Mediating Belief: Dawat-e-Islami's Emerging Madina of Visuality

Noman Baig

9/11 brought the US government and the Western media’s sharp focus on Pakistan’s religious organizations, operated relatively free from interference or control by the Pakistani state. The militant Islamist networks of the region were allegedly using this religious space to promote their projects against the West. Thus, tropes of Islam, violence, and tribalism became strongly associated with both Pakistan and the forms in which its people conduct religious practices. Yet, this image is far from the lived realities and experiences in the Sunni religious organization, Dawat-e-Islami (Invitation to Islam), based in Pakistan’s largest city, Karachi. Founded in 1981, by a perfume vendor, Ilyas Qadri, Dawat-e-Islami’s religious activities hum with ritual practices that are far from representations of “Islam” that dominate global airwaves. For example, Dawat-e-Islami (DI) uses its website to offer instructions for the Islamic practice of receiving God's guidance known as Istekhara (divination), for making important business and marriage decisions. Also, for becoming Ilyas Qadri’s disciple (mureed) one simply needs to fill out an online form. 1 Moreover, Dawat-e-Islami is the first and only religious organization that broadcasts its TV channel, Madani, in Pakistan and to several continents. Thus DI is an apt starting point for a discussion on how emerging forms of media are deployed to propagate religious beliefs.

The sudden proliferation of television channels under the rule of military dictator, Pervez Musharraf (1999 – 2008), introduced a new visual landscape in Pakistan. Fueled by the rising tide of anti-Americanism, and the US war in Iraq and Afghanistan, news channels broadcasting politically and emotionally charged talk shows gained rapid popularity. Television networks such as Geo, owned by the largest media group, Jang, and ARY Digital, named after Pakistani-Gujarati gold merchants, Abdul Razzak Yaqoob, from Dubai, were the first two privately-run channels to emerge in post-9-11 Pakistan. As a result of a relaxation in media law, a number of new channels hosted live shows on domestic and international issues ranging from everyday life problems such as marriage and divorce to the US' war on terror. Public broadcasting of hitherto private matters transformed the country’s media industry. For instance, a live religious talk show, Aalim Online, on Geo TV, became popular because it was a service that provided solutions, in line with ‘Islamic principles,’ to people's daily domestic concerns. It was soon after that exclusively religious channels began to enter the predominantly news and entertainment related media industry. Islamic channel such as Quran TV (QTV) was launched exclusively to air the devotional genres of qawwali and naat, and religious sermons.

Fig. 01 |

Within this context, DI launched its first television channel, Madani, in 2008. The opening of a TV channel surprised people because DI had historically been a vehement critic of the television. It had adhered to the belief that visual imagery spread evil and was, thus, a source of moral degradation in society. Figure 1 is the cover page of the organization’s pamphlet titled, Destructive Effects of T.V., depicting fire on a flat screen TV, indicating that watching television would result in the burning in hell. The seven chapters presented in the book indeed emphasize bodily punishments for TV viewers. Some of the titles are: Venomous Lizards, Terrifying Centipedes, Corpse in Pain because of (watching) TV, God's curse on one who buys TV for their children. These chapters provide a detail description of the corporeal punishments endowed upon people who commit the sin of watching television. “These titles are catchy”, informed one of DI’s students, Munawwar Attari, at the organization’s mosque, “they trick people reading them into thinking that it is some kind of a story but they soon discover that a book presents lessons about punishments for sinners.” “Hazrat sahib [Ilyas Qadri, founder of DI] understands people’s sensibility that is why he chooses these titles to grab people’s attention” the student added smiling.

Fig. 02 |

However, as I elaborate further below, DI is gradually transforming its views against TV and visual images by embracing modern visual technologies, making themselves and their services available to a global audience. Its Madani channel broadcasts live religious shows, devotional singing in praise of Prophet Mohammad or naats, and sermons from the organization’s headquarters, Faizan-e-Madina, in Karachi. Never seen on TV before, the organization's leader, Ilyas Qadri, appeared on air for the first time with the launch of Madani channel in 2008. DI also produces multimedia CDs, religious software, and mobile phone applications for a variety of users searching for new ways of experiencing religion. DI's user-friendly website offers many services from the live TV channel, to online chat rooms/forums, and wallpaper downloads. In addition to Madani channel, the organization also maintains interactive website, Facebook and Twitter pages connecting them to followers across the world.

Through an ethnographic study of the organization in Karachi, the research analyzes Dawat-e-Islami’s visual media; pamphlets, stickers, and emerging audio-visual materials. I argue that the popular medium of booklets and stickers are slowly receding giving way to emerging ephemeral and visceral forms of communication such as mobile SMS and videos. The organization has shifted its focus towards media technology to advance organization’s values, and has opened up new ways of interaction between religious belief and visual media in Pakistan. Despite the surge in the use of multimedia technology to disperse religious values, little effort has been made to understand this growing relationship in Pakistan.2 The question then I raised is how media and religion are entangled with each other, and how it is reconfiguring the shape of human experiences. For the current research I have focused primarily on the ways in which religious organizations like Dawat-e-Islami deploy media technology. To understand its impact on the human experience requires different sets of methodology and detailed ethnographic research which is beyond the scope of the present study.

Historical Background

Born on July 12, 1950 in Bombay Bazaar in Karachi, Ilyas Qadri’s ancestors came from Kutiyana (Junagarh) in India.3 Hailing from an ethnic Gujarati community, which is the predominant merchant group in Pakistan, Qadri started selling perfumes (attar) in local markets. His connection within merchant networks in bazaar settings offered him a building ground upon which he would eventually establish an international organization. It was his brother’s death that transformed this small perfume vendor into a self-reflecting pious person.4 Shaken by his brother’s death, Qadri started addressing his friends on the topics of death and the grave. Soon he found a more collegial place, a local mosque called Gulzar-e-Habib in Soldier Bazaar, Karachi, to deliver more structured sermons. The topic of death became so central to Ilyas Qadri’s sermons that the discourse continues to be a dominant theme after DI’s formation. Combined with the pre-existing Barelvi belief system (explained below) and merchants’ finance, Ilyas Qadri soon rose to popularity and in 1981 founded Dawat-e-Islami in Karachi. Ilyas Qadri came to be referred by the title of Amir Ahle-Sunnat (Leader of the followers of Sunnah), Sheikh – e – Tarikat (Chief of Methods), Baani –e- Dawat Islami (Founder of Dawat-e-Islami) or simply Bapu (Father).5

