Mast Diwani Bholu Shah Ji (Image 23). It is pertinent to see the representation of women in contemporary shrine spaces. Bibi Mast Diwani occupies a place exactly parallel to Baba Mast Diwana and apparently articulates a radical status in an otherwise dominantly patriarchal rural landscape of Punjab. However, both these gaddi-nishins cater to the needs of their set of gendered pilgrims.

Immigrant Saints of Doab

Fig. 24 |

Jalandhar Doab region of Punjab is known for its typical nature of shrines. Set on an octagonal plan, these shrines present a coherent picture of such shrines from Jalandhar to Ropar. Image-24 captures the architecture and wall paintings at a popular Sufi shrine Mandhali Sharif in a village Mandhali in Punjab. The walls of shrine are beautifully decorated with modern enamel paint using bright colours. The early twentieth century wall paintings on the shrine, however, used water-based colours and dyes. The shrine attracts large number of immigration aspirants, especially young boys and girls and is thus also among the richest shrines in Punjab.

Fig. 25 |

Image-25 captures the nature of wall paintings at Mandhali. This particular photograph captures a painting on the inner wall of the dome atop the tomb of Baba Ali Ahmed Shah Qadiri (d. 1985). The upper circumference of the inner dome is pained as a sky and below is aerial view of Mecca. The neck of the dome is painted with floral patterns and inscribed with calligraphic representation of Allah. Significantly, Islamic symbols and sacred space represented in the paintings of this shrine are in contrast to the demographic landscape of Jalandhar doab which is bereft of mountains and is largely populated by non-Muslim peasantry. What one also needs to underline is that Punjab accounts for the highest 8.9 per cent of Scheduled Caste (SC) population in India (Census 2001) and Jalandhar together with the adjoining districts of Amritsar and Ludhiana alone account for more than half of scheduled caste population in the state. This demographic pattern, along with the caste tensions between dalits and Jats (who have dominant control over Gurdwaras in Punjab), is visible in the former’s large presence and participation in various festivals organised at this shrine.25

Fig. 26 |

Baba Ali Ahmed Shah Qadiri is usually portrayed on the wall paintings (Image-26) sitting in a contemplative mood and being attended by several of his followers which include Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims both men and women. The background of the painting represents Mecca and Medina on both sides, and the scene of a fair on the right corner below. The saint dons green attire and wears ear and nose rings. These set of images articulate a feminine typology sufi mysticism where the murid yearns for union with the divine. In the more contemporary images (Image 27) such representation becomes symbolic and is juxtaposed with the display of growing wealth around the gaddi nishin Sai Gulam Baqi Bille Shah (d. 2009). Sai wears several necklaces, earrings, nose ring and rings in his fingers. He is portrayed holding cigarette in the left hand and currency notes in the other. There is also a hoard of currency notes in front of him. Sai Bille Shah has particularly been popular among Punjabi NRIs and frequently visited his devotees in the west.

Fig. 27 |

This image is a montage and Sai’s image is apparently superimposed on the image of the shrine. This medium of producing images has become particularly popular with the availability of contemporary editing techniques that enable artistic alignment of multiple images as against coarser cut-paste arrangement performed earlier.

Fig. 28 |

Music concerts (sama) are also an essential component at the annual Urs of Baba Gulame Shah at his shrine in Banga. Punjabi folk artist performances with modern orchestra instruments based on classical compositions of Waris Shah, Bulleh Shah, etc. and personal compositions of the performing artists are regularly recorded and circulated among devotees. Image-28 captures a different kind of musical and dance performance outside the shrine of Baba Gulame Shah (d. 1965, a sister shrine of Mandhali Sharif) during annual Urs held at Banga. The image portrays eunuchs dressed in western/Indian attire performing in front of a sizeable audience which comprises of Sikhs and Hindus. It is pertinent to note that shrines of Baba Abdullah Shah Qadiri and his successors are significantly popular among gays, transgender and eunuchs.26

Two Musicians and Two Saints

Fig. 29 |

There are two significant shrines related to Baba Murad Shah and Baba Lal Badshah respectively at Nakodar. Beautifully decorated with coloured tiles and floral patterns these are one of the most popular shrines in the Jalandhar Doab. These saints and their respective shrines have significant presence on the internet sites like Youtube and Blogger, and social networking sites like Facebook.27 This is perhaps the result of the association of these shrines with two famous Punjabi singers Gurdas Mann and Hans Raj Hans, both of whom are also significantly popular among the diasporic Punjabi community. Presence of shrines and their gaddi nishins on the internet makes possible the transnational location of these centres.

The gateway to the shrine of Baba Murad Shah (Image-29) is beautifully decorated with coloured tiles painted and printed with floral patterns and images of the patron Qadiri saint Murad Shah, Baba Ladi Shah and Baba Ami Chand among others.

Fig. 30 |

On the barrier created towards the approach to the shrine of Baba Murad Shah (Image-30) the sacred symbols of dominant religious traditions have been painted. These religious symbols include 'crescent moon and star' and '786' (Islamic) on both the sides, 'Ek onkar' (Sikhism), 'Om' (Hinduism), 'Cross' (Christians) in the centre and reflect upon the unitary principles of major religious traditions. One reductionist way to understand the representation of these symbols at such shrines could be to indeed link them to the political economy of the sacred centre, the clientele of the shrine. However, in a non-Islamic space these symbols also articulate an ideology of liberal discourse of the Chishti and Qadiri Sufi mysticism and dissent the dominant religious discourse.

Fig. 31 |

Memory constitutes and important component of everyday existence of popular Sufi shrines in contemporary Punjab. Representation of ‘popular’ murids along with their Pir constitutes an important mode of sustaining shrine’s relationship with popular piety. Thus when Baba Ladi Shah of Nakodar, who recently died at Nakodar, is located in the memory of Gurdas Mann (dressed in the traditional green kurta and lungi) sitting and contemplating on his Pir (Image-31), the latter appears to him through the zannat (mountains). This representation articulates the centrality of Mann’s relationship with the Pir and his role in the present day management of the shrine which has been bestowed upon him by nature itself. The hedge, which physically separates the Pir and the murid in time, however, connects them through memory.

