Entangled Images and the Corporeal Sensorium:

Shia religious iconography and ritual practice in the Deccan

Fiza Ishaq

The essay investigates the centrality of vision and its connection to the sensory body in religious practices of the Shia communities of Hyderabad and Bangalore. It documents digital practices involved in the production of imagery and its consumption during ritual practice. Through analysis of images and cyber ethnography it maps flows of Shia religious iconography, in order to understand the nature of image production in this age of digital reproduction. This study is based on ethnographic field research conducted in two phases. The first phase of research was conducted before Muharram in October 2010. The second phase of research was conducted during the first twelve days of Muharram in December 2010. The essay has been further updated based on information gathered during fieldwork in Hyderabad in October and November 2012 and more recently from April to July 2013. Some data gathered during cyber ethnography conducted from June 2012 to July 2013 has also been used for further contextualization of image flows and entanglements. In both cities, I have interviewed residents in Shia neighbourhoods, devotees, caretakers of ashurkhanas, clerics and artists about art making practices, the reception of devotional art and religious rituals. In order to observe devotees’ interaction with imagery in the context of ritual performance, I participated in religious gatherings, sermons and ashura processions. Data collected in Hyderabad and Bangalore has offered well for analysis of transcultural flows of imagery, particularly involving the use of new media technologies. This is because both cities have been at the forefront of information technology revolution in India and inhabitants have had easy access to computers and other equipment either through cyber cafes and printing presses or personal computers and their own printing shops. This has added a whole new dimension to the visual practices involved in a community’s everyday religious life, consequently the manner in which religious practice itself has been affected by transcultural visual vocabularies.

A brief history of the tragedy of Karbala

Hazrat Ali had two sons, Hasan (625-670) and Husain (626-680). After Hasan’s death, Husain received missives from Yazid’s subjects in Kufa (near Baghdad), to travel there, in order to lead the Muslim community in an uprising against the Caliph. The battle of Karbala began on the first day of the month of Muharram (680 AD), when Husain and his supporters were intercepted by Yazid’s army. The final battle occurred on the tenth day of Muharram, when all the men were massacred (except Husain’s son Zain al-Abedin), their heads taken as evidence of their death to Yazid’s court in Damascus along with Husain’s wives and female relatives.

In Islamic history, the Battle of Karbala has been a moment which consolidated the split between the two sects; Sunni and Shia. For the Shia community worldwide, it became the foundational moment, defining their identity as partisans and followers of Ali. Since then, Shia religious practice has incorporated intense expressions of grief for Prophet Muhammad’s family (Ahl al-Bayt) and the martyrs of Karbala. This moment of injustice is mourned and commemorated by community members throughout the year, particularly during Muharram and Safar by holding religious gatherings (majlis) and public processions (julus). The narrative of Karbala has influenced the development of aesthetic and ritual practices. For centuries, artists have written prose and poetry about the martyrs and also depicted the battle in the visual arts, rendering imaginary portraits of the Prophet and Imams along with narrative scenes of the tragedy.

I begin the analysis of Shia devotional art by briefly historicizing the artwork itself, tracing its origins to parda-dari practices of Qajar Iran and Mughal and Persian miniature paintings. In looking toward these historical art forms, I have attempted to demonstrate origins of contemporary Shia iconography as well as gain some insight into the transformation of motifs and styles of representations in Shia devotional art across time and space. Processes of exchange, appropriation and adaptation which began with the cosmopolitanism of Islam in the early centuries have facilitated the development of the art form into its present state.

The flow of contemporary Karbala imagery is mediated through pilgrimage and, increasingly so, the Internet. New media has played a central role in propagating flows of Shia devotional imagery and it has enabled new image-making practices. Contemporary digital practices when traced to the internet reveal the journey of the image which may travel back and forth creating entanglements effectively losing its originality and making it nearly impossible to find its source of origin. In this process, appropriation plays a central role. Digital practices and graphic design have created new scopic regimes similar in their aesthetics to film imagery and video games. In the process of editing appropriated images, designers effectively localize the image. Karbala imagery is a means of disseminating religious knowledge. It offers guidelines for moral and ethical behaviour to community members. At the same time, beliefs pertaining to religion and morality can impact the ways in which media is used and consumed by the community. Thus, the text that goes along with the imagery is determined in accordance with current religious ideologies. This makes Karbala imagery a tool, sounding out ethical behaviour and correct practices. It becomes a device to be used in the effort to avert the tide of ideologies that are brought from the Middle East.

Finally, I argue for a corporeal sensorium in which Karbala imagery has a performative dimension and the body functions as a living medium. In his essay titled Visual essentialism and the object of visual culture, Mieke Bal notes, “The act of looking is profoundly ‘impure’. First, sense-directed as it may be, hence, grounded in biology (but no more than all acts performed by humans), looking is inherently framed, framing, interpreting, affect-laden, cognitive and intellectual. Second, this impure quality is also likely to be applicable to other sense-based activities: listening, reading, tasting, smelling. This impurity makes such activities mutually permeable, so that listening and reading can also have visuality to them.[1] Thus, I highlight the broader sensory role of vision, and how it may be linked to bodily sensation by turing to the notion of “corpothetics”. The reference to the “performative dimension of artefacts” is made by Christopher Pinney in his work on image-worshipping practices in a village in Central India.[2] He derives this from the anthropological theory of art proposed by Alfred Gell, wherein Gell states, that instead of focusing on “symbolic communication” of an artwork, he places emphasis on its “agency, intention, causation, result, and transformation”.[3] Pinney terms this “performative productivity”, which indicates a deviation from the focus on symbolism and meaning of an artwork to individual/group actions involving visual imagery.[4] Corpothetics, the devotee’s “bodily engagement” with imagery or the “sensory embrace of images” [5] enables the devotee to connect with the historical moment of Karbala and arouses piety and grief within the viewer. The bodily performance of matam before the images and certain symbolic aspects of the image, which are used an aid to enable the devotee to visualize the tragedy afford Karbala imagery with a performative dimension. While visual narratives of Karbala are embedded in the urban environment, the body in its performance of matam, reflects the narrative of Karbala, it narrates the injustice of this historical moment, the suffering of the martyrs and how in martyrdom lay victory for Husain who fought for humanity.

Overview of Shia neighbourhoods in Hyderabad and Bangalore

This study was undertaken in two cities located in southern India on the Deccan Plateau; Hyderabad and Bangalore. While Hyderabad is located in the state of Andhra Pradesh, Bangalore is a part of Karnataka state. In India, Shia are a minority within a larger minority Muslim community.[6] Compared to that of Bangalore, the Shia community of Hyderabad is much larger. Before we go into detail, let us look, very briefly, at the cities where research was conducted;

The city of Hyderabad, established in 1591, was a princely state whose early rulers were notably Shia (Qutb Shahi dynasty 1518–1687). Under their patronage the city became known in the Deccan as the centre for observance of Shia religious and ritual practices. Qutb Shahis were succeeded by the Asaf Jahi dynasty (1724-1948) who were followers of Sunni Islam, but continued state patronage of Shia shrines and Muharram processions. Contemporary Hyderabad is comprised of the old city and the newer urban parts. The old city located on the banks of the river Musi, was where the foundation of the first city of Hyderabad was laid during the Qutb Shahi period. Today, the Shia population is mostly concentrated in the old city. A number of the earliest Shia shrines can also be found in this area.[7] These are both public and private shrines (some of them open to the public on certain days, occasions or upon request). This research project was mainly focused on the Old city of Hyderabad and its inhabitants. The residents here predominantly include middle and lower socio-economic classes. Several of them are shopkeepers and merchants with businesses located in the neighboring bazaars. Inhabitants who advanced their economic and social standing over time moved to parts of the city with more expensive housing for upper and middle class, such as Banjara Hills. Many have also migrated to other countries in the Middle East and the West. But, it is common for those who move out to visit the old city during Muharram. This indicates its value and importance as a site of Shia pilgrimage within India.