Literally translated as Invitation to Islam, the organization draws its ideological views from the teachings of the eighteenth century Sunni reformer, Ahmad Raza Khan (1856 – 1921) from the north Indian town of Bareilly, in Uttar Pradesh. Ahmad Raza Khan headed a powerful religious movement known as Ahle Sunnat wal Jamat, popularly referred to as Barelvi in South Asia.6 Dawat-e-Islami became the main proponent of Barelvi ideology -- following the Sunnah (traditions of the Prophet), recitation of devotional poetry such as naat, and expressing deep reverence for sufi saints. It is in the spirit of venerating Sufism that the founder and followers of DI adopted the word Qadri as their last name from the patron saint of Baghdad, Abdul-Qadir Jilani. Because of its reverence for sufis and recitation of devotional poetry, the organization encountered opposition from several literalist traditions, particularly from another famous north Indian school, Madrassah Deoband. In Pakistan, Tablighi Jamat (TJ), a proselytizing organization, represents Deobandi teachings. TJ strictly prohibits deference to anyone other than Allah, thus vehemently disagreeing with DI's reverence for Sufism.

Although DI claimed a strictly apolitical nature and insisted only on disciplining the self according to sunnah, the organization enjoyed popularity in Karachi's neighborhoods and towns and consequently had street power. It approached at the grass-root level by organizing street corner congregations of Quranic teachings (Dars-e-Quran). In Dars-e-Quran, people stood at street corners to hear lessons on religious observance given by a preacher, who was often a former MQM activist or leader.7 One interesting fact about these popular Dars-e-Quran meetings is that despite their apolitical message they were not held inside mosques. Rather they took place widely and frequently deep in neighborhoods that were formerly MQM strongholds. These probably served to de-ethnicize Mohajir youth. The preachers’ vivid descriptions of heaven and hell and of Judgment Day aimed to scare youth away from irreligious activities, and most importantly, from politics. DI’s dedicated cadre would persuade and sometimes even force people to stay and listen to the moral lessons (dars). The preachers issued Fatwas (edicts relating to the banning of “non-Islamic” practices) against activities such as cricket and gyms, and urged youth to adhere to a lifestyle similar to Prophet Mohammad’s. These techniques did little to divert youth from indulging in violence; however, it offered them new language to refashion their identities that eventually led towards further religious sectarianism.

DI's rising popularity and rapidly increasing religious sectarianism allowed the group's politically oriented members to form a political party that could compete in electoral politics. Thus, the traditional and apolitical DI gave rise to the militant Sunni Tehreek (ST), founded by Riaz Hussain Shah.8 A thirty-two year old Gujarati-Mohajir, Saleem Qadri, rose through the ranks very quickly and eventually headed the organization. Under his calculative leadership, ST’s popularity grew, and the group flourished due to its “genius of organization and acquisition of funds.”9 Slogans such as “Sunnio nay Sher Paala, Saleem Qadri ST [Sunni Tehrik] wala” (The Sunnis reared a lion, Saleem Qadri from ST) were a common graffiti in Karachi’s political landscape. Sunni Tehrik which is closely aligned with Dawat-e-Islami is now headed by Sarwat Ijaz Qadri. On the streets of Karachi, one can read the praise for the ST’s leader; “Sunnio ka Jungi Jahaz, Sarwat Ijaz Sarwat Ijaz” (Sunni’s fighter jet, Sarwat Ijaz Sarwat Ijaz). Jihadist organizations like the Sipah-e-Sahaba Pakistan (SSP), influenced by Saudi Arabia’s ultra-conservative Wahhabi brand of Islam, also emerged as strong forces in the climate of growing Islamic extremism.

Fig. 03 |

Claiming to have active members in more than 100 countries across the globe,10 DI is mostly concentrated in Karachi and receives its financial support from wealthy Gujarati merchants. Since Ilyas Qadri and the senior members belong to the Memon ethnic group, the organization has been successful in procuring large amount of resources from Gujarati merchants who finance the organization’s events, offer gifts to naat reciters, and donate large amount of cash in these gatherings. Through the merchant’s generous financial support, DI constructed a huge organization headquarters called Faizan-e-Madina in Karachi. The building can hold thousands of people at a given time while also maintaining massive five stories dorm rooms for male student studying Quranic and Hadith courses in the madrassah as shown in Fig. 3.

Every Thursday evening after Maghreb prayers, DI holds weekly congregation (ijtema) at Faizan-e-Madina. Because of an increase in the number of participants as well as security concerns, DI simultaneously holds 6 more separate ijtemat (gatherings) in towns that are too far from the headquarter. Despite the disbursement, thousands of people continue to come and listen to sermon which DI records in order to broadcast on Madani channel. Four cameramen, two in the front and one in the back of the audience, and one facing the preacher who delivers sermons (from behind what appears to be a bullet-proof glass), record the entire show. Two big TV sets are also placed in front of the audience who can view it live. The preacher usually invokes the most gruesome imagery of Judgment Day and what will happen to people who did not believe in the Prophethood of Mohammad. While depicting a vivid scenario, occasionally the preacher cries and begs for Mohammad’s grace in order to provide them sanctuary from the torturous pain of the day. To provide further relief from the monotony of the sermon, the preacher frequently intersperses naat verses which are quickly reiterated by a professional naat reciter. The naat reciter’s melodious voice grabs people’s attention and the bodies move in synchrony with the rhythm of the naat. The entire sermon thus is a performance that usually lasts for an hour.

Although it broadcasts TV shows and has embraced video filming and photography of its naats and sermon gatherings, the organization strictly prohibits any footage of women or female members seen in public, even if their faces are veiled. Despite adapting a plethora of visual technologies and having female followers, the organization's attitude towards women remains conservative at best, evidenced by their exclusion of women from sight. Women's invisibility is ensured not just through religious and social norms but also through spatial ordering. For instance, during social and religious gatherings, women are secluded off-scene away from 'male gazes.' In DI's headquarters (markaz), Faizan-e-Madina, in Karachi, halls for female members have separate entry and exit points thus keeping women subjects as minimally visible as possible. The booklets published on the topic of women's veils are innumerable. So while it may appear at first glance that adopting new technologies is evidence of modernization or Westernization, this in fact serves to further sideline women as they become even more invisible.

The Making of a Madani via Media

Dawat-e-Islami publishes thousands of booklets (kitabchay), stickers, pamphlets, fliers, and more recently, has ventured into virtual space via the Internet, television, and mobile phone technology. One of the most common media that the organization has deployed to spread its message is the medium of stickers. Printed on glittering papers, smaller in size, and take little effort to paste on a surface; stickers can be seen in shops, marketplaces, buses, rickshaws, government office, household, and other places. Through these stickers DI offers religious iconography and prayers that encourage people to strive towards the higher ethical values in accordance with Sunnah. Aligning one’s life with Sunnah requires enormous efforts and this can be achieved by disciplining bodies and performing prescribed rituals. DI encourages its members to strictly obey the prescribed guidelines in order to become a true follower of Prophet Mohammad and to transform oneself into Madani.