Fig. 32 |

Similarly, Image-32 represents Baba Lal Badshah of Nakodar who is the patron saint of popular Punjabi Sufi/folk singer Hans Raj Hans. The saint recently died at Nakodar. Hans Raj Hans (dressed in traditional white kurta and lungi) is represented sitting before a garden (zannat) and praying before his Pir who is seated on a sofa in one image and blessing the singer from the other image, thus separating yet connecting the singer with his pir through memory and ‘chosen grace’.

Sufism at a Sikh Pilgrimage Centre

Fig. 33 |

Amirtsar and Batala constitute an important component of popular Sufi shrines and practices in the border region of Majha. This region is particularly popular for veneration of Baba Lakhdata, Gugga Pir and Khwaja Khizr and has significant influence of the Chishti Sabri silsila through the shrine of Kaliyar Sharif which plays an important role in the circulation of literature, mystic ideology (via ritual intermediaries and musicians) and create a network of shrines from Amritsar and Batala to Patiala. Image-33 captures the front and back cover of a book on the life and miracles of Hazrat Sabir Pak of Kaliyar Sharif which was in possession of a murid at Amritsar. On the top of the front cover is the image of shrine at Medina from where the larger image of Kaliyar Sharif descends.

Fig. 34 |

At the annual Urs for Baba Lakhdata (Image 34) organised in the walled city of Amritsar Baba Meshi Shah from Batala (from the dargah of Hazrat Buddhu Shah) is received by Baba Gope Shah (from the walled city). A jubilant murid (follower) is dancing in the backdrop. The fair is attended dominantly by non-Muslim audience (except for migrant Kashmiri Muslims artisans who participate)28 and is organised under the banner of Anjuman Ghulame Chishtiya Sabriya an umbrella organisation of Chishti Sabri followers in Punjab which includes Hindus and Sikhs from several castes.

Fig. 35 |

At the popular shrine of Zahra Pir, a banner (Image 35) advertises the sale of chadar, patasa and fulli (sweets) for offering and agarbatti (incense sticks). It instructs the visitors to deposit their shoes at the shoe counter. The signatures on the right corner below mentions the name of J.S. Arora (a ‘Sikh’). The shrine of Zahra Pir houses a memorial grave of the Pir and several smaller shrines dedicated to Khwaja Khizr, Hindu goddesses, Sai Baba, etc. the shrine is primarily visited by Hindus and Sikhs.

Fig. 36 |

Zahra Pir is represented riding a white horse, wearing white attire, a green turban and waistcloth, holding a stick in one hand and blessing with the other (Image 36). There is a halo behind his head and an Islamic symbol of crescent moon and star on the right amidst the starry sky. Five lamps are lit in the front on a platform or a grave dedicated to the saint. Significantly, the shrine of Zahra Pir at Amritsar is under the control of Punjab Wakf Board and was probably under the supervision of ‘Muslim’ caretakers in the pre-partition times. It is now under the supervision of a ‘Hindu’ caretaker. There are several shrines in Punjab which though controlled by the Punjab Wakf Board, are run by non-‘Muslim’ caretakers. Wakf Board collects and annual ‘rent’ from the latter who performs the role of a ritual intermediary of these shrines.

Walled city of Amritsar is dotted with several minor shrines dedicated to Khwaja Khizr, a water deity popularly known as Jhule Lal. This saint is venerated (as Varun devta) among Hindus and Sikhs of the walled city. Legend associates this saint with traders and seafarers who believed and wished that the saint protects them during their journey to pursue long distance trade. As an Islamic saint, the legend of Khwaja Khizr has been popular among merchants and sailors.29 At several of these shrines, annual Urs (fairs) are held regularly. The image of saint is represented in several forms engraved and painted on a copper plate, placed as an idol and more popularly printed on glazed sheets. As an elderly saint standing on/riding a yellow fish, garlanded with fresh flowers, wearing a green/red/yellow attire, holding a stick in one hand and a 'holy book' in the other. There is a halo behind his head and the sea/ocean/river in the background.

Fig. 37 |

In the poster art of Khwaja Khizr, the saint is represented as a deity of the water whose major shrine is in Sukkar (Pakistan). As a Hindu deity, he is portrayed with a temple in the backdrop and as an Islamic saint, he is represented wearing a green attire.

In the popular iconography at the walled city of Amritsar, Khwaja Khizr (Jhule Lal) is located along with Gugga Pir on the one side and the family of Shiva (including goddess Parvati, son Ganesha, Brahma and a Shivalinga on the other (Image 37). The shrine has several other images of Khwaja Khizr and an aarti (hymn) for him in Hindi superscripted with Islamic symbol '786' can be located on the right wall of the inner hall. A Hindu priest from the state of Uttar Pradesh manages the shrine.30

Fig. 38 |

The adjoining town of Batala constituted a major centre of Islamic learning in medieval India but was destroyed as a result of raids by Banda Bahadur in early eighteenth century. It was also a residence of several Qadiri saints.31 After the partition of Punjab many shrines were left desolated until new occupants took over them. Many such shrines developed new lineages (where the identity of the older shrines was unknown) and new sajjada nishins emerged. At a minor shrine of Pir Buddhu Shah at Batala, Baba Meshi Shah Chishti, the present caretaker and the Pir of the shrine is represented along with his wife standing before the larger frame of shrine at Mecca and Medina, and Qur’an (Image 38). This is another example of an image produced in a local lab, locating the regional within in the larger Islamic space. This shrine is also connected with the Chishti Sabri network in the region.

Landscape of Popular ‘Pirs’

Fig. 39 |

Within the modern landscape of Chandigarh there is a shrine dedicated to Baba Lakhdata and an adjoining Mosque of the Chishti Sabri tradition. The location of this shrine in Chandigarh is a significant example of how a popular tradition transcends different urban and rural landscapes. The signboard (Image 39) atop the entrance of this memorial shrine attributes it to Baba Lakhdata.32 One of the oldest of such shrines in the city, the shrine is managed by Chishti Sabri Muslims associated with the shrine of Shaikh Hafiz Musa at Manakpur Sharif. The shrine is also known as Khanqah Baba Nazir Chishti Sabri or Peerkhana Sabri Masjid. Islamic symbols '786/92' and 'crescent moon and star' are superscribed on the signboard. It is significant to note that Hindus and Sikhs devotees offer dua at the memorial shrine in a typical Islamic fashion.