Bangalore was established by Kempe Gowda I (1510-70), it was a fort enclosed by an oval shaped mud-brick wall. Bangalore fort came under the authority of Hyder Ali (1761–82) in 1766. It was perhaps during this time that Shiism was introduced in the region. It is believed that he and his son and successor Tipu Sultan (1782–99) were followers of Shiism. Today, the area of Richmond Town around Johnson Market, also known as Arab Lines, and other neighbourhoods such as Anepalya and Neelsandra, are known to have a considerable Shia population.[8] During the colonial period, migrant horse traders and labourers arrived from Iran to serve the British government. Some of their descendents continue to live in Richmond town and the surrounding areas. Richmond town is more centrally located; Johnson market is located on the main Hosur road which connects to upper class areas such as Koramangla and commercial establishments such as M.G road and Brigade road. Johnson’s market was established when the area was part of the cantonment under colonial administration. This part of the city houses one of the oldest ashurkhana (Shia Shrine) in Bangalore, known as a Babul Hawaij. The church, St. Gregorios Orthodox Cathedral is also situated nearby. The streets surrounding the market are residential areas inhabited by upper, middle and lower income groups. Inhabitants are mostly Shia, but also non-Shia and non-Muslims, particularly Tamil Christians. Other Shia shrines, Babul Murad and the Irani ashurkhana, mainly meant for the Irani migrant community (largely comprising of students come from Iran to study in Bangalore and their families), Darbar-e-Hyderi, Darbar-e- Askari, as well as a large community hall Imamia Manzil are the religious structures and communal spaces that make it an area of central importance to the Shia community of Bangalore.

Residents of Neelsandra and Anepalya belong to low income groups. Neelsandra has one large community shrine and others are mostly private sometimes open to community members. The area has a central street (Bazaar Street) with a market, a mosque and temple and an adjoining maze of side streets lead to the community shrine and residential area. Anepalya is located adjoining Neelsandra.

Visual Narratives of Karbala: from paintings to digitally produced banners

There are several reasons for putting together this section, whose relevance may be contested and questioned by some readers. Digitally produced flex banners depicting the battle of Karbala began being consumed in about the last decade, from the turn of the century. Their consumption has steadily increased in this duration.

Some may consider this spurt in consumption of cheaply produced banners a phase and others might see it as a direct result of access to the internet and the proliferation of images one is faced with in everyday lives. However, this current move towards flood of consumption of flex banners emerges from a rich tradition of Karbala being depicted in other art forms and conveyed through various other media at different time periods and in different cultural contexts. By way of historicizing contemporary Karbala imagery, I aim to demonstrate that visual depictions of Karbala are not a 21st century phenomenon. But, that the visual has been central to Shia religious practice from several centuries ago. Secondly, flow of visual and material culture has occurred throughout the ages and transculturation is a process that has always existed.[9]

The aim of this section is to study how the scopic regime this gave rise to in the context of Shia ritual and religious practice, has evolved into contemporary times.

this section seeks to historicize current digital practices of making Karbala imagery. While a linear history of Karbala imagery from Mughal and Safavid period to the present will be a vast undertaking. By briefly charting the itineraries of Karbala imagery and analyzing iconography and symbolism, I try to show here how the imagery might have emerged from these historical art forms, how iconography may become a part of a community’s visual memory and how it has to evolve as a symbolic narrative in visual form.

Islamic miniature paintings

Miniature paintings have historically been a potent medium used to construct religious and political images which conveyed the patron’s worldview and agenda to the viewer. Artists employed visual symbolism to convey sovereignty and legitimacy of the ruler as well as to depict narratives of piety, spirituality and mysticism. This art form which began in mid-thirteenth century, thrived under the patronage of rulers in Persia, Central Asia and India. Islamic iconography depicting scenes from religious texts (hadiths) were often created as part of illuminated manuscripts. The earliest depictions of Prophet Muhammad can be traced to the thirteenth century eastern Islamic world.[10] The art form was introduced in India during the reign of the Mughals (1526-1858). The Mughal emperor Humayun (1530-1556) invited two artists from the court of the Safavid dynasty (1501–1736) in Persia to work at his court in Kabul and later brought them to India. Humayun’s son and successor Akbar (1556-1605) formed the imperial atelier and asked the Persian artists to instruct court painters in the Safavid tradition.[11] This was possibly one of the earliest instances when depiction of certain religious subjects and styles of illustrating sacred iconography travelled to the Mughal court in India. Miniature paintings during this period were primarily produced for wealthy patrons and elite groups of the royal court, but there are art historical accounts which state that there was also a popular form of miniatures produced for the general masses which Barbara Rossi (1998) terms “Bazaar Mughal,” “Popular Mughal,” and “folklorish miniature.” These were produced during the mid to late seventeenth century in “court centers for sale to a wider clientele, often in bazaars, or by village artisans emulating court traditions.”[12] It is possible that these older art forms inspired the production of extant popular art posters in India, particularly twentieth century posters of Sufi saints and Mughal kings and queens.[13]

Fig 01 Fig 01 |

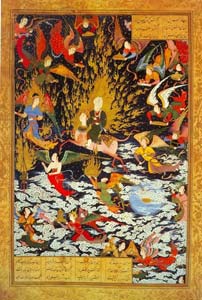

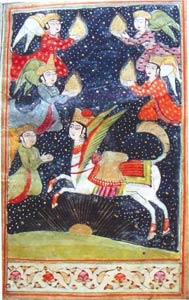

Buraq is the winged steed upon which Prophet Muhammad ascended to heaven. This journey on Buraq spans a single night (around the year 621) and is locally known as Shab-e-Mir’aj or the night of Mir’aj. It is celebrated by both Shia and Sunni alike. During my recent (2012-2013) field trips in Hyderabad and in Lucknow, I have come across paintings and popular posters of Buraq far more often in Hyderabad than in Lucknow. This I was told in Lucknow was because until recently, the motif of the steed was used to bridge the gap of Shia and Sunni religious practice and belief in the city. Due to Shia-Sunni conflicts now it is rare to come across any visual depictions of the Buraq in imambaras (shrines) of Lucknow. Mir’aj is a didactic tale, which has been presented in religious texts, as not merely a physical but an essentially spiritual journey of the Prophet across the seven heavens. In miniature paintings the Prophet has been depicted with characters such as the angel Gabriel, al-Buraq and sometimes several other angels (Figure 01). Artists have used symbolism in order to represent each protagonist in Mi’raj paintings.

A miniature illustration of the Prophet’s Mir’aj can be seen in Figure 01, it is taken from the Khamsa of Nizami, created for Shah Tashmasp I (1514 –76), the ruler of Iran in 1539-43. In this painting, the Prophet with his face veiled appears at the very centre riding Buraq. The sacred flame of prophethood is illustrated behind his form. The steed is depicted with a human head and its facial features are distinctly feminine. Its head appears graced with a golden crown, it wears an earring and has a bejewelled collar around its neck. Another important figure in the painting is the angel Gabriel, who appears on left-hand side center of the painting. His figure is distinguished by the other angels by attributing him with the divine flame.