Fig. 04 |

Becoming a Madani refers to sets of practices and expressions, arising from a deep reverence to the city Madina and to Prophet Mohammad, that DI’s followers perform in order to inculcate Sunnah. Members of DI express deep love and passion not only for Prophet Mohammad but for the city of Medina as well. After migrating from Mecca in 622 AD, Mohammad and his followers settled in Medina to form an Islamic ummah or community organized according to the principles of Islam. Considered to be the first city of Islam, Medina is also revered because it is home to Mohammad’s grave. Blessed by the presence of the Prophet Mohammad, everything related Madina thus acquires a special status in the organization's order of things. The wind, trees, sand, and mountains of the city are highly deified and praised in sermons and naats, which tie people's subjectivity with the inanimate objects of Medina as well.

The objects of Medina embody spirituality and divine qualities. Most importantly, the mosque, Masjid-e-Nabwi, (The Mosque of the Prophet) shown in Fig. 4, built by Mohammad and his followers, resonates in DI's sermons, naats, and every type of media. Masjid-e-Nabwi's green dome is the most widely recognizable symbol of the organization. The organization firmly believes the road to Allah runs through the alleys of Medina. Thus the word Medina becomes synonymous with holiness, spirituality, and peace. In the organization's discourse, merchandise, relationships, or events embodying some kind of “texture” of Madina are referred to as madani (literally means “from Medina”). Most of the naat collections or sermons are titled “Madani collection/volume,” “Madni phool” (flower), “Madni Kafila” (caravan), and “Madni guidance,” etc. Passionate followers of DI even go so far as to refer to people as “Madni bhai (brother),” or “Madni munna (baby/child).” Madina has become a label used to refer to anyone who shares a similar sense of longing and passion for Mohammad's city as remembered by the organization's members.

Fig. 05 |

After the image of Medina, the most important symbol in the organization's order of things is the Prophet Mohammad's foot print called Nalain Pak. Revered as a blessed symbol, Nalain Pak comes in different colors and types – stickers, buttons, fliers, posters – but the shape stays the same. Fig. 5 depicts what is believed to be Mohammad's foot print which is located in the center surrounded by arch-shaped boundaries. Since the symbol is an image of Mohammad's shoe it is widely revered as a spiritual object thus having divine qualities. Sometimes, men wear a Nalain Pak button on the front and center of their green turbans.

Fig. 06 |

Adorning the symbol of the shoe, considered the dirtiest or lowest piece of clothing, on one’s head, is a display of deep love for Mohammad. Another popular sticker that can be seen in almost every public space is shown in Fig. 6 which reads “Hum per Nazar Karam Ya Rasul Allah” (Bless us with your Gaze, O Mohammad). This prayer requests that Mohammad alleviate the reciter’s suffering (of various kinds) with his holy gaze. The metaphoric use of the word, nazar (gaze), embodies a powerful feeling that Mohammad is still alive and his attention can help one through worldly sufferings. This glittery sticker with the chant printed on it is seen pasted on buses and rickshaws and the phrase itself is popular in naats and at sermons.

Fig. 07 |

Another popular prayer, which in fact is one of the organization’s trademarks and which differentiates it from other religious groups is the phrase “Peace be Upon You, O, Prophet Mohammad” as shown in Fig. 7. Inscribed on the mosque's gate and recited before the call to prayer (azaan) five times a day, this slogan is the emblem of Barelvi ideology. The significance of this can be understood by the fact that in DI's mosques, the muezzin – a person who calls to prayer - chants this slogan first in the microphone and then begins the azaan. Saying 'Peace be Upon You, Oh, Prophet Mohammad' before the azaan has caused controversy and conflict between DI and other purists religious sects. For the literalists, the only word allowed before starting anything is the name of Allah who is the most beneficent and merciful. Deviations from the name of Allah would only lead a person or organization to a wrong path and thus outside of Islam.

Fig. 08 |

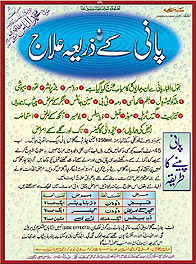

DI also emphasizes how to maintain one’s bodily health as this is necessary for a strong community. It publishes hundreds of ways to cure diseases without any modern or even traditional medicine, based on the belief that natural ingredients have medicinal qualities if consumed in accordance with the Sunnah. A lengthy poster on water and its benefits is an apt example as shown in Fig. 8. The flyer describes the benefits of drinking water and the ways it cures diseases. Surprisingly, one is instructed to drink 1250ml (4 large glasses) of water early in the morning before brushing their teeth, which, according to the flyer, cures a number of diseases. There are also instructions for the proper method of drinking water. In Fig. 10, the poster’s title, “Treatment through Water,” overlays a blue background with a drop of water creating ripples with extensive text underneath, explaining the benefits of water. At the bottom, the chart displays categories of types of diseases, amount of water, and the time period for a cure. Similar posters, booklets, and pamphlets are available explaining how to cure diseases with fruits and dates. They even claim to cure serious illnesses and diseases such as cancer, hepatitis, AIDS, etc. Similarly, the Fig. 9 shows four different kinds of stickers; a clay pot, a water bottle with a glass, a jug and glass, and a 5 gallon water dispenser bottle, instructing people on the proper methods for drinking water.

Fig. 10 |

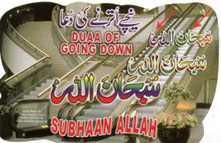

In addition to a cure for almost everything, DI media offers prayers for almost every imaginable activity. Fig 10 shows a prayer recommended when one is ‘going down’. When a person walking down the stairs he/she should recite “Subhan Allah” or Glory to Allah. The image shows modern escalators glimmering with light, mirrors, steel, and glass, resembling a shopping Mall in an oil rich emirate like Dubai. The text written over it is in three different languages: English, Urdu, and Arabic. These stickers are a frequent sight in Karachi’s public places such as shopping centers and government buildings, reminding people to express the name of Allah since He is the one who gives the ability to walk.