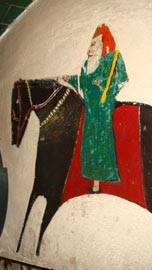

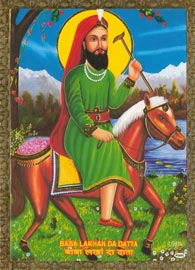

Fig. 40 |

It is pertinent to observe that in all parts of Punjab, Baba Lakhdata is represented as riding a horse. In fact, most of the early legends associated with such Pirs often narrate saint’s advent on a horse.33 While iconography of this phase is extant, one such, probably, early modern representation of an elderly Baba Lakhan Da Data can be located on the wall of the inner sanctum (Image 40) at one of the oldest shrine of Pir Nigaha at village Langiana (District Moga).34 The saint is represented riding a black horse. Dressed in green attire, black jutti (shoes), and wears a red headgear along with an impression of a kalgi. He holds a yellow stick in his left hand and reins of the horse with the other. The image does not carry the name of any artist. This painting possibly gives a glimpse of representation of the saint much before the advent of printed posters.

Fig. 41 |

Image-41 captures the landscape of Nigaha (Shrine) of Saint Lakhdata at District Una in Himachal Pradesh. The major shrine of Baba Lakhdata who is primarily known as Sultan Sakhi Sawar is located in Dera Ismail Khan a frontier district in Pakistan. After the partition of Punjab non-Muslims who venerated Baba Lakhdata reconfigured the significance of pilgrimage and the memorial shrine of the saint which is known as chotta (minor/small) Nigaha assumed major significance where a large fair is also organised every year. This image visualises a popular representation of Baba Lakhdata on the right sitting on a horse dressed in green attire. The image in the centre is closer to the representation of Shaikh Abdul Qadir Jilani (Gaus Pak). Both these images are blessing the shrines located on the left, images of Khwaja Khizr, graves in the shrine complex, the langar hall (community kitchen), etc. Below is also the representation of a boy wearing a Muslim cap and offering dua. The representation of dua in popular poster art articulates the acculturative significance of Islamic symbols among non-Muslims.

Fig. 42 |

Jalandhar, Nawanshahr and Ludhiana districts are dotted with numerous major and minor shrines dedicated to Baba Lakhdata. The popular iconography of Lakhdata in these districts in particular and Punjab in general is represented either in standalone posters or in idols casted in cement and painted with bright enamel colours. The most popular poster of the saint (Image 42) represents a contemplative Baba Lakhan Da Data riding a decorated brown horse. He is dressed in green attire with a red waist belt, red jutti (shoes) and a necklace of white beads, and wears a red headgear along with a white kalgi. He also holds a stick and has a yellow halo behind his head. The landscape behind the saint comprises of snow-clad mountains, clear blue sky, distant trees and a portion of a near tree with a creeper in full bloom, a lake with lilies and grass with wild flowers on ground beneath. This poster might have originated in Pakistan since the landscape represented in the backdrop is perhaps that of Dera Ismail Khan where the principal shrine of the saint is located. The only hill shrine in India is at Una which does not experience snow. Besides golden border, the image of the saint and the horse is embossed at several places with golden print replicating the golden embellishment which became popular in the Mughal paintings in medieval India. Annual Urs are organised in the memory of Baba Lakhdata and other popular saints in all parts of Punjab.

Fig. 43 |

On the other hand contemporary flex medium is used to advertise and disseminate information pertaining to a qawwali programme being organised in the memory of Shaikh Muinuddin Chishti at Nawanshahr (Image 43). The participant qawwals are Balli and Prem. The banner in Punjabi has been issued by the organising committee of Rauza Khwaja Garib Nawaz and portrays the image of the popular Islamic saint Khwaja Khizr, juxtaposing him with the announcement for the Chishti saint and the image of an unidentified shrine in the backdrop, everything enclosed within a foliated arch. The usage of imaging software makes possible the harmonious location of several images in a banner. Such banners are different from the more crude images prepared in a local photo studio.

The invention of flex banners as a contemporary print medium, together with the easy availability of computer editing techniques, has also enabled the translocation of an image which was earlier limited to a specific region, but can bow travel to new locales through internet and print medium, and gets narrated in native language.

Fig. 44 |

Yet another medium of wall paintings mostly copy printed images and translocate the narrative tradition of Shaikh Abdul Qadir Jilani (Image 44) popularly known as Gaus Pak in the Indian subcontinent.35 Gaus Pak was the patron saint of the Qadiri Sufi order which was founded in Baghdad after his death in 1166 AD. Although Gaus Pak never came to India, he became popular in the country through emigrant Qadiri sufis who later arrived in India and several stories of native genre get associated with him. Earliest among Qadiri saints was Shaikh Muhammad al Hussaini who settled in Uch (now Pakistan) in the beginning of 15th century, though legends associated with Gaus Pak continue to be more popular than any other Qadiri saint of medieval India (except Mian Mir of Lahore). Also, among Qadiri saints it is primarily Gaus Pak who is popularly represented in images. A major Roshni Fair is annually dedicated to Gaus Pak at Jagraon (district Ludhiana). It is primarily attended by non-Muslims.36

The popular iconography of Gaus Pak (Image 44) narrates the story of a woman Rudi who on one occasion forgot to pay her donations towards Gyarvi Sharif. In the same week, it was her son’s wedding and people invited on the wedding ceremony had to ferry across a river. As soon as the ferry took off it started to sink. After watching this happening, the mother had so much depression that for eleven/twelve years she kept wandering in a jungle. One day she met a faithful who queried her about the problem. After hearing the problem, he said asked Rudi to raise her hands and supplicate to Allah. After supplication to Allah the ferry that had sunk around twelve years ago started rising. Everyone except one emerged safe. The friend of Allah asked the woman, “Did you remember to donate generously towards the Gyarvi Sharif?” The woman replied “no”. He told her that she should keep donating generously to Gyarvi Sharif. Narrating this tale people strongly recommend celebrations at Gyarvi Shareef on the eleventh day of every month.37 The story continues to be popular in east Punjab. In the backdrop of the image is the shrine of Gaus Pak at Baghdad. Rudi is praying to Gaus Pak and subsequently the saint rescues the ferry carrying her relatives.