Fig. 02 Fig. 02 |

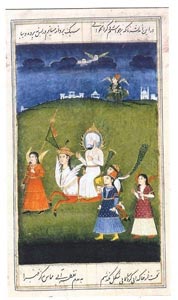

The next painting (Figure 02), was part of a Divan (compendium of poems) from eighteenth century Oudh (present day Lucknow) in India. In this image, the central figure of the Prophet seated on Buraq is shown wearing a white turban and veil, with a golden halo around his head. Buraq again depicted as a woman but with long hair and distinctly Mughal head gear with a plume at the center and Indian jewellery. A remarkable feature is the dark red bindi (a dot, which is forehead decoration worn in South Asia) on its forehead, further Indianizing – if not even Hindu-izing - her appearance. Another noteworthy feature is its tail which is made of peacock feathers. These feathers are often used in Sufi dargahs in the subcontinent and may be associated with mysticism. Finally, her wings are shown as emerging gracefully from her chest. The Prophet is lead by an angel carrying a green flag representing Islam. Following the main protagonists are three other figures: the woman dressed in blue wearing a red Turkish cap may be a houri.[14] The Angel Gabriel appears in the background. His larger physical appearance and placement in the painting above the earth and on the horizon indicate his importance. The scene in this painting is portrayed on land, depicting the beginning of the Prophet’s journey. The entourage of the Prophet appears to be moving at the base of a hill. While, at the top of the hill, several white buildings are depicted. These buildings may be palaces and the building with the minarets and dome in white is perhaps the Taj Mahal or a mosque. This is another remarkable aspect of the painting, the scene is depicted as though unfolding in India. This kind of symbolic territorialisation of the Mi’raj also appears in later chromolithographs (Figure 04).

Fig 03 |

Fig 04 |

Chromolithographs were initially produced in India by printing presses such as Raja Ravi Verma and S.S. Brijbasi, circulated under the separate category of “Muslim posters.” These were designed specifically to appeal to the popular tastes of Indian Muslim consumers. Their production continues until today. In figure 04 symbolism employed by the artist serves as an indicator of religious identity. The crescent moon, Taj Mahal and the mosque in the background are symbols utilized to provide an Islamic identity to the image. The use of motifs such as the Taj Mahal invokes the Mughal era and an Indo-Persian past.[15] This is done to appeal to an Indian Muslim viewer. In South Asia, the Muslim devotee inhabits “two worlds” - the Indian and the Islamic[16], Finbarr Barry Flood characterizes this as the “dialectical nature of Indian Islamic identity, (the double movement).”[17] By saying this he does not imply the deterritorialization of identity, but that there is negotiation “between the local and the translocal,” in everyday lived experience. He refers to the Indian Muslim being connected to a wider imagined Islamic community, while maintaining their nationalist identity. Indian Muslims while maintaining links to the Middle Eastern Islamic world,[18] through pilgrimage and by keeping abreast of and espousing religious ideologies advocated by clerics from this region. Simultaneously, they maintain their identity as Indians. Flows of Islamic ideologies, beliefs and practices are shaped by Indian and local, regional culture. This process of negotiating with trancultural flows can create tensions, but flows are also accommodated and adapted, when certain practices and beliefs are localized and accepted, while others are contested and/or discarded.

In Bangalore and Hyderabad, the Shia communities have maintained their identity through the practice of rituals such as pilgrimage (ziyarath) and the holding of religious gatherings (majlis), public processions

(julus) and performing self-flagellation (matam). But, their practice of Islam, and in this instance Shia Islam in the subcontinent, has also undergone the dynamic process of translation. Translation has resulted

in the formation of a religious practice unique to Shia communities belonging to the Indian subcontinent, which is also configured by regional culture and history of the community in their particular region, thus consolidating their

identities as Indian Muslims. Transculturation in this case has been determined by several factors such as; Indian Muslim links to other Islamic worlds, social status, personal histories of migration and genealogy. The consumption

of imagery and practice of rituals have been directed by religious beliefs and clerical regulations. This gave rise to a long standing debate concerning the communties’ idea of what they have termed and define as traditional and

authentic religious practice.

Nevertheless, there have been simultaneous efforts to keep up with the “ideal of the umma,” [19] which refers to ethical behaviour of a Muslim as ordained by hadiths. This is reflected in the composition

of popular Karbala iconography, as it assembles an array of symbols each carrying meaning in relation to memory of an essentially Islamic tragedy for the devotee, at the same time it is meant to shape the devotees identity as Shia,

being a member of the Shia community, as well as an Indian Muslim, simultaneously, a member of the larger community of Muslims residing in the subcontinent. The imagery is further localized by the use of recognizable architectural

monuments, connecting it to place and homeland, hence appealing to their nationalist identities as Indian citizens.

Fig 05 |

Aesthetic similarities between Buraq and Kamadhenu (Figure 05) have also been noted by various scholars studying popular culture in South Asia. Kamadhenu is known as the “wish fulfilling cow” from Hindu mythology.[20] It has been noted that imagery of Buraq draws upon representations of Kamadhenu.[21] However, Freitag suggests that it is possible that the twentieth-century representations of the figure of Kamadhenu were inspired by the depictions of Buraq, as it (Kamadhenu) was used by Hindu fundamentalists to promote their idea of religious nationalism.[22] Patricia Uberoi has noted that the cow was used as a “unique rallying symbol for Hindu ‘religious nationalism’ through the colonial and postcolonial periods.”[23] Similarities between the two symbolic representations become evident in their female form and adornments, the flowing hair and that both are represented as winged creatures.

A more recent depiction of Buraq (Figure 06) has been created by Bangalore-based artist Akhtar Alavi. He

has used an image of Buraq found on the internet which was originally created by Muharraqi Studios, a Bahrain based design firm. This was combined with other images to create a collage-like poster in which

Buraq appears at the center framed by images of holy shrines on either side. This twenty first century multimedia creation has transnational and predominantly religious appeal, as it lacks the use of motifs that root the

image in the Indian or any other nationalistic context. Without the text and images of Muslim shrines, the image of the steed could be any mythological creature with no marking for it to be identified with any particular culture or

religious tradition. However, the artist provides text in English with an account of the event of the Prophet’s ascension to heaven (Mir’aj) and Quranic verses. The text anchors the images and explains it the viewer while

the collage enables the non-literate viewer to connect the image of the steed to images of the holy shrines of Islam and comprehend its reference to the Mir’aj. Hence, this construction roots Buraq in the Middle

Eastern world of Islam, in order to create its (Buraq) link to the Prophet and to the holy event Mir’aj which occurred in that region. The holy sites framing the representation of the steed lends it a sacred aura.

Buraq carries symbolic meaning for the devotee. This analysis of the motif explicates the ways in which changes have occurred in its visual depiction, keeping in correlation with developments in societies’ politics,

ideologies and technologies of different cultural contexts and time periods. By being in constant motion, the motif has survived. It has made a place in the visual memory of a community, whether in use by the community or not. By

being reconfigured in accordance with the times, it has endured. [24]

Coffeehouse paintings

Coffeehouse painting was an art form that emerged in Iran during the Qajar period (1794 -1925). These were narrative paintings were predominantly utilized to present imagined depictions of Karbala and Shiite martyrology to devotees, who largely constituted the middle and lower classes in Qajar Iran. I suggest that contemporary devotional posters produced in present-day Shia communities of Bangalore and Hyderabad have been influenced by this art form. This section traces the development of early coffeehouse paintings to popular Shia devotional imagery produced in the Middle East. In Iran, the rituals of mourning such as holding public processions and recounting the tragedy of Karbala in enclosed gatherings gave way to what Chelkowski describes as “the only indigenous drama in the world of Islam”, known as ta’ziya-khani and also shabih-khani.[25] Initially, they were portable paintings known as shamayel or parda and were used when narrating the tragedy of Karbala or while enacting it before an audience. This ritual of presenting a visual and verbal narrative to an audience was known as shamayel-gardani or parda-dari. This was performed by one man known as parda-dar (storyteller) who would go from place to place, hang the painting and sing and/or recite the story during the Qajar era. The ritual enactment of Karbala graduated from street corners, to courtyards of caravanserais and then to theatrical plays performed in specially constructed buildings known as tekiya and huseiniya. Later, they came to be employed as decorative wall hangings and as murals in theatres, where they served as backdrops to theatrical enactments of the tragedy of Karbala.