Fig. 11 |

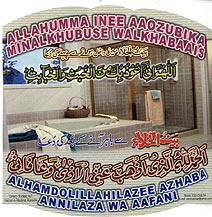

Another example is the Fig. 11, which shows a modern bathroom with a bathtub, shower cabin, and neatly stacked towels – a luxury rarely available to the people in Pakistan except, of course, for the elite class. The top of the sticker reads, “A prayer before entering a bathroom,” and the bottom of the sticker, “A prayer after leaving the bathroom.” Reciting these two prayers before entering and after leaving the bathroom is supposed to protect one from evil.

Fig. 12 |

What used to be the content of booklets is now increasingly becoming part of the visual landscape of public spaces through the medium of stickers. Stickers and posters prescribe prayers for everyday life actions such as walking and bathing. Mohammad Ikram Attari, a shopkeeper on the first floor of Faizan-e-Madina, has been in the business of selling stickers for more than 16 years. His shop’s name is Variety Stickers as shown in Fig. 12. The shop has wide range of stickers, about 500-600, that he usually designs with the help of a designer. “Stickers cost Rs.3, 5, 15, and 20 each but not more than that” informed Ikram. “People asked me how do you make your living by selling these inexpensive stickers,” to which I replied, “deen ka kaam hey, is mein barkat hai” (This is a work of faith, it has grace). “I do not see any impact of digital media on my business” claim Ikram. “God gives me bread” said proudly. I have six members in my family and I support all of them with this business. I even had the opportunity to take my entire family to Hajj” Ikram said with satisfaction. “These are popular stickers and people will encounter them on a frequent basis if they are pasted in different places” told Ikram. “They will learn these prayers if they see pasted somewhere” said Ikram. Memorizing and then remembering these prayers – available for almost every activity of a person's life – could prove to be a challenging task. These stickers, pasted at the entrances of public toilets, and many other places, ease the effort of remembering.

Members of the organization physically transform themselves in their appearance. For instance, the green color, which is the color of Masjid-e-Nabwi's dome and which also signifies Islam, has become an important visual marker since DI followers adorn a green turban (hari pagri). DI members, as shown in Fig. 8, wear a bright green turban as a sign of identity among the organization and to express their attachment with sunnah. The unconventional color of the turban not only makes it a hallmark of the organization but in everyday parlance, a member of the DI is referred to as a hari pagri wala (one with a green turban) or jannat kay totay (parrots of paradise). Wearing a green turban with a contrasting white dress of shalwar qameez, miswak (a tree branch use for cleaning teeth), attar (perfume) and bright yellow sandals, members of DI make themselves appear distinct. The organization believes that one has to fully transform himself/herself, spiritually and physically, according to the sunnah, in order to reach taqwa (a state closer to God). Thus these things are instrumental in subject formation which is manifested in its clear form in the bodily comportment and affective state of an organization's members.

Fig. 13 |

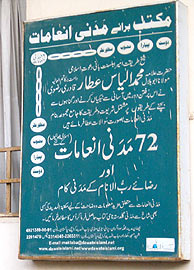

This level of devotion towards Madina and Prophet Mohammad does not end on few slogans. Rather, the DI has issued a set of short books called Madani Inamat (Madani Gift) that lists a number of questions on activities that a person is supposed to follow in everyday life. The questions pertain to ordinary rituals such as prayers, washing, talking, eating and drinking, performed in accordance of sunnah. If an act follows a sunnah guideline, for instance, drinking water while sitting, then the person checks the box. DI has introduced these books for men, women, children, male and female students, and for deaf and mute. Following is the breakdown of the books:

72 Madani Inamat for Men (as shown in Fig. 13),

62 Madani Inamat for Women,

25 Madani Inamat for the deaf and mute,

30 Madani Inamat for male students,

and 83 Madani Inamat for female students.

This practice of marking everyday performance in the booklet is called Fikr-e-Madina (Thoughts of Madina). At the end of each month, a person needs to submit the book to a nigran (supervisor) who then eventually submits it to the Faizan-e-Madina. In this way the nigran and senior DI’s members supervise and cast a surveillance net on people’s daily behavior. A unique aspect of these books is that it is aimed to record every activity that a person conducts in his/her everyday life.

Fig. 14 |

In addition to discipline people’s daily behavior, Dawat-e-Islami also controls their code of conduct by instilling fear of death among its followers. In recent years, the organization has started using multimedia technology to deliver sermons that heavily emphasize the condition inside a grave. The Fig. 14 shows a DVD titled, Qabr ki Pehli Raat (First Night in the Grave), which is Ilyas Qadri’s video sermon on the topic of death. The aim of the sermon was to meditate on deaths and to make people aware of the transient nature of material life. The preacher offers a vivid torturous picture of what happens inside the grave of a sinner especially the one who does not show respect to Mohammad. The inside walls of the graves also presses with each other smashing the rib cage causing more pain and torture on the dead. In fact, the dead come to life inside the grave in order to experience pain and then beg the Prophet Mohammad for mercy. What happens in graves and the kind of punishment and torture a sinner suffers on his body points to the fact that the organization appears as fully cognizant of life after death. The horrific images of these lessons at once transfer listeners/readers imagination from life to a space of death and rupture people’s synchronicity of life. Some of the titles that deals with grave are:

Qabr ki Pehli Raat (First Night in the Grave), shown in Fig. 16

Qabr Khul Gai (The Grave Has Opened),

Qabr Walon ki 25 Hikayaat (25 Lessons of Grave),

Qabr ka Imtehan (The Test of the Grave),

Qabr ki Pukar (The Call of the Grave),

Azab-e-Qabr Kay Asbab (Reasons for the Horrors faced in the Grave)

Qabron ka Haal (The Situation of Graves)

Qabristan ki Ghaibi Awaz (The Unheard Voice of the Graveyard)

Qabr ka Garha (The Grave’s Pit)

Qabar ki Sarguzisht. (The Experiences of the Grave)

Qabar ka Sulook (The Grave’s Treatment)

Andarey Qabar Mey Kesay Rahu Ga Ya Rasool Allah (How Will I Survive Inside the Grave, O Messenger of Allah)

Qabr ki Tayyari (Preparation for Grave)

The description of death and modern technology are intimately tied with each other, and has become further intermeshed with the process of mass mediatization (Morris, 2000; Klima 2002). The intermixing of specters of dead with modern visual technologies problematizes the assume disjuncture between the sacred and profane. This entanglement of the religion and media is visible in Dawat-e-Islami’s efforts of elevating people to higher ethical life of Sunnah. From bodily disciplining via stickers to instilling fear through electronic forms, Dawat-e-Islami has deployed various media to propel people towards becoming Madani.