Adjoining this image is the painting of Gurdas Mann a patron of Qadiri tradition and the most popular folk and pop singer of Punjab. These paintings are painted on the outer wall of the shrine a Chishti Sabiri saint Sheikh Hafiz Musa at Manakpur Sharif and articulate the popular significance if the liberal Qadiri and Chishti Sabiri tradition in the local environment.

Fig. 45 |

Gugga worship is another significant aspect of saint veneration spread across the entire north Indian plains including Punjab and a major fair Chapar Mela is organised annually in the month of February at Ludhiana.38 The significant part of this veneration is the idiom of Pir associated with this legend. In the flex banner (Image 45) outside the shrine (darbar) of Gugga Pir, the saint is represented wearing a red attire, riding a white horse with a spear in one hand, followed by Bhajju Kotwal and blessing devotees with the other, welcomed with garlands by women of the household. Smaller images along with the 'Five deities' above blessing Gugga from the blue heavens and a Nath saint Machendranath, depict various episodes from his life.

While the description of the image of Gugga is in Hindi the name of the shrine is written in Punjabi. This beautifully exemplifies the import of an image of a tradition from the non-Punjabi region of Rajasthan and its translocation through the medium of internet.

Fig. 46 |

Baba Ramdev is one of the most revered popular saint of adjoining state of Rajasthan and also has following among Bagris of southern Punjab. The most significant aspect of this veneration is the narrative of debate between Ramdev and the Panj Pirs of Abohar in Punjab.39 Image 46 in the centre depicts Ramdev riding a white horse welcomed by women of the household. Ramdev is dressed in red/pink attire, with a garland around his neck, red/golden crown and a halo behind his head. He holds a spear in one hand and blesses with the other. The image depicts various episodes from his life, primarily his birth, marriage, performing miracles, and meeting with Panj Pirs, etc. On either side is the representation of the presiding deity at Ramdevra, the pilgrimage centre of Baba Ramdev. It is interesting to underline the shared templates of popular iconography. Pir or a mystic riding a white horse perhaps transcends the limits of representing a ‘Hindu’ or a ‘Muslim’ saint in a larger cultural zone and depict Baba Lakhdata, Gugga Pir or Baba Ramdev through common templates of iconography, also connecting other with popular myths and encounters between these legends.

Fig. 47 |

Two most famous and celebrated Punjabi Sufi mystics poets Bulleh Shah and Waris Shah get portrayed in a poster most possibly copied from Pakistan Punjab (Image 47). Bulleh Shah’s poetry (kafi) and philosophy presents a radical critique of Islamic religious orthodoxy of his times. Waris Shah’s seminal work on the legend of Heer-Ranjha, the story of romantic love in a Sufi genre, is considered one of the most significant contributions to Punjabi literature. Waris Shah, while critiquing orthodox ulema, instead locate popular ‘Hindu’ and ‘Muslim’ mystics as objects of veneration.

Fig. 48 |

Image 48 captures a flex banner of a roadside shrine of Baba Rode Shah at Faridkot. The banner portrays the elderly saint wearing green attire and sitting in a posture with his hands around his legs. The banner also gives information about two annual fairs held at the shrine, and langar (community kitchen) organised every Thursday. Interestingly, the image of Baba bears striking resemblance with the popular image of Baba Tajuddin of Nagpur. This shrine is possibly a memorial shrine named after the major shrine of Baba Rode Shah near Amritsar.40 There is another memorial shrine associated with Rode Shah in the Patiala city.

Configuring Popular Saints.

Fig. 49 |

Popular posters represent a significant element of inter-faith dialogue and widen the possibilities of shared sacred spaces. These posters seek to standardise the pathology of popular sacred spaces and its constituents which are gathered from various dominant religious discourses. Image-49 represents a white horse and a canopy below which there is an image depicting five fingers of an open hand and symbolizes the five members of the holy family namely Prophet Muhammad, Ali, Fatima, Hasan and Hussain. This representation popularly known as khamsa. It is an important icon for most Shias and constitutes a significant element of Sufi shrines in contemporary Punjab. Khamsa which is usually located along with the Shaiv trident near a furnace (dhuna), for instance, at the popular shrines in Makhu and Nawanshahr is probably a symbolic representation of acculturation between early Sufi and Nath practices in Medieval India.

Fig. 50 |

The holy family has also been personified in the popular iconography (Image 50). It portrays five members of the Prophet’s family; Prophet Mohammad in the middle, his son-in-law Imam Ali (holding a sword), daughter Fatima (Ali's wife) in burqa and his grandsons Hassan and Hussain (seated in the lap of the Prophet). An angel, probably Jibreel (Gabriel) apparently holding Qur’an, is also represented standing behind Muhammad along with the popular calligraphic symbol of the sacred five (panjatan pak) in the top left corner. This image probably has its origin in Iran and its early version can be located in the digital collection of University of Bergen (Norway).41 Panjatan pak is also represented along with Zuljinah, the sacred white stallion which reminds of the battle of Karbala.42

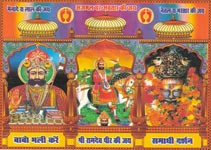

Fig. 51 |

Popular religion operates through an organic interplay of folk ethnology, geographical landscape and sacred spaces. In the particular context of Punjab, this interplay has been articulated in the veneration of popular saints. In the popular iconography, this is represented as an amalgamation of thirty-seven Indo-Muslim popular saints from the diverse landscape of Punjabi sacred sphere (Image 51). It includes images from both the dominant traditions as well as heterodox saints, though superscribes the centrality of sacred cosmology of Islamic traditions. Abdul Qadir Jilani is seated in the centre. Another larger variant of such posters from Pakistan has been documented by Frembgen (2009, pp.10-11) where he underlines the imaginary imagery of a gathering (khayali mehfil) which is attended by fifty-seven Indo-Muslim saints surrounding Shaikh Abdul Qadir Jilani. There is a striking similarity in the selection of a majority of Islamic saints in this particular poster. But what is more striking is the inclusion of apparently some non-Muslim saints in this poster.