As this practice developed, paintings began to be commissioned to decorate homes of the elite. Furthermore, a courtly “parda” form of painting for the royalty was developed. It was more refined and employed European techniques of perspective. In this parda-like painting, the colouring and mood of the painting were made less violent, more restrained and the characters appeared “princely and stately.” They came to be painted as murals on walls of palaces and shrines. I suggest that as these paintings evolved they diverged; on the one hand they formed into styles to be consumed by the elite and on the other hand, with access to modern technology in the twentieth century they inspired popular devotional posters. Although, the practice of parda-dari may have declined over time; the subsequent production of popular posters ensured that these powerful images continued to available to the middle and lower socio-economic classes.

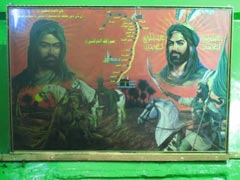

Fig. 07 |

The image (Figure 07) is one of the earliest examples of typical coffeehouse paintings produced in the late Qajar period. Although, not much information is given about the protagonists in the image, the iconography suggests that these are (from left to right) Abbas, Ali Akbar, Husain on his horse Zuljanah, holding the sword Zulfiqar and the enemy Yazid. There is also a smaller image of a woman appearing between Abbas and Ali Akbar - she is most likely Husain’s sister Bibi Zainab. Early coffeehouse paintings have been referred to as naïve, primitive and folk by scholars and art critics.[26] They were also considered as crude and lacking finesse of miniature paintings by the elite and upper classes. This indicates the distinction drawn between high and low (or popular) culture in Qajar society. This was perhaps due to their reception being in a vernacular context,[27] since their primary use was functional, as an aid to storytelling and for theatrical enactments, their aesthetic value became secondary. According to Diba, it was also the first time in the history of Persian painting that representations of religious figures were being painted for public consumption which challenged clerical views on figural representation in Islam. This was also the time when figural painting was flourishing in the royal courts and the European technique of perspective and painting with oils had been introduced.[28] Therefore, coffeehouse paintings were considered to be a part of popular religious practice in Iran, since they were not hung discretely in drawing rooms of elite homes or more flamboyantly in the audience hall of a palace.

In their later form as “refined” murals, these paintings were displayed in palaces and upper class homes; this reveals that they were desirable to the dominant classes as well. Their desirability was to be found in the visual representation of religious subject matter, the Battle of Karbala. Perhaps, it may have also been fashionable to display a Karbala mural in homes of the Qajar era elites, as a sign of their ability to afford such a work of art. For the aristocracy, it was perhaps a means of linking them to the historical, spiritual world of Shia Islam, serving as a means to assert their sovereignty and extend their power and authority to the realm of religion.

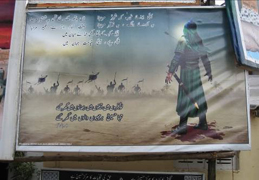

Fig. 08 |

Figure 08 is a popular devotional poster I found displayed at the ashurkhana Hazrat Abbas in Hyderabad. I was told by the caretaker that it was brought from either Iraq or Iran, where it was produced. A collage with a combination of portraits, a map and scenes of Karbala makes up this poster giving it a temporal depth. The two portraits are imaginary depictions of Husain (left) and Abbas (right) wearing green headdresses. Abbas who is often described in hadiths as a ferocious warrior is also shown on horseback, holding a green flag in hand and a sword in the other. The subsequent scene portrays his death in the arms of a mournful Husain. The background here symbolically shows the sun setting over the desert of Karbala, implying death. The map depicted at the centre in the poster traces the martyrs’ journey from Mecca to Karbala. Towns and cities that are located on the route are marked and labelled. It is a means for the viewer to situate Karbala, perhaps even imagine the length of the journey and hardships faced by the martyrs. It also provides the viewer with a sense of the sacred sites located in the Middle East, as it marks important places of pilgrimage; Mecca, Medina and Karbala, providing a small image of each to go with the labels. The flow of such imagery from the Middle East to Bangalore and Hyderabad creates connections between Shia communities. They become linked through a shared repertoire of symbolic visual representations which embody religious belief. This connection also becomes defined by reciprocal religious ideologies and spirituality, in the process becoming an acknowledgement of shared history and memory of the tragedy.

While modes of production have changed the imagery retains certain subjects of central importance to Shiite theology. In terms of their presentation to the viewer, there are some similarities between the coffeehouse paintings and contemporary posters produced in the Middle East and those currently produced in Bangalore and Hyderabad. Firstly, their large scale depictions of events from Karbala take on the form of a visual narrative. Secondly, they utilize multiple layers of imagery along with text. The use of both imagery and text ensures that the message about the tragedy is conveyed in all its clarity to the viewer. Here the text is used as a tool for explanation to the viewer and for its dissemination. The representation of the martyrs remains the same, although much sharper with the use of new technology. However, they continue to appear in similar headdress in green, bearded and with a direct gaze toward the viewer. The use of symbolic representations such as the sword (Zulfiqar), doves, Husain’s horse (Zuljanah) is also consistent. One of the significant functions of early coffeehouse paintings was to serve a didactic purpose. This has been continued in contemporary imagery, particularly in imagery produced in Bangalore and Hyderabad (as will be discussed in greater detail in the next section)

Karbala imagery in the age of digital reproduction

Fig. 09 |

Figure 09 is a religious poster which captures a moment in the deserts of Karbala before the battle occurred. It depicts Imam Husain’s caravan with his family and companions as he traveled from Medina to Kufa. The poster was shown to me by Akhtar Alavi, when I met him on the second day of Muharram in December 2012. He works as a graphics designer from his house in Bangalore. Among other things, he sometimes designs and sometimes prints from the net such image depicting Karbala and other religious visuals, such as calligraphy. He makes banners, posters, postcards and even prints them on calendars designed by him. This particular poster was printed on thick A3 size paper, which cost him about fifteen rupees or less if printed in large number of copies. This was one of about fifteen to twenty designs he had brought along. There were a few more sheets with post card size designs, which served as a catalog. These were meant as samples for a buyer, who would then choose from the many images and order large size banners to be printed. All the posters were digital prints and many of them had merely been downloaded from websites, some of these were free wall papers provided by religious websites, as I was to discover much later.

In recent years, the internet has become a medium through which the flow and exchange of vast amounts of information is mobilized. In Hyderabad and in Bangalore, local artists create and sell popular Karbala imagery for display in the streets and shrines during Muharram. For designers and artists, particularly the ones who were a part of this study, the internet is an immense resource for images, through which they have access to devotional art produced and uploaded on Iranian, Pakistani, Iraqi and other websites. Images are easily available through online search engines which have made it easier for designers as well as non-professionals to appropriate graphic images of Karbala, as well as stock photography. This practice has engendered new scopic regimes that present the narrative of Karbala in graphic detail. These digital reproductions some of them are so commonly available on the internet on more than one side and show up in more than one city, so that their proliferation creates entanglements. (see discussion of figures 10,11,12)

Artists such as Alavi (Bangalore), Mehdi (Hyderabad) and others, re-work downloaded images using Photoshop and other graphic design software and adapt them to the consumers’ requirements by adding text or adding other images to fashion an entirely new image or poster. Sometimes both consumers and designers download high resolution images using search engines like Google.com. At times these images are printed and used in their original form and design. On other occasions, the images are altered, artistic elements are added and even removed, such as text in foreign language. Sometimes, the fire of the burning tents does not seem bright enough for a large size banner, so the colour may be intensified. If the images does not show any blood on the ground, it may easily be added using Corel Draw or Photoshop. Several copies of these downloaded images are printed at local printing presses, in varying sizes and used as popular poster art. They are bought by consumers, who then either display it in their homes and ashurkhanas, or distribute and gift it to family and friends. Consumers who own businesses might order calendars or postcards to be printed with the names and logos of their company. This is then distributed among business associates.