Sufi Shrines

In contrast to puritanical Deobandi and Wahhabi school, which prohibits visiting and praying on Sufi shrines, Dawat-e-Islami expresses reverence towards Sufis and Sufi shrines (mazaar/dargah). DI encourages people to venerate and celebrate Sufi urs (death anniversary) of aulia (pl. God’s friend) such as Khawja Nizam Uddin Chishti from India and Abdul Qadir Jilani from Iraq.11 The organization generally urges people to show reverence to all aulia and encourages them to pray through their wasila (representative/channel), since they believe that God will listen to a prayer if it comes through a Sufi mediatory. Since Sufis maintain such high status in DI’s belief system, the organization offers prescribed sets of rule for people visiting shrines. For instance, people visiting a shrine must always enter a premise facing the saint’s feet, maintain some distance from a grave, hold their hands up high for prayers, and must not leave with their back against the grave.12 These are instructions that every member must follow inside a shrine.

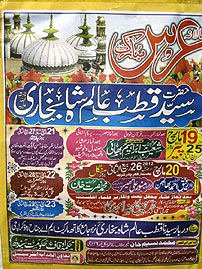

Fig. 15 Fig. 15 |

The poster in the figure 15 is the announcement for the Urs of local Sufi, Syed Qutb Alam Shah Bukhari. One can see these types of posters on the wall all over the city, especially in the old and congested marketplaces and neighborhoods. According to folklorist Jurgen Fremgen, Sufi posters demonstrate the bond of the mureed (disciple) with his pir (Sufi master) and express his personal religious identity.13 When I visited Syed Qutb Alam Shah Bukhari shrine, located in the middle of the marketplace, I met with a shrine’s caretaker, Munna Darbari, who told me that these Sufis are “allah kay piyare” (God’s beloved) and are ahl-e-nazar meaning these aulia can tell what is inside somebody’s heart. A firm believer in Sufi’s miraculous powers, Munna Darbari continued “These people left behind everything and Allah in return give them inamat (gift) which is in form of people coming to their dargah/shrine and revering them.” He added “through their [Sufi] sadqa (blessing) Allah ease our preshaniya (problems).

Not too far away from the shrine, a calligrapher and poster designer, Mubashir Alam, owns a shop, Nafees Printers, which publishes religious posters as seen in Fig. 15. “These kinds of posters are popular among religious circles,” says Mubashir Alam, “our four major customers are: 1) Ahle-Sunnat wal Jamat, 2) Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam (JUI), 3) Jamat-ut-Dawa, and 4) people who want it for Sufi Urs.” They buy 500-1000 posters at a time. During the interview, Mubashir Alam informs of the impact of digitization on hand work (haath ka kaam) of calligraphy. The calligraphic part of the poster has been reduced significantly because of the availability of computer technology. “A person with a good sense can tell if the poster is hand made or done by computer,” added Alam.

Fig. 16 |

Mubashir Alam’s anxiety arising from computerization of poster art was further confirmed when I encounter Dawat-e-Islami’s digitally illustrated images of Sufi shrines such as Abdullah Shah Ghazi from Karachi, as shown in the Figure 16. In fact, the organization designs 3D animations of various Sufi shrines such as the one seen on TV in which a naat khwan singing “Yeh shan hai mere Khwaja ki” (This is the glory of my Khwaja) in honor of Khwaja Moinuddin Chishti. While a naat khwan sings, 3D animations of the shrine are seen in the background and “transport” people to every corner of the premise. At times, real images of the shrine are interspersed in the video which makes it more difficult to differentiate between what is real and what is animated. DI is also active in producing 3D animations of revered religious sites such as Masjid-e-Nabwi. 3D graphics provide a more visual and dynamic interface for people to experience the inside view of some of these sites. The visuals transport the viewer to each and every corner of the site without being distracted or disrupted by the real world. It takes the viewer inside sacred shrines or places that are off-limits to the general public.

Fig. 17 |

A graphic designer also enjoys the liberty to manipulate anything such as the design of the building or the speed in which the image is travelling in order to offer an “authentic” experience. In Masjid-e-Nabwi’s animation, animators even embossed Dawat-e-Islami’s name on the mosque’s floor (which is not something that exists in reality). Thus the use of animation fully reflects the use of latest technology blurring the boundaries between the real and visceral and provides a sense of immediacy to the audience.

In the last decade or so, the emergence and spread of extremist religious groups has generated tensions and conflicts around Sufi practices, especially the frequenting of shrines. Islamic literalists, inspired by the conservative Wahhabi branch of Islam, declare mystical practices to be blasphemous and in need of eradication. Sufi Shrines have been bombed across Pakistan with number of pilgrims getting killed. The Fig. 17 is a poster by Sunni Itehad Council (a coalition of Sunni organizations) calling people for a “Long March” against the frequent bombings of major Sufi Shrines. Despite the violent efforts by both liberals and Wahhabi to stop people visiting shrines, Sufi practices continue to thrive among wide sections of the population across the country.

I.T. Majlis

Fig. 18 |

The DI’s information technology department commonly referred to as I.T. Majlis is the force behind the organization’s virtual revolution. Located inside Faizan-e-Madina, the I.T. Majlis comprises of 30 staff members who work in several areas: research and development, quality assurance, website, and multimedia. The Fig. 18 shows staff working in a small room of the I.T. Majlis located inside the Faizan-e-Madina. At times, however, volunteers also offer their technical skills.

Since DI’s website is the primary channel for presenting the organization to the outside world, most of the I.T activities are geared towards maintaining a dynamic web portal. From its first launch in 1995, the website has evolved into a virtual Faizan-e-Madina offering all the major services that the organization provides at its physical location. Easy-to-navigate and user-friendly, the website is available in three different languages: Urdu, English, and Arabic, for multiple audiences.

Fig. 19 |

The image of Medina appears on the website’s top banner while the Kaaba appears behind Medina, showing DI's passionate reverence for the city. In an effort to clearly disassociate itself from Islamic extremist groups, on the top of the website, the banner says, “A Global Non-political movement for the propagation of the Quran and Sunnah.” The rise of political Islam in Pakistan has forced “apolitical” religious groups to assert their image and profile as non-political and non-violent organizations. Moreover, the website streams the Madani channel live, and feeds updates via micro-blogging and social networking websites such as Twitter and Facebook to its followers.