Fig. 52 |

Image-52 represents three popular saints on a greeting card in circulation at Amritsar. The three saints namely (left to right) Khwaja Khizr, Sai Baba and Krishna are holding hands of each other. Khwaja Khizr is wearing white/green attire, Sai Baba white and Krishna is wearing yellow/red attire. The background scene represents a cloudy day and possibly a river flowing from distant mountains and partially visible sun reflected in the water. The location of Sai Baba’s image in the centre suggests that this greeting card articulates the philosophical basis of the saint’s teachings emphasising universal brotherhood. It is pertinent to note that Sai Baba’s identity has been a matter of debate among his ‘Hindu’ and ‘Muslim’ followers. His teachings, however, amply illustrate his philosophical insight into unitary nature of diverse religious articulations.

Fig. 53 |

One of the most popular poster of saints venerated in the region include mystics of the Chishti, Qadiri and Qalandari lineage (Image 53). Significantly, these were also more liberal as compared to Suhrawari and the Nasqbandi orders. This poster can be located at all Sufi shrines in Punjab and depicts the images of popular Sufi saints and their respective shrines, connecting important sacred centres in the region.43 These images are suggestive of a network of popular wilayat (landscape) of saint veneration in Punjab. All these shrines (except those of Baba Farid and Shaikh Abdul Qadir Jilani) are located in India. While Shaikh’s Farid shrine is compensated with the memorial location of visit at the Faridkot town, Shaikh Jilani’s memorial shrines can be found in all parts of Punjab. These shrines also perform the function of pilgrimage and circulation of images connect Punjab with Delhi and Rajasthan on the one hand and west Punjab on the other. Also visible are the shrines of Mecca and Medina on the top.

Along with the images of popular saints of the region, posters pertaining to saints in others parts of India are also in circulation at shrines in contemporary Punjab. These images focus on visual representation of saints like Baba Tajuddin of Nagpur (Maharashtra), a Sufi mystic of the nineteenth century India44, Baba Sailani Shah mian whose shrine is located in Buldhana district of Maharashtra near Aurangabad, the legendary Ghazi peer from the Sunderbans (Bengal)45; also popular Islamic posters which focus on Qur’anic calligraphy and combines verses from Qur’an with images of shrines and events related to the Prophet, descriptive representation of Surah (chapter) 36- Yaseen from Qur’an; the images of shrines of Masjid Haram at Mecca, Masjid Nabwi at Medina, Masjid Aqsa at Jerusalem, other sacred shrines around Arabia; Islamic symbols of 'crescent moon and star' and '786'; Burraq, a flying horse with the head of a beautiful woman that Prophet Muhammad rode for Meraj, his journey to the heaven; image relating to the tomb of Prophet at Mecca and the footprints of the right foot of the Prophet; and Zuljenah-e Hazrat Imam Hussain from the battle of Karbala.

Among these images, the poster of the shrine of Shaikh Muinuddin Chishti is most significant because Punjab has had traditional linkages with the shrine of Ajmer Sharif.46 The popular Image of Imam Ali is in circulation at all major and minor Sufi shrines of Punjab. Another important element of posters is the ethical promotion of Islamic virtues and reading Qur’an and performing dua (prayer), and is done through popular description of a young girl wearing gold ornaments and ornate clothing offering dua in an Islamic fashion. There is an image of Mecca and Medina in the backdrop and a copy of Qur’an on the left. In a non-Muslim space, such images articulate an important element of acculturation of Islamic objects of piety.

Audio-Visual Circulation

Fig. 54 |

An equally significant medium of circulation of images and memories of Pirs and dargahs are modern disc formats of songs, qawwalis, qisse, etc. on compact disc (CD), video compact disc (VCD) and digital video disc (DVD). The easy production and reproduction of these formats at local studios has virtually wiped off conventional cassettes from marketplace. These discs primarily focus on production of audio recording along with dramatic performances narrating the legends and life of popular Pirs (saints). These audio recordings are also mixed with the musical performance of singers and images of Pirs and shrine spaces. An important function of these productions is the reproduction of popular Punjabi folk compositions from Pakistan which includes albums of Alam and Arif Lohar, Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan and Rahet Fateh Ali Khan, among others. The centrality of these four singers at sufi shrines can be felt at almost every urs organised in Punjab where, in absence of local qawwals, these compositions are played on several occasions. Image 54 captures the sale of audio-visual collections at the annual Urs (fair) of Shaikh Hafiz Musa. These collections comprise of qawwalis, gazals, geet (songs), lectures, etc in Punjabi, Hindi, Urdu and English.47

Fig. 55 |

Among these, the VCD reproduction of qawwali compositions of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan are most popular. The front cover of Image 55 portrays the popular painting of the popular love legend of Sohni Mahiwal on the top and Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan's (the legendary Sufi qawwali and singer of Pakistan) photograph below. Produced at Jalandhar, similar reproductions on Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan are also available through production houses in Phagwara and Delhi.

Fig. 56 |

Qawwalis constitute an important element of production with primary focus on qawwals from Malerkotla in Punjab.48 Besides, many other collections on Kaliyar Sharif, Ajmer Sharif, Baba Lakhdata, and Ramzan, etc produced outside the state are also in circulation. Image 56 is a VCD collection of popular qawwalis sung by Maqbool Ahmed (Nazar Ali) of Malerkotla. The front cover of the album portrays the image of the singer along with the image of a popular legend of Shaikh Abdul Qadir Jilani. Production centres located in Delhi focus primarily on the qawwals of Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan and sung dominantly in Urdu. Productions in Punjab, however, focus on Punjabi compositions. The subject matter of these compositions constitutes qawwalis sung for Muinuddin Chishti, Gaus Pak, Sabir Pak and Baba Farid, besides local compositions for Baba Lakhdata and Haider Shaikh.