Artists, designers and non-professionals, who are merely internet users, function as social agents facilitating transcultural flows that result in the reproduction and spread of digital graphics. This process has introduced new visual vocabularies of Karbala to community members. At the same time it has joined them to a larger community of Shia who understand, consume and share in a similar scopic regime. Most of the designers I have met with until 2013, have claimed that the banners and posters created by them are either taken by them or by their consumers to other cities of India, even to others countries in the west as well as the Middle East. Such mobility of the art work creates networks of flow, at times taking a reproduced image back to its site of origin, creating further entanglements. The artists Akhtar Alavi travels to other Indian cities; particularly to Lucknow, Hyderabad, Mumbai and Calcutta. He takes with him a CD of his art work to print posters and banners on location, which are then sold and distribution among members of the Shia community. Not only does he monetarily profit from his travel, it brings him in contact with new people whom he might gift a small postcard. In this manner a new acquaintance might even become a future customer.

In Hyderabad, due to the large Shia population, the production of Karbala imagery is a local cultural industry. There are professional and non-professional designers such as Bright Ads, Universal Ads, Deccan Digitals as well as individual artists such as Mehdi and Nisar. More often younger members of the community who are computer savvy design such devotional art by themselves for circulation within the community. Since the 1960s, Hyderabad has seen an increase in the migration of professionals and labourers to the Middle East and to western countries for employment. Karen Leonard has authored a well researched comparative study of Hyderabadi (people of Hyderabad) living in Pakistan, the west and in Gulf countries.[29] Hyderabadi migrants usually return to the city for the two months and eight days of the observance of Muharram. They often buy devotional art and artefacts such as alams, as well as banners both printed and handmade to take back to their adopted homes. In this manner, the work of art circulates to other parts of the world.

Flows and entanglements of Karbala imagery

Fig. 10 |

A poster and a cloth banner displayed on another sabeel in Hyderabad can be seen in Figure 10. The banner was designed by Zest Creations, a career consultancy. The cloth banner in black and white proclaims “Ya Husain.” The poster above it has been designed in three parts; at the very top the text states, “Karbala, when the skies wept blood.” The use of dark colours and large font for the title, which is followed by a sub-title, evoke the layout of a film poster. On the left-hand side is an image representation of Husain’s nephew Ali Akbar facing Yazid’s army in the battle field of Karbala. The image on the right hand side of the poster depicts the sky at dusk streaked with blood and Husain’s horse Zuljanah with its head mournfully lowered. The dramatic style of representation of the battle derives from contemporary film imagery and is reminiscent of posters designed for films about war, particularly pertaining to medieval history. Beneath a large title proclaiming Karbala, with what appears to be subtitle ‘when the skies wept blood’, there Ali Akbar’s name appears like a rolling credit. This along with the figure of Ali Akbar is depicted in the foreground as though he were the main protagonist. His vivid figure in full battle gear is placed at an angle to show light radiating from his face and blood can be seen at his feet, these features are used to gain the devotee’s attention. The imagery is a combination of stock photography (picture of the horse) and what may have been appropriated from Middle Eastern popular religious imagery in terms of style of depicting the martyr, while the refined look of the poster draws from film imagery. This reveals the influence of flows from various sources in the construction of contemporary Karbala imagery, at the same it suggests that stock images that do not necessarily belong to the genre of Shia devotional art are appropriated and adapted using specific features (like depicting a desert in the background or the sky streaked with blood) to acclimatize it to the religious context. Such digital images represent the past in a far more realistic, almost photograph-like manner.

Fig. 11 |

Figure 11 was designed by Bangalore based artist Akhtar Alavi and displayed in the courtyard of Agha sahab’s ashurkhana, along with the images discussed in the next section( figure 13). It is a similar Ali Akbar poster as figure 10. However, both the posters have been altered by their designers. In my search for the original I started looking at images on the internet, by searching Google Images for Ali Akbar. The image immediately showed up, it took me to a German website Vebidoo.de. The image was posted by user on photobucket.com. But, my quest was to find the original designer of this image. Google Images offers two useful options once the image is clicked on, one can opt to look for “more sizes” of the same image or “search by image.” Once I clicked on “more sizes”, I was provided with nearly fifty of the exact same images as figure 12.

Fig. 12 |

As one zooms into the text of figure 12, beneath Ali Akbar, the designers name is given as Karbala Style. Except

about four images, all the nearly fifty images that turned up in my search showed the name of the designer as Karbala Style and this same image had been posted on fifty different websites across the world. A quick search for Karbala

Style on Google.com took me to the website Deviantart.com. The image had been posted in a size large enough to be printed. The website has for several years been showcasing various art form from digital art, to photography and

traditional art forms. A user can make an account and upload images of his/her work which is then displayed for anyone to see. Beneath the image of Ali Akbar on Karbala Style’s account, the following was clearly stated ©2008-2013

!karbala-style, making him/her its original designer. However, this did not stop many from using it in their own work or posting it on other websites. Due to the large numbers of same image as figure 12 being found in my search,

with the signature of the designer, I concluded that Karbala Style was its creator. But, most such images on the internet come without the artists or designers signature. In such a case, a proliferation of the same image on several

websites makes it nearly impossible to find the original source. This is a clear example of flows and resulting entanglements.

The changes that were made to the image by designers in Hyderabad and Bangalore show in what ways an image might be altered as it journeys. In figure 10, other images had been added alongside it, and the original designer’s

signature had been removed. In figure 11, the whole text of the original image including the designer’s signature was removed. In its place, Alavi had added an elegy written by the poet Mir Anees. While in figure 10 and 12, the

image is meant to be of Husain’s son Ali Akbar, in figure 11, the elegy used by Alavi relates the image to Husain. The elegy refers to the time Husain went to face Yazid’s army and then returned bleeding, pierced by the enemy’s

arrows. This explains the shifting function of the imagery as it flows from one context, place or country to another. The reception of devotional imagery in the ritual context then differs from place to place and region to region.

As a difference in the range of religious knowledge emerges, mobility of images fostered by various media result in the creation of a “third product” which continues to be connected to and entangled with the sites of appropriation

and circulation.

The notion of appropriation has emerged as central to this kind of art-making and design practice. Here I will examine the nature of appropriation and how the next step alteration becomes a practice of localization in the making of

these banners. Appropriation has been defined as the “borrowing,” “copying” or “stealing” of something; “the action of taking something for one's own use, typically without the owner's permission.” Appropriation in artistic

practice has been defined as the borrowing of elements in the creation of a new work of art.[30] It is the technique of reworking images or objects from taken from various sources and using them in one's own work. In

western history of art-making, appropriation has been a well-known practice which began in the era of Cubism (1912) and was seen in the works of Picasso and Georges Braque. A most notable work of appropriation was French artist

Marcel Duchamp’s Urinal in 1915. Appropriation art, became a common term used by artists in the 1980s. This art form raised questions about issues such as originality, authenticity and copyright in works of art.

During the making of Karbala imagery, once an image has been selected and downloaded the purpose of its use is the next consideration. What alterations have to be made to the image is decided by the designer, in accordance with the

instructions of the customer. Banners are usually orders by customers for personal sabeel, majlis or merely to be displayed inside or outside an ashurkhana. Customers not only include lay persona, but also clerics

and care takers of ashurkhanas, Alterations made could include additions of text in Urdu, English and Arabic or changes made to the form, colour and other aesthetic aspects of the image. Text is important and nearly always

present on the banner along with the image. The text might be a couplet, a few lines from a marsiya of a well known poet such as Mir Anees or Mirza Dabeer, it could include verses from the Quran, at the same time it can

include statements, which can be read as interpretation of Quranic verses and hadith.