The unique aspect of DI’s website is its ability to interact with the people. Via its website, a person can send its request to services such as Rohani Elaaj (Spiritual Treatment), Haatho Hath Kaat (Instant Spell Breaker), Haatho Hath Istikhara (Instant Divination), Become Mureed (disciple), and Dar-ul-Iftah Ahle Sunnat (Department to issue edicts). The volume of queries that the DI receives through these services are in thousands. For instance, via the website, DI received more than 20,000 queries per month for Rohani Elaaj (spiritual treatment) from all over the world. “We also receive a huge number of questions from people who are searching for answers in accordance with the Sunnah” informed the I.T caretaker or nigran, Shahid Butt during the interview. “Due to the increased volume and amount of time it takes, sometimes we stop taking new queries” said Butt. Although I have not been able to research the use of DI’s website outside Pakistan, it is evident from the number of queries receive that most of the users live abroad who do not have access to Faizan-e-Madina. Shahid Butt also confirmed in the interview that most of our users are from outside Pakistan who wants to stay connected with DI activities.

In addition to the website, I.T Majlis is actively engaged in software production, which are published frequently in forms of CDs and in form of online downloads available for free of cost. For instance, it is in process of creating a digital library from where patron can read or download a book. According to Shahid Butt, “digital library which is available on the website holds more than 200 books on different subjects.” In recent years, the I.T Majlis has become more technologically active and quickly scans and uploads any new material published by the organization’s publishing house, Maktub-ul-Madina. Originally written in Urdu, large numbers of these books are translated into more than 20 languages. The organization’s effort is to make these books available for free so that it can reach to mass audience. To makes these books available offline, DI also plans to launch a new software called Madina Library. “This software will be an in-house production. It has a search function and each electronic book is synchronized with the physical book. So if a person searches for Madina inside the software, it will give a page number which also matches with the page number on a physical book,” explains Butt. In future, Butt envisions launching an audio book service.

A few of the software such as Al-Quran, Fatawa Rizwiyya, and Auqat-e-Salat are already available on the website free of cost. Recently, DI has issued a latest version of AlQuran 2.0, which provides audio recitation of Quran in Urdu and English translation. The 30 volumes of Fatawa Rizwiyya is now available on a single CD. Auqat-e-Salat offers prayer timings for almost million locations, qibla (Mecca) direction, Islamic calendar, and Map. According to Shahid Butt, “we prefer to develop our own applications and software before we go and search in the market.” In future, the IT Majlis also envisions in starting an online one-on-one Madrassah-tul-Madina on their website. This service will offer Quran and Sunnah courses for people who have limited access to DI’s madrassahs.

Fig. 20 |

One important aspect of DI’s I.T Majlis is its use of information and communication technologies (ICT) in advancing organization’s cause. Increasingly, DI is also reaching mobile subscribers by providing them phone application such as Auqat-e-Salat. It makes it easier especially for people travelling in Madani Kafila to check prayer times and see Qibla direction in remote parts of Pakistan. However, the more popular DI product that is available to millions of mobile phone users are the ringtones. In recent years, people are switching to religious ringtones especially those that are derived from the devotional genre of naat. Slogans from Ilyas Qadri’s sermons are also used for ringtones. The huge panaflex banner listing phone codes for naat is pasted on the wall near the entrance of Faizan-e-Madina as shown in Fig. 20. A person can download the naat of their choice by merely dialing a code free of charge. “Initially, mobile phone companies were not in favor of hosting DI’s ringtones on their service menu” informs Shahid Butt, “we had to convince them until they finally agreed to our proposal.” We are also planning to start a web-based and mobile service of Madani Inamat,” (a booklet of self-disciplining that links to rewards) told Butt. “A person can fill out his Madani Inamat on his mobile phone. After entering the data in Madani Inamat, the software will automatically calculate the numbers and through a centralized submission process, the data will be entered in our database.” The web-based Madani Inamat will save the hassle of distributing and collecting the physical booklet and at the same time aim to effectively micro-manage people’s rituals.

Fig. 21 |

Given the large number of mobile phone users in the country, it has become imperative for DI to capture mobile markets in every way possible.14 I.T Majlis thus started marketing and selling memory card full with audio and video sermons and naat for mobile phone users. The Fig 21 shows a banner advertising memory cards, hanging on the wall near Maktub-ul-Madina. Shahid Butt explains that “During religious events we also set up tables with laptops at the entrance of Faizan-e-Madina and anybody can get sermons downloaded on their mobile phones free of charge.” “It depends on the Islamic calendar” continues Butt, “during the Hajj season we upload Hajj training courses on memory card.” During Rabi-ul-Awwal, the month of Prophet Mohammad’s birthday, people become interested in downloading naat on their mobile phones. What started out as a small publishing activity, DI has successfully expanded itself from conventional printing materials such as stickers and pamphlets, pasted and distributed in localities, to a more advance multimedia technology readily circulating in global mediascape.

Madani Channel:

As mentioned earlier, Dawat-e-Islami is the first religious organization to start its own television channel, Madani. This has been one of the most challenging steps for the organization and it took numerous considerations and many attempts at persuading different stakeholders including the founder of DI, Ilyas Qadri, to finally launch this channel. The challenge was not that there was a lack of money nor even a bureaucratic hurdle. Rather, it was that the launch of a television channel would open a new set of debate on the use of visuals which at the same time went against the organization’s fundamental principles and practices. As mentioned earlier, DI vehemently opposed the use of visual images which they had deemed anti-Islamic. This resistance is evident from the fact that DI’s members previously covered their faces as soon as video or a still camera tried to take their images. More importantly, launching a TV channel would mean that Ilyas Qadri’s face for the first time would appear to mass audience who had heard of the founder but had never seen him before.

DI sensed the growing role of TV channels in contemporary society. Because of television’s increasing significance and its effectiveness in spreading messages to far-flung areas, DI withdrew from its core belief of opposing TV and submitting to the demand of society and market. However, it took more effort to convince Ilyas Qadri to agree to an Islamic channel. Different edicts (fatwas) from prominent Islamic scholars were presented to Qadri that allowed the use of TV according to the principle of Islam. Finally, in 2008, DI launched its TV channel called Madani, which came as a surprise to people who were familiar with the organization’s opposition to visuals. DI was quick to justify its new venture by presenting an argument that “99 per cent homes own TV sets, which spreads evil (burai) in our society” and thus “the organization took the right step to start its own channel in order to bring people to the right path.”15 Furthermore and this an important aspect, according to the organization “sinners would benefit by merely seeing Ameer’s [Ilyas Qadri] face on the Madani channel because his face shines with divine light and righteousness”16 as shown in Fig. 22.