Fig. 57 |

Image 57 is a VCD collection of popular music sung on the eve of Ramzan by Anuja, Sandeep, Radha, Geetika and Nazim. The front cover of the album portrays the image of the singer and the image of Jama Masjid, New Delhi. There is a wide variety and diversity in the profile of singer and actors that include Muslims, Hindus and Sikhs.

Fig. 58 |

The cover of Image 58, a telefilm on Baba Lakhdata, portrays the image of the saint on the top and the image of the actors below. This music album is produced by Payal Music, Bathinda (Punjab) and sung by Harinder Sandhu, Harnek Gharu, Gurtej Komal, Muhammad Jirpal, Maanjir Kaur, Ranga Khan Langeana, Makkan Mastana, Gurjant (Jatta), Manjit Mannu and Vishal Masti. Albums on Baba Lakhdata are also produced from Himachal Pradesh and Rajasthan.

Fig. 59 |

Music and video productions on Pirs of the Doab recreate the life and on some occasions are first attempts to record their narratives/histories. Image 59 is a VCD collection of Punjabi compositions sung by Jamna Rasila, presented by Mintu Uppal and produced by P.S. Sodhi. Produced at Nur Mahal, the front cover of the album portrays the image of the singer and others, and the images of Baba Lal Badshah and his successor Sai Lovely Shah. Similar productions on the history of shrine Mandhali Sharif, Banga and its successors, productions on current debates on Islam and interfaith dialogue are also in circulation.

Fig. 60 |

Image- 60 is a DVD album of lectures by Dr. Zakir Naik who is the founder and president of the Islamic Research Foundation (IRF)49, which is a non-profit organization that owns Peace TV channel based in Mumbai, India. A prominent Muslim figure in the Islamic world, Naik is also a public speaker and a writer on the subject of Islam and comparative religion. The front cover of the album portrays the image of Zakir Naik holding Qur’an and the Vedas. Similar productions on various themes of Islam and particularly a debate on ‘Misunderstandings about Islam’ among Devanand Saraswati, Zakir Naik and Roshanlal Arya, are also in circulation.

Fig. 61 |

Also significant are the productions of Sufi Foundation India which organises Sufi musical concerts in Punjab. 50 Image-61 is a collection of Sufi compositions sung by some of the most renowned singers from both sides of Punjab. Produced at Chandigarh, the cover of the album portrays the image of six popular saints of Punjab sitting around the copy of Qur’an. The inner cover portrays Abida Parveen and Hans Raj Hans singing their compositions.

Conclusions

Circulation of images plays a significant role in contemporary articulation of saint veneration at various Sufi shrines in Punjab. Partition meant not only the catastrophic migration of people, reconfiguration of demography and division of physical boundary of the region; it also divided the sacred landscape of Punjabi religious sphere. In the post-partition scenario, it is the reproduction of images of Sufi mystics and their shrines in west Punjab and other parts of Islamic world which has kept alive the memories of saints like Shaikh Farid, Shaikh Bahauddin Zakariya, Lal Shahbaz Qalandar, Shaikh Abdul Qadir Jilani, Bulleh Shah and Waris Shah, etc. Besides, the images of popular/folk saints like Sakhi Sarwar/Lalan Wala Pir of Nigaha in Dera Ghazi Khan and Khwaja Khizr of Bakhar among others. The shrines associated with these saints are continually recreated in the popular spaces of contemporary east Punjab and more recently among Punjabi NRIs.

Modes of image production and its circulation is a significant tool to understand translation of pre-partition memory in the current scenario and emergence of new network of shrines in contemporary east Punjab. It needs to be underlined that after 1947 Sufi shrines continued to exist and after a brief period of lull many of these were taken over by new caretakers who reconfigured shrine’s relation with new demographic transformation in the wake of partition. There were such minor shrines which were never recorded in historical texts and the new caretakers reconfigured their relationship with the existing Sufi silsilas in India. Significantly this social formation has remained unrepresented in the colonial and post-partition historiography of Punjab. Current trends of historiography continue to focus on conflict between Sikhism, Hinduism and Islam and deny any possibilities of organic relationship particularly between Sikhism and Islam. Rose had mentioned in early twentieth century that Guru Gobind Singh was bitterly opposed to Islam without looking into the lived experience of social landscape of Punjab.51

This paper critiques such communal representations of historiography of Punjab. Significantly, even in the post-partition scenario, saint worship and pilgrimage to Sufi shrines continues to be a vibrant tradition in east Punjab. Though networks of Sabiri shrines existed in several places from Kaliyar to Lahore, Kaliyar Sharif (Roorkee) has more recently emerged as the most significant guiding shrine for absorption of unknown shrines with new sets of lineages and networks of Chishti pilgrimage, linking them with other major shrines at Ajmer, Panipat and Delhi. Amritsar and Batala, for instance, which was known for its Qadiri links with Lahore owing to Hazrat Mian Mir is now known for its intimate relationship with the Chishti Sabiri silsila. This new relationship is mediated through organisation of Urs in the walled city throughout the year where qawwals from Kaliyar perform. Kaliyar helps in legitimising Punjab’s relationship with Shaikh Farid and Baba Lakhdata. Sabir Pak was a murid and khalifa of Baba Farid. This new relationship is further mediated through popular ‘Sabri’ identity.

Images also reflect upon the nature of pilgrims who visit the shrine. It is pertinent to note that even at places like Malerkotla and Ropar which has significant Punjabi Muslim population, it is the Sikh and Hindu veneration for the Sufi saints like Haider Shaikh and Hafiz Musa which is most prominent. Shrines are thus marked as shared spaces of popular veneration. It is through the images of these saints and their shrines that popular traditions are replicated across the rural and urban landscape of Punjab. Peerkhanas at Abohar and adjoining areas in Haryana and Rajasthan, and dedicated to a Haider Shaikh and Baba Lakhdata are primarily run and managed by non-Muslims. A majority of them emerged in the last decade of the twentieth century. These shrines also define the nature of pilgrimage and ritual practice. Significantly, the Sabri tradition while retaining the Islamic modes of dua, ardas and kalima, interweaves the shared Punjabi tradition of saint veneration by emphasising the unitary principles of Guru Nanak’s teachings and significance of Guru Granth Sahib as a shared religious text.