What the banner states and represents through its imagery can be understood as a practice of localization of religious practice through visuality. As certain ideologies and hadiths that elders of the community and the

ulema (religious leaders) promote become incorporated as text with appropriate images in the poster, making Karbala imagery an instrument, an apparatus and a means in the production of local subjects. Not only do the

banners communicate religious beliefs and ideologies of local groups, but in the process of alteration, the image itself becomes localized and hence transcultured. In his book,

Modernity at large: cultural dimensions of globalization, Arjun Appadurai describes the “spatial production of locality,” in reference to architectural structures. He states, “Locality is materially produced.”

[31] I propose, that Karbala imagery may be used by designers, artists and governing members of the Shia community in Hyderabad and Bangalore to produce and construct, as well as to maintain local beliefs and

“traditional” rituals pertaining to Shiism. By this I mean, that the imagery created advocates locally generated ideologies and practices of Islam which are described as “traditional” by community members. Adaptations, such as

the use of local language are meant to create, propagate and maintain an Indian, Shia and Muslim identity. Through its reconfiguration Karbala imagery produced in the subcontinent becomes translated for Indian viewer and devotee. At

the same time, certain images are used to link and associate the local Shia community to the Middle East, the place of Islam’s origin, home to its holy sites of pilgrimage.

Practices of display and looking

Every year during Muharram, Habib Agha who lives in Bangalore, in his ancestral home near Johnson’s Market, decorates his courtyard and the adjoining street with banners depicting Karbala (Figure 13). For nearly thirty years now, Agha sahab (as he is addressed by the local community) has continued this custom. Initially, he would commission calligraphers and local artists who made oil paintings. However, with the arrival of computer technology he has turned to digital prints. For the past fifteen years, the artist and designer Akhtar Alavi has been designing Karbala imagery for him. Alavi usually brings a number of sample images before Muharram for Agha sahab to select from. Sometimes, Agha sahab makes a request for a poster design with a particular figure or motif, which is then found on the internet or in a magazine and used to create the poster. Once the images are selected, the posters designed and printed, he spends several days “curating” the display and supervising their placement in his courtyard, private shrine and the street. This case study reveals contemporary forms of patronage of the arts within the community. Through his interest in the arts and by promoting the work of Alavi and some other artists, Agha sahab is well-known for his displays of Karbala imagery. He is also revered as an influential member of the Shia community in Bangalore. His ashurkhana is centrally located and the ashura julus begins from near his house.

Fig. 13 |

This picture (Figure 13) was taken during Muharram 2009 in Bangalore, as the courtyard of Agha

sahab’s house was being prepared for a religious gathering (majlis) later in the evening. In the picture, the first banner (in the first row, Left to Right) captures the moment of Husain’s martyrdom. The image

depicts his wounded body and his horse Zuljanah. It is a copy of a well known Iranian painting that has been reproduced as a banner with Urdu text. The title on the banner proclaims the name of Husain. At the bottom of the

poster Urdu text is translated into English, it reads, “O Husain! The manifestation of thy pristine light shall never, ever be silenced.” The adjoining banner is an imaginary scene depicting Husain voicing his grievances about his

followers into a well. It is titled Fariyadi Ali (meaning Ali’s supplication). The image is an art work that was copied from an Iranian magazine. The artist had this printed in large size and translated the Persian poem

about Ali into Urdu the local language. The poem reads: “It is sad that Ali has no supporter and no companion other than a well…there is no one as lonely as him.”[32] Such imagery may be considered ekphrastic, as

it offers a verbal description in the form of poetry of the scene portrayed.

The next poster displayed on the right hand side corner of the image is crucial to our understanding of transculturation of the Karbala narrative. The quotes are taken from hadiths that indicate Husain intended to travel to

India. The first line in the banner has a quote from Prophet Muhammad, “I get cool breezes from the side of Hind.”[33] The next line quotes Imam Ali, “The land where books were first written and from where wisdom and

knowledge sprang is India.” In an essay titled Is there anything called ‘Muslim Folklore’?, Rahmat Tarikere[34] writes about Muharram celebrations held in Mudgal (Raichur District, Karnataka); the

participants[35], he says, believe that two brothers Hasan and Husain migrated from Arabia to Mudgal. The importance of this story and the quotes from the banner are examples of how the narrative of Karbala was adapted to

this Indian context and came to have different meanings for diverse groups. Perhaps in the contact zone of the street and the shrine, narratives such as this are required to establish roots and to express the Muslim and the Indian

identity of the devotee. Furthermore, these narratives would become essential in order to construct the identity of the devotee in the contact zone, that is, their identity as the Indian Muslim stressing on both the nationalist and

religious aspects.

The banners in the second row are imaginary scenes of Karbala. The first banner depicts the death of Hazrat Abbas he is held by Husain and Bibi Zainab stands along side, with Zuljanah in the background. The adjoining banner

depicts the death of Ali Akbar (son of Hasan), who is held by Husain. His army is illustrated at the edge of the banner. The third banner represents Hazrat Ali in a red cloak, with the sword Zulfiqar placed in the foreground. Women

wearing veils and headscarves can be seen seated waiting for the evening’s majlis (religious gathering) to begin. This massive arrangement of Karbala imagery was to form a backdrop to the ritual of majlis known as

shaam-e-gharibaan which was to take place late in the evening on the day of Ashura. The posters covered all the four walls of the courtyard, and many were also displayed outside the gate, in the streets.

When asked about the reason for Agha sahab’s extensive display of devotional imagery, he said, “How will the people know (about Karbala) if they don’t see.”

Agha sahab’s statement suggests that imagery becomes a means to facilitate visualization of Karbala and this engagement with the image becomes a means of “knowing.” [36] In this instance, I am solely considering the viewers stationary encounter with the imagery, which allows the devotees to interact with the image, to look at it and/or read it. It allows for dialectical relationship or exchange to occur between the viewer and the image wherein the viewer through these actions attempts to make meaning about religious belief and historical events. These reflect back to the devotee as believer of a past that she has not witnessed, but which have a vast bearing upon her everyday life. On the other hand, the image is posited with sacred and spiritual, historical and political meaning, each time the devotee see’s the image, looks at it, imbibes from it. Agha sahab’s statement highlights the communicative aspect of the visual not only meant for members of the Shia community but also meant to reach out to the “other.” The ways in which this communication takes place through systems of representation is explored towards the end of this section.

A crucial ritual involved in the observance of Muharram is the setting up of sabeels in Shia neighbourhoods. For the duration of the month of Muharram, the street sides are appropriated to set up stalls that serve water

and other refreshments. These stalls are usually decorated with different types of Karbala imagery which range from large size flex banners to paintings of Shia religious iconography made on white or black coloured cloth. The

sabeel adorned with Karbala imagery not only demarcates space and are as a Shia neighbourhood, but it is a means of gaining visibility and asserting presence for a minority community which exists as part of a larger

Muslim minority in India. Figure 14 shows a sabeel installed near the ashurkhana Alawa-e-Sartauq in Hyderabad during Muharram (2010). This was organized by M.Husain and his family residing in the old city area.

Every year the family participates in this ritual of serving the community, by offering water and on particular days, food and refreshments to devotees and passersby. It is considered a pious act and a means of achieving

salvation. [37] Sabeels are set up either by an ashurkhana, an anjuman (men’s guild), by Shia families or other sponsors.[38]

Fig. 14 |

The sabeel in Figure 14 is dominated by a large banner depicting the battle of Karbala. It has verses

from the Quran written in Arabic, as well as a text in Urdu - “laakhon darood aur salaam aap par ya Husain ibn Ali” (we send millions of daroods[39] and salaams[40] to you, Husain). Beneath

it, the large fonts in green read “Ya Husain.” The background of the poster portrays an imaginary rendition of the battle of Karbala with several warriors mounted on horses. Blood is splattered in the background and on the text

depicting impending death and martyrdom. The white dove is a representation from a hadith (see above). The domes of Medina and Karbala are added to the multiple layers of imagery. Image and text have been interwoven

to create maximum impact upon the viewer. The area within the sabeel has been innovatively decorated with plastic surahi or water jugs in blue and green colour which are ornamental. The black and white banners

inside the stall display the names of the Prophet’s family and the martyrs.