His sighting (deedar) bring numerous sawab (blessing) upon a viewer. Despite numerous justifications, Ilyas Qadri feels reluctant to fully accept the use of TV and the benefit it can offer. “The purpose of the channel is to send messages only to those houses which own TV,” proclaims Ilyas Qadri. “I have been against TV and I am still against TV” informed Ilyas Qadri.17 The resistance against TV is captured in this slogan: “Chor dey TV ko VCR ko – Ker dey razi rab ko sarkar ko.”18 Hence, Madani channel is only for people who already own TV set, which according to DI is owned by 99 per cent of households, and who waste their time in watching un-Islamic programs. In other terms, it is only one per cent of the population that has no access to Madani channel in the country.

Madani channel is equipped with the latest production technology comparable to any other TV channel in Pakistan. “We wish to bring Madani channel in every household” asserts Osama Attari who worked for national television, Geo. Attari decided to work for Madani because he felt that the channel is engaged in the faithful (deeni) work of promoting Islamic values. There are 250 staff members working for Madani channel. Since the channel is free of commercial advertisements, it is solely run on donations (atiyat). Madani channel is responsible for producing CDs and DVDs of sermons and naats as well. “We produce 5000 CDs in one time,” told Osama Attari, caretaker (nigran) of Madani channel. “If the demand is high then we end up producing more” continued Osama Attari.

Fig. 23 |

Madani Channel broadcast variety of programs to its viewers. More airtime, however, serve to bring sermons (bayan) of Ilyas Qadri and other senior presenter from Faizan-e-Madina. Often times, the organization broadcast sermons live on Madani channel in different countries. “Each program that we produce first assessed by our quality control team which is headed by a group of senior committee of scholars (shura) who check for un-Islamic content before it is broadcast” told Osama Attari. It also brings Madani Khabrein (news), which presents organization’s routine activities ranging from release of new study materials to flood relief campaign in Pakistani villages. The news boost DI’s increasing presence in non-Muslim communities in North America and Europe impressing people at home of its outreach program. A news broadcaster adorns traditional clothes, white shalwar qameez and green turban, and enters bare feet inside the news studio. In another widely presented show of Madani Mazakara, held in Faizan-e-Madina, a phone caller or an audience member presents his problem/question to Ilyas Qadri for possible solutions. For instance, on one occasion a phone caller, who was suffering from cancer, asks Ilyas Qadri to find a cure for his health. Upon hearing the case, Ilyas Qadri earnestly replied that “we will pray for your health and we will also mail taweezat (amulets) to your home address.” In addition, Ilyas Qadri told the caller to fill out the online form in spiritual cure (rohani ilaaj) section on DI’s website.

In an effort to reach a wider public, DI also host a cooking show, Aap ka Dastar Khawan, presented by a male chef. The show begins with a naat: dana dana meray huzoor ka hai, kia zamana meray huzoor ka hai” (Each grain belongs to my Prophet [Mohammad], what times were those of my Prophet). Then in light of the Quran a chef gives a short description of the main ingredients in the recipe. Since overwhelming majority of cooks in Pakistan are women, DI’s cooking shows attempt to primarily reach female viewers. During the phone interview with one of the female DI mureed, I was informed about the benefits that Madani channel offers to the people. “We learn more about our deen (faith) from Madani channel,” says Farhana Mehboob who has stopped watching all the entertainment channels five years ago in order to abide by religious principles. Farhana informed that there is no female host in Madani channel, in fact they are not even allowed to call in to the programs in which host take live phone calls from the viewers. When asked if it is permitted to watch male host on Madani channel, given the fact that DI strictly asserts gender segregation. Farhana replied, “nazar ki baat hai” (it is about gaze) referring to spiritual viewing and keeping one’s mind clean of immoral and sinful desires. She added further that females are also encouraged to keep their gaze down while “watching” Madani channel. “The important thing is to listen to the message and we can do that by keeping our gaze down,” says Farhana. The main benefit that Farhana pointed out is that people learn tariqa (method) of how to perform religious rituals such as namaz (prayers), reciting Quran in Arabic accent, etc. “Our buzrug (elders) only told us to pray five times a day but the TV [Madani channel] showed us how to perform,” informs Farhana. It is true that majority of the people watch religious channel for learning “proper” methods of performing rituals and everyday activities. Madani channel is at the forefront of offering these tariqa to the people who feels that they are unaware of right ways and guidelines and thus find TV channel as a source of learning.

In an another effort, DI also works to promote and spread its message to the deaf and the mute by presenting TV shows, especially sermons, in sign language. At the same time, the organization offers sign language classes to the mute and the deaf. One would notice in these programs that the TV show hosts, including Ilyas Qadri, never look in the camera and always keep their gaze on the book or on the floor. In standard TV programming where TV presenters directly look inside the camera to develop a direct connection with an audience, DI’s shows go against the conventional standards of TV show hosting. Moreover, the channel is commercial free and in place of advertisements, a serene naat couplet is introduced such as “Dawat-e-Islami nay duniya bhar mein dhoom machai hai” (Dawat-e-Islami has caused an uproar across the world). At times, the channel also uses 3D animation of Masjid Nabwi with sound of naat in the background, with clouds moving freely over the green dome. Thus the channel intermittently informs the viewers that “Remember that sound and visual of different scenes presented on Madani channel goes through editing.” On YouTube, Madani channel has more than 6,467 videos and more than 800 subscribers.

Conclusion:

Built on conservative Barelvi ideology and merchant capital, Dawat-e-Islami gained popularity amongst lower-classes in urban Pakistan. The iconic green turban of DI's followers, their echoing and reverberating naat khwani, their festive celebrations of Prophet Mohammad's birthday, and their bodily practices made the organization a unique phenomenon in Pakistan. It claims to promote Prophet Mohammad’s true teaching and his authentic lifestyle, Sunnah. Closely emulating its rival religious movement, Tablighi Jamat, in terms of organizational structure especially the practice of proselytizing, DI came into direct ideological conflict with literalist Islamic movements. At times, the tension between Barelvi and Deobandi ideologues would lead to violence. However, DI largely disassociated itself from militant Sunni groups including the organization’s offshoot, Sunni Tehrik. It claims to be peacefully advocating religious values through its complex media network, which ranges from stickers to multimedia in order to spread Sunnah prescriptions into each and every detail of life and spaces. Stickers serve as a technique through which a person’s every movement is regulated and thus embodied with religious coding.

Over the years, DI successfully introduced new ways of spreading its message to the public becoming the only religious movement with a television channel in the country. Initially against modern technology especially the television and cameras, DI has enthusiastically embraced innovative ways of reaching to the public. This does not mean that their ideological background is shifting from conservative to a more liberal worldview. It is precisely through the use of technology, that their conservative ideology is intensified and imposed. Nonetheless, Dawat-e-Islami is successfully transforming the ways in which belief and devotion are mediated in Pakistan's urban spaces.