Besides images of qawwali darbars, saint veneration also assumes significance through mediation of folk and modern pop singers who have based a majority of their productions on Sufi literature. Most popular among these are Wadhali Brothers, Gurdas Mann and Hansraj Hans. The image of these stars with their Pir also plays a significant role in transcultural circulation among NRIs. Cable networks and more recently websites like Youtube broadcast several clippings of live performances by these singers at popular Sufi shrines.52 These recordings, together with recent technological invention of compact discs and its digital versions has led to mass circulation of such audio-visual productions. These audio-visual productions of popular devotional videos about Sufi shrines are at times dramatically videographed in a studio or staged settings. Qawwali reproductions from west Punjab, most significantly by Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, are available at all major or minor Urs at popular Sufi shrines in Punjab. Such production centres are located in the entire region and adjoining states of Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Delhi, Haryana and Himachal Pradesh and enable interlinking of various shrines of the region.

These productions emanate from major cities of Punjab like Jalandhar, Phagwara, Ludhiana, Bathinda, Malerkotla and Chandigarh and even minor cities like Banga, Nur Mahal, Moga, Mandi Gobindgarh, and semi-urban centres like Khamano and Jhunir too. Circulation of productions from Jawali Mukhi in Himachal Pradesh, Panipat in Haryana, Ajmer and Padampur in Rajasthan, Lucknow and Hamir Pur in Uttar Pradesh and significantly from New Delhi can be easily located at various urs, dargahs in cities and villages of contemporary Punjab. The covers of these productions are inscribed with images of shrines and pir of the region. Circulation of images of shrines like Kaliyar Sharif and Deva in Uttar Pradesh, Ghaus Pak in Gwalior (Madhya Pradesh) and Ajmer Sharif (Rajasthan) also constitute a significant flow of images. Similarly, with the localisation of production transcultural flow of images and legends get altered and adapted in the local environment. Significant music production of legends songs, qawwalis dedicated to Pirs and dargahs includes performances of non-Muslims particularly folk singers and even young artists.

Posters pertaining to Urs at shrines in Uttar Pradesh at several places in Punjab are crucial in circulation of images in the regional, sub-regional and local context. Posters related to various shrines in Punjab were found in associated shrines in the region which were again crucial in building network of shrines and pilgrimage in the region. There were three set of posters in circulation. The traditional ones in single-colour print were more visible in the rural areas and minor shrines, while multi-coloured posters were marked in the major cities of the region. Modern print medium of digital flex printing was also especially marked in urban centres where large hoardings and smaller banners of shrines and associates were visible.

Books and pamphlets in regional Punjabi medium, Hindi and Urdu are also in circulation at popular Sufi shrines. Texts and images inscribed on their covers (front and back) also play a significant role in standardisation of history, legends and narratives about a local saint or his shrine. Since major visitors at popular shrines belong to either rural populace or urban dalits (which also constitute majority illiterate population), this medium is less popular among them. The medium is however popular among the urban and rural literates. These book-covers and illustrations continue to be a relevant resource for circulation of images and narrative hagiographies of popular Sufis and their shrines which get translated into audio-visual productions. In the case of Mandhali Sharif an audio-visual production in 2010 has been the first attempt to record the local narratives of Sufi mystics.

The composition of shrine-spaces is perhaps the most significant constituent of social production. While images and their circulation perform an important task disseminating memory, shrines spaces are actual indicators of articulation of popular beliefs systems. Photography and videography of these shrine spaces, especially during Urs, consisted of recording pilgrim profiles, identifying the structural markers of shrines- their architecture and landscape, nature of sanctum sanctorum, ritual performance, wall murals and paintings, etc in the shrines complex, nature of Urs and its cultural production and makeshift market places and items on sale.

Shrines in Jalandhar Doab have assumed standardised layout and Mandhali Sharif has played a significant role in this respect. Similarly, Peerkhanas dedicated to Haider Shaikh and Baba Lakhdata in southern Punjab have assumed standard patterns. Significantly, the shrines in Doab reflect upon the medieval and modern Sufi culture and are primarily signifiers of Mughal and Rajput architectural traditions (besides Gurudwaras). All Sufi shrines in Punjab, barring Rauza Sharif at Sirhind, are marked by the presence of Hindus and Sikhs of all castes. Ritual performance, although localised, have significant import from Islamic practices and ritual traditions at Kaliyar Sharif and Ajmer Sharif are guiding principles which influence everyday performance at Sufi shrines in Punjab. Graves of Sufi mystics or memorial graves constructed in rural and urban landscape of east Punjab assume immense significance in replicating memories of Sufi mystics. Urs celebrations thus become major markers of ritual performance and rekindle memories of Sufi shrines in India, Pakistan and the other parts of the Islamic world.

Saint worship in contemporary Punjab is also a continuation of early Sufi and Nath interactive traditions. Shrines dedicated to Khwaja Khizr, Shaikh Muinuddin Chishti, and Baba Lakhdata are significant exemplars of these interactive traditions. Khwaja Khizr is celebrated as the saint of wells and has its origin in traders’ veneration for the saint who travelled distant areas through oceans, seas or rivers. In the Indian context it coexists with veneration of the Varun devta and evolves into a shared tradition of saint worship which continues to be a vibrant tradition in the walled city of Amritsar. Similarly, the shrine dedicated to Shaikh Muinuddin at Makhu also houses a hearth which locates and celebrates the Nath shaiv trident and Shia panjatan pak. Also at every shrine dedicated to Baba Lakhdata placement of hearth and existence of image/idol of Bhairav (Shiva’s dreadful form) is an essential component of shrine space and saint veneration. These practices emphasise the continued significance of the liberal discourse of Sufism in the evolution of an ‘organic’ interaction between several religious traditions.