Chromolithographs produced by the Ravi Varma Press and S.S. Brijbasi in the twentieth century, known as “Muslim posters” carried Shia iconography and symbolic representations such as renditions of the panja,

Zuljanah, Zulfiqar and Buraq. However these days community members (in the cities, ashurkhanas and Shia neighborhoods where research was conducted for this particular essay) increasingly opt to display

digitally produced Karbala imagery. This is not to suggest that the consumption of chromolithographs is entirely eradicated, but that for the purpose of use during Muharram, devotees prefer images produced using digital

technology, than chromolithographs prints. One reason for devotees choosing digitally produced imagery, is that chromolithographs primarily depict symbolic representations which have served well over the years as reminders of

certain events at Karbala, but their sparse visual vocabulary does not incorporate detailed scenes of the battle which would aid the devotee’s visual imaginary of the event. Another reason would be that the chromolithographs

were mass produced to cater to a wider group of Indian Muslim consumers. While, contemporary Karbala imagery is produced by artists and designers from the Shia community, who have some understanding of the religion and local

beliefs and practices. Thus, there is a certain personalization to its creation, as the consumers can request that a particular moment from Karbala or a martyr be depicted or certain text (mostly hadiths or poetry) be

added. It also pays closer attention to details, facts and events mentioned in hadiths that are rarely known outside the Shia community.

Social, political and cultural contexts determine the ways in which images influence or affect the viewer. Viewers consume, view and interpret images, make meaning ad consequently react to them. Images are made in accordance with

social, political and aesthetic conventions of the time. Visual codes are embedded in images, which the viewer then decodes without much thought, as these codes have been learnt and are second nature to the viewer.

[41] Historically, there has been opposition to figural representation within Islamic communities in certain geographical locations. However, these beliefs more commonly incited due to clerical injunctions have not always

been adhered to by community members, who have always found a means to incorporate images of their saints and prophets in their religious rituals. It is popularly believed that injunctions against figuration are not been based on

Quranic scripture but on hadiths, or the traditions of the Prophet. The hadiths offer two main objections; firstly there is a concern regarding the attribution of divine powers to figural imagery and

secondly, this is believed to be shirk.[42]

The designers and artists making Karbala imagery have found ways to side step this injunction on figural representation by using symbolic representations of Karbala, which work as signs. These symbolic representations have existed

long enough in the repertoire of Shia religious iconography for devotees to be familiar with them. Thus, instead of representing the figure of a martyr, certain objects associated with him from the battle of Karla are depicted by

artists. These objects work as signifiers. Such as the mashk represents Hazrat Abbas and Bibi Sakeena, the sword Zulfiqar represents Imam Husain, a panja would represent the Ahl-e-Bayt, and

Buraq represents Prophet Muhammed. These signifiers not only represent a martyr, but can also be indication of instances from the battle Karbala, such as the rider-less horse Zuljanah also indicates the martyrdom

of Imam Husain. Many times it is shown bleeding and pierced with arrows. Once the devotee sees the signifier, which works as a code embedded in the imagery, s/he is easily able to decode it and comprehend what, which moment of

Karbala or martyr is being signified.

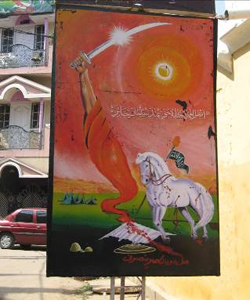

Fig. 15 |

Figure 15 is one such representation, here without depicting a scene with human figures the artist has managed

to represent the battle of Karbala in its entirety. The first thing one notices is the arm holding the sword which represents Imam Husain. The scene below shows the end of the battle, when Husain has been martyred, a wounded

Zuljanah is depicted with a battle standard which has the shape of a hand (panja) and a flag. This was carried by Husain’s army. Tents are seen faraway in the background. The painting conveys that the battle has

ended and Husain has been martyred and yet in his martyrdom, he remains victorious.

A study of visual culture using the theories of Semiotics limits the scope of the image and ends it at communication. It eliminates the possibility of the corporeal sensorium and relegates vision as foremost in the hierarchy of the

five senses. This has been noted in the works of several scholars working on the topic of the senses.[43] Hans Betling notes, “Images are neither on the wall (or on the screen) nor in the head alone. They do not

exist by themselves, but they happen; they take place whether they are moving images (where this is so obvious) or not. They happen via transmission and perception.”[44] By using the word

transmission he refers to the visual medium through which the image is transmitted. Perception refers to the senses, as he notes that the image impacts an individual on several levels. In this study, the involvement of other senses,

and how the image might go beyond mere communication was introduced by artist Syed Abraar’s quote.

Much before the use of digital technology, local artists were hired to paint scenes of Karbala. Syed Abraar is one such artist from Hyderabad who began his career making religious paintings on cloth and continues to do so even

today. He runs a studio called Abraar Art in the old city. Every year, before Muharram and on other religious occasions (such as the birthday celebrations –jashn- of the Imams) he is commissioned to paint cloth

banners or large curtains embroidered with names of the martyrs. More often these commissions are made by trustees of well-known public ashurkhanas. The function of imagery in the ritual context and what the artists try to

achieve through their works can be further understood by what Syed Abraar said in an interview: The purpose of this imagery is to create an effect of fear and foreboding in the viewer and to have them react to it.

“If one displays artwork on black cloth in the darkness, to look at it one feels fear, one can feel tears coming, goose bumps on the body, that kind of a state (kaifiyath) is born (in the viewer). When you suddenly see this

black cloth, with blood and weapons, it brings tears to one’s eyes. One can directly imagine [Karbala], so no one has to explain to the viewer [in detail]. If one is illiterate and does not know, then you have to explain to

them that this is the Imam and this is how he was killed. If they have been to a majlis and heard the program, then the moment they see this they can imagine [Karbala]. They won’t face a problem. Even during

majlis when a person reads about the tragedy from the book, the moment they look at the art they will be transported to Karbala. They are fully there. And now that the person has reached this stage, they cannot take the

pain and suffering and will start weeping. That [weeping] is the purpose (maksad).”[45]

Images can produce an array of emotions in the viewer and the viewer reacts to what s/he views. What these images represent is of the essence as we make meaning of our worlds by what we see, in just the way we use language to speak

of the world, to describe and to define it.[46] Thus in Shia religious practice, Karbala imagery is a visual language, a vocabulary to communicate history and belief. Karbala imagery not only conveys religious ideology,

but it represents, makes meaning of and conveys sentiments associated with the tragedy. Karbala becomes constructed in the viewers’ imagination by the majlis they attend, by the hadiths that are recited to them.

These visual representations in the form of Karbala imagery are an affirmation of what they have imagined about the tragedy. They fill the gaps in ones imagination and feed the vision that has formed in their minds. In this process

what occurred several centuries ago comes alive in the present. It becomes a dynamic history, very much a part of the everyday lived experience of the devotee. Karbala is a saga of enduring injustice in the form of pain, thirst and

hunger, finally martyrdom for the cause of humanity. Pain, thirst and hunger are experienced by the body. Thus, the devotees’ body would become involved in perception of any visual depicting the battle as what the devotees

imagines of Karbala will be experienced by the body in the mode of imagination.