Bibliography

Primary Sources (Dawat-e-Islami’s publication):

Al-Madina-tul-Ilmiyah. (2011). Vali se Nisbat ki Barkat

---.,(2011). Faizan-e-Mazarat-e-Aulia

---., (2011). Qabar mein anay wala Dost

---., (2006). Tarruf Amir-e-Ahle-Sunnat

---., (2006). TV aur Movie

---.,(2009). Madani Channel kay baray mein Ulema o Shakhsiyat kay Tasurrat (Vol.1-5).

---., (2008). Ibtaidai Halat: Tazkira Amir-e-Ahle-Sunnat Episode 2

---., (2008). Tazkira Amir-e-Ahle-Sunnat Episode 1.

Maktab-ul-Madina, (2005). Amir-e-Ahle-Sunnat kay TV kay baray mein Tasurrat.

---., (2005) Dawat-e-Islami ka Tarruf

Qadri, Ilyas. (2003). Qabar ka Imtehan

---.,(2010). Istanje ka Tarika

---., (2010). Qabar walo ki 25 Hikayat

---., (2007). TV ki Tabakaria

---.,(2006). Madani Inamat 72 Islami Bhaio kay liye

---., (2006). Madani Inamat 63 Islami Bheno kay liye

Interviews:

Munawwar Attari, October 16, 2011

Osama Attari, October 16, 2011

Shahid Butt, October 20, 2011

Mohammad Ikram Attari,October 20, 2011

Farhana Mehboob, March 09, 2012

Mubashir Alam, February 23, 2012

Munna Darbari, February 23, 2012

Multimedia:

Madani Channel

Qabar ki Pehli Raat

Dawat-e-Islami ki Jhalkia

Introduction of I.T Majlis

Secondary sources:

Ahmed, Khaled.Sunni Tehreek Suffers another Revenge Killing,. The Friday Times, Vol. XIII, No. 13 (May 25-31).

Eisenlohr, Patrick. (2006). “As Makkah is sweet and beloved, so is Madina: Islam, devotional genres, and electronic mediation in Mauritius.” American Ethnologist, 33(2), 230-245.

Frembgen Jürgen Wasim . “The Scorpion in Muslim Folklore,” Asian Folklore Studies. Vol. 63, No. 1 (2004), pp. 95-123

Gugler, Thomas. (2011) “Making Muslims Fit for Faiz (God’s Grace): Spiritual and Not-so-spiritual Transactions inside the Islamic Missionary Movement Dawat-e Islami.” Social Compass. Vol. 58 no. 3 339-345.

Klima, Alan. 2002. The Funeral Casino: Meditation, Massacre, and Exchange with the Dead in Thailand. Princeton University Press.

Mansoor, Javed.The New Militant,. The Herald, January 1992.

Metcalf, Barbara. D. (2009). Islam in South Asia in practice. Princeton University Press.

Morris, Rosalind C. 2000. In the place of origins: modernity and its mediums in northern Thailand. Duke University Press.

Nasr, Seyyed. Vali. R. (1994). The vanguard of the Islamic revolution: the Jamaʻat-i Islami of Pakistan. University of California Press.

1 I am thankful to Mariam Sabri and Zehra Sabri for proofreading the draft and for offering useful Urdu translation.

2 In recent years, religious phenomena especially the extremist currents in the country have attracted scholarly interest among the academic community. See Ahmad, Sadaf. Transforming Faith: The Story of Al-Huda and Islamic Revivalism Among Urban Pakistani Women. Syracuse University Press. Iqtidar, Humeira. (2011). Secularizing Islamists?: Jama’at-e-Islami and Jama'at-ud-Da'wa in Urban Pakistan. University of Chicago Press. Toor, Sadia. . The State of Islam: Culture And Cold War Politics In Pakistan. Pluto Press.

3 Al-Madina-tul-Ilmiyah. Tarruf Amir-e-Ahle-Sunnat (2006).

4 Al-Madina-tul-Ilmiyah. Ibtaidai Halat: Tazkira Amir-e-Ahle-Sunnat Episode 2

5 Al-Madina-tul-Ilmiyah . Tazkira Amir-e-Ahle-Sunnat Episode 1. 2008.

6 Barbara. D. Metcalf, Islam in South Asia in practice. (Princeton University Press: 2009).

7 Former political activists found religious practices such as of Dawat-e-Islami as a cover to protect themselves from the state’s onslaught against ethnic political groups like the MQM. On 26 July, 1997, the MQM finally changed the organization’s name from the Mohajir Qaumi Mahaz to the Muttahida Qaumi Mahaz (United National Movement), thereby broadening its appeal from representing only Mohajir interests to championing those of the oppressed classes in general, rejecting the ethnic and linguistic identity which had hitherto been central to it.

8 Javed, Mansoor. “The New Militant,” The Herald, January 1992.

9 Ahmed, Khaled. “Sunni Tehreek Suffers another Revenge Killing,” The Friday Times, Vol. XIII, No. 13 (May 25-31).

10 For detail account of Dawat-e-Islami’s international operation see Thomas Gugler, “Making Muslims Fit for Faiz (God’s Grace): Spiritual and Not-so-spiritual Transactions inside the Islamic Missionary Movement Dawat-e Islami.” Social Compass 2011). Vol. 58 no. 3 339-345.

11 Urs comes from an Arabic language literally meaning marriage, however in South Asia, the word is used for Sufi’s death anniversary implying a Sufi’s union with the God.

12 Al-Madina-tul-Ilmiyah. Faizan-e-Mazarat-e-Aulia. 2011.

13 Jurgen Wasim Frembgen. “Saints in Modern Devotional Poster-Portraits: Meanings and Uses of Popular Religious Folk Art in Pakistan” Anthropology and Aesthetics, No. 34 (Autumn, 1998), pp. 184-191.

14 Five foreign mobile phone companies have provided the entire country comprehensive network coverage (over 100 million subscribers).

15 Maktab-tul-Madina, Madani Channel kay baray mein Ulema o Shakhsiyat kay Tasurrat, 2009. Pg. 14.

16 Maktab-tul-Madina, Madani Channel kay baray mein Ulema o Shakhsiyat kay Tasurrat, 2009. Pg 15.

17 Maktab-ul-Madina, Amir-e-Ahle-Sunnat kay TV kay baray mein Tasurrat. (2005).

18 Maktab-ul-Madina, Maktab-ul-Madina, Amir-e-Ahle-Sunnat kay T V kay baray mein Tasurrat.