There is also an important element of political economy associated with these shrines. It is pertinent to note that while memories of shared past continues to be relevant in the existence of Sufi shrines in contemporary Punjab, the larger issues of caste relations in the state are also significant. In the post partition scenario, the assertion of dalits has been a significant element of social formation. This assertion is reflected in the growing influence and significance of Deras in various parts of the state and perpetual conflicts between Jat Sikhs and dalits. In several cases, this has translated in emerging significance of dalit politics and shrines associated with saint Valmiki and also emergence of separate Gurudwaras for dalits in rural and urban landscape of Punjab. This element of assertion is also reflected in the growing significance of Sufi shrines among dalits. However, it is just one element of these Sufi shrines, but they do provide scope for absorption of multiple caste and religious identities because of liberal discourse saint veneration. Thus, large numbers of desolate Sufi shrines in contemporary Punjab are significantly managed by dalits.

There are important linkages between modern poster representations of Sufi mystics and early representation of saints in the form of wall paintings and sketches at various Sufi shrines of Punjab. The most significant example in this case is that of Baba Lakhdata. Pilgrims buy and carry images of shrines and saints for veneration and constitute important link to circulation and standardisation of images in contemporary Punjab. Images also juxtapose shrines with their successors, caretakers along with images of major Islamic shrines, symbols of various religious traditions, liberal usage of Islamic symbols and represent a cross-cultural perspective to understand the nature of Sufi shrines in contemporary East Punjab.

1 David Gilmartin, Empire and Islam: Punjab and the Making of Pakistan (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1989), 41-42.

2 Gilmartin, 43-45.

3 Claudia Liebeskind, Piety on Its Knees: Three Sufi Traditions in South Asia in Modern Times (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1998), p.2.

4 Author’s work on Panj Pir shrine at Abohar exemplifies how its geographical location on the medieval trade route led to the emergence of a distinct form of veneration of saints associated with five Sufi shrines on the trade route between Sindh and Abohar. Author, “Historicity, Orality and ‘Lesser Shrines’: Popular Culture and Change at the Dargah of Panj Pirs at Abohar,” in Sufism in Punjab: Mystics, Literature and Shrines, ed. Surinder Singh and Ishwar Dayal Gaur (New Delhi: Aakar, 2009), 402-429.

5 In the context of a paper on Panj Pir tradition at Abohar, author highlights the continued significance of the popular Sufi shrine in contemporary social formation of Punjab. Author, 402-29.

6 Shrines of Chishti saints like Baba Farid, Suhrawardi saints like Shaikh Bahauddin Zakariya and Syed Jalal Bhukhari, Qadiri saints like Mian Mir, early mystics like Shaikh Al Hujwiri, popular shrines of Sakhi Sarwar and the deras of Nath Jogis with whom early Sufi mystics interacted are located in Pakistan and the shrines of Suhrawardi saint Haider Shaikh, Nasqbandi saint Shaikh Ahmad Sirhindi, Chishti saints like Shaikh Muinuddin, Qutbuddin Bakhtiyar Kaki, Nizamuddin Auliya, Shaikh Ali Ahmed Sabir, Shaikh Sharfuddin Panipatti and Shaikh Hafiz Musa, etc. are located in northern India, besides numerous minor saints and their shrines on both sides of Punjab.

7 Farina Mir argues that saint veneration is better understood as constituting a parallel, alternative spiritual practice that was accessible to all Punjab’s inhabitants. Literary representations in Punjabi popular narratives such as Hir-Ranjha suggest that people participated in saint veneration without recourse to or invoking pre-existing religious identities. The practice involved the reinterpretation of piety and constituted beliefs that stood alongside formal categories of religious identity, without being in conflict with them. The repeated depiction of this form of devotional practice in the most ubiquitous Punjabi cultural form suggests the importance of this social formation in Punjabi popular imagination, and in Punjab’s religious and cultural history. Farina Mir, “Genre and Devotion in Punjabi Popular Narratives: Rethinking Cultural and Religious Syncretism,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 48, no.3 (2006): 755.

8 Besides existence of several Sufi shrines, the district was also known for presence of a distinct category of population who called them Chishtis and drew ancestry from Baba Farid. The ancestory of the Fazilka Chishtis crossed Sutlej from Pakpattan somewhere in the middle of the eighteenth century and constituted a holy tribe. They had largest presence in Muktsar and Fazilka Tehsils of colonial Punjab. Punjab8 District Gazetteers, Ferozepur District 30, no.A (Lahore: Superintendent, Government Printing, Punjab, 1915), p.100.

9 For an interesting reading on the cult and representation of Khwaja Khizr in Persian and Mughal art, read Anand K. Coormaraswamy, “What is Civilisation” and Other Essays (Cambridge: Golgosova Press, 1989), 157-167.

10 For a detailed discussion on dating this tradition, see Author, 410-15.

11 The Punjabi landscape of colonial times was dotted with saints’ shrines called Peerkhanas. Built on the boundaries of the village out of plastered hollow brick cubes, they were eight to ten feet in each direction, covered with a dome and with low minarets or pinnacles at the four corners. In front was a doorway which generally opened out in to a plastered brick platform. Beyond the doorway there were two or three niches for lamps, but otherwise the shrine was kept empty. Every Thursday the shrine was swept and lamps were lit. The same day the guardian of the shrine, a bharia, collected offerings from the village to the sound of drum. These were mostly grain and came especially from the women. Harjot Oberoi, “Popular Saints, Goddesses, and Village Sacred Sites: Rereading Sikh Experience in the Nineteenth Century,” History of Religions 31, no.4 (1992): 371.

12 It is interesting to note here the apparent role that the buried saint played in the protection of Indian Territory of Punjab became particularly significant in rhetoric of Indo-Pak wars fought on several occasions along the Radcliffe Line since 1947. In another such instance of 1971, the sevadar of the Panj Pir dargah at Abohar organized a langar service for the Indian Army for a period of three months when it was stationed near the dargah. Author, 427.

13 Mohammed Ayub Khan, “Religious Fusion in the Subcontinent,” The Milli Gazette, April 16-30, 2005. For a more detailed account of Haji Rattan and his shrine, see Subhash Parihar, “The Dargah of Baba Haji Ratan at Bhatinda,” Islamic Studies 40, no.1 (2001): 105-132.

14 Rose mentions several other versions of the tradition of Baba Haji Rattan. H.A. Rose, A Glossary of the Tribes and Castes of the Punjab and North-West Frontier Provinces Vol. 1 (Delhi: Low Price Publications, 2008), 551-52.