Image, ritual and the corporeal sensorium

Fig. 16 |

Figure 16 is an image of young boys and men, performing matam in the old city of Hyderabad. In the background, there are stalls (sabeel) decorated with handwritten calligraphy on black cloth. The main procession in Hyderabad begins early in the morning after men gather at the Bibi ka Alam shrine. From here the procession, joined by other groups of mourners, traverses the old city, going from one shrine to the next and finally by sunset it reaches the banks of the river Musi. The community has made efforts over the years to maintain practices that originated during princely rule in the state. This includes details such as the procession following the same path every year, carrying antique standards (alams) which were made and used during the Qutb Shahi (1518–1687) and Asaf Jahi (1724-1948) periods. The main banner from the Bibi ka Alam shrine is usually carried by the shrine’s caretaker (mujaawar) on an elephant. Artefacts such as the royal umbrella (chattar/chattri) are also carried as part of the procession. The procession is also televised on regional and national television. These aspects of religious practice in Hyderabad attract devotees and viewers from other cities and rural areas who come to participate, or to merely witness the performance.

Fig. 17 |

Figure 17 shows the ashura procession held in Bangalore, as men holding standards (alam) walk

down the main street. In the background, on the left side, is a banner displayed in the street which depicts the shrine complex of Karbala. In this ashura procession different migrant groups form their own smaller

processions, which originate from a shrine or at a tent constructed for the preliminary gathering of men who read verses from the Quran. These processions then come together at the main street (Hosur Road) and progress toward the

local grave yard down the street, which is also called Karbala. Throughout the day the street is sealed and guarded by the police authorities. Tents are set up by the local medical clinic to offer assistance to injured mourners and

an ambulance usually follows the procession in case of people sustaining serious injuries.

T

he procession navigates the streets of the city or locality and finally by dusk stops at a water body or a local graveyard (also called Karbala) to “cool” (thanda karna) the alam. This means the alam at

this point in the journey will be laid to rest, symbolising the martyrdom of Husain and the end of the battle of Karbala. These public processions chiefly consist of male participants who perform matam, that is beating of

the chest with their hand or bloody matam (zanjeer ka matam or khama), self-flagellation with knives, swords, blades or chains until the mourner is at times is left bleeding profusely. Women

usually stay in the secluded space of the shrines or in their homes where they hold religious gatherings (majlis). They are seen watching the procession from the periphery – the street side, balconies, windows and terraces

of homes. The only way in which they can participate in the open is from this distance, chanting “Ya Hussain” with the male performers. Women are not allowed to perform matam in public.

The practice of bloody matam has been a point of conflict within the community and particularly in Hyderabad, with Ayatollahs of Iran and Iraq. Since the 1990s, several fatwas have been passed in both the countries against

the practice on bloody matam as it has been considered by some to go against Islam and that it has not been advocated by the Quran. The practice of bloody matam began in Hyderabad around the time after

independence, in the 1950s. Since then it has become part of what has been explained as “tradition.” During 2010 and more recently, every time I have questioned someone from the Shia community about the reason for the practice, I

have been told that through the performance of matam we intend to show our devotion and that “agar hum wahan hote, to hum Husain ke saath khade hote aur shaheed hote.” It means, had we been there (at Karbala)

with Husain, we would have stood with him courageously and fought in the battle with him and we would have been martyred with him. The participant performs a mimetic act by identifying with and undergoing the imagined agony of the

martyrs. The practice of matam can be interpreted as miming the suffering of the martyrs of Karbala. In order to mime the suffering endured in history, the participant inflicts his body arousing pain at the same time

imagining what must have occurred at Karbala. Sometimes the participant fells such fervour while performing matam, his actions with a sword or a zanjeer (chain) reach such a fevered pitch that people have to

intervene in order to stop him from doing grave harm to himself. A Shia cleric from Hyderabad explained, “When one feels pain, one reacts in different ways. Some react with a deep sigh, others with tears or merely a mournful

face. When one feels pain beyond endurance one beats ones chest in anguish.” Thus on the one hand matam is miming suffering, but one the other hand it may also be understood as an expression of grief. Both these

interpretations of matam are deeply linked with remembering Karbala, where the mimetic act is a means of working out the memory of Karbala and the body becomes the medium through which remembering occurs.[47] In

this moment, the participant embodies the qualities of bravery and courage of the martyrs.

This annual ritual not only commemorates Karbala and its martyrs, but it also reconstructs the narrative of Karbala in the present through the experience of pain and by visualizing the moment of injustice. Such a performance that

involves the evoking of memory occurs in a sensorial environment. The images on display become sites of recollecting and visualizing Karbala. The sabeels and particularly the banners depicting the battle of Karbala

transform the urban environment of the neighbourhood. According to Hans Belting, we differentiate between public and private media and each has a different impact on our perception and belongs to a different space. The space creates

the media as much as it (space) is created by them.[48] Flex banners are usually made to be displayed on the outside of a shrine, or a building or directly in the street, in open spaces. Particularly in the case of

Muharram, these banners as shown in the last section are displayed on sabeels and in the streets, competing for space with electric wires as much as with other images of advertisements. However, during this month, images of

Karbala are ubiquitous in various media, predominantly cheap synthetic flex banners, which is also the material used for banners advertising products. The images printed on this material are similar to ones that people view on the

internet, seen on their LED computer screens. So the images themselves already live in the devotees’ mental imaginaire. When displayed in public space, brought out into the open, they become part of the corporeal sensorium.

In urban environments such visuals add to the sensory bombardment a person experiences while navigating urban spaces.

The corporeal sensorium becomes further involved and is shaped by other elements of the procession described above. In such a setting the image is approached through action and affects the organism at several levels. The action I refer to here is that of matam, the physical act of mourning. An urban environment transformed by visual elements that impact the senses of the devotee evokes a sensory response from the devotee. Vision here becomes embodied as it leaks into the other senses.[49] The main element in this scenario is the experience of pain and the expression of grief. The body becomes central in our experience of images since it serves as a living medium through which images may be perceived, projected and remembered, so we can censor or transform said images. Images are transmitted through language, through language we imagine and form mental images. It is the body that makes images meaningful to us and brings them into the fold of our personal experiences.[50]

Karbala imagery serves a decorative function by framing the procession space as pious adornments. It becomes the background and a visual narrative to the performance of ritual pain in the street. But most importantly, the images

serve as a “conduit between beholder and deity.”[51] The emotions involved in mourning are fuelled by the images depicting the suffering martyrs. They depict grief as well as bodily pain (that was experienced by martyrs)

in the use of elements such as blood and the dying bodies of the martyrs. Most images analyzed in this essay conform to Michael Fried’s theory of “absorption.”[52] These are images where the subject does not directly

engage with the viewer, since the gaze is not directed outward, but is internalized. There is “absorption” or disconnect from the viewer. The gaze of the subject is either averted or does not exist. Then, how, does Karbala imagery

have a performative dimension?

The very act of making visual depictions of the tragedy and their consumption during ritual defines this as “ritual art” which functions as a medium between mourner and martyr. Furthermore, during a ritual performance there is

reciprocity between the subject of the image and the beholder (that is the mourner). At this moment, the performed ritual pain of the beholder is transferred onto the subject and in return the subject’s pain as imagined by the

beholder is embodied by her. Also, Karbala imagery does not depict deities, but martyrs, who were human and due to their endurance believed to be divine. While devotees do pray to them for intervention, they are rarely if at all

approached as Allah, in the sense that devotees do not offer prayers (namaz) before these images. Crucial to the ritual is the narrative of Karbala, the reiteration and recollection of injustice and suffering.

Hence, the imagery does have a performative dimension in ritual particularly when coupled with bodily performance. As explained in Christopher Pinney’s essay about the villagers of Bhatisuda, bodily performance before an image and

the passion of the devotee transforms “pieces of paper into powerful deities, through the devotees gaze.”[53] While, Pinney refers to a corporeal aesthetics, the possession of human bodies by deities which is mediated by

religious objects, particularly images of gods. Here, I refer to the intentional performing of self-flagellation in the presence of Karbala imagery or objects invoking the memory of Karbala. Even though the performer is not

experiencing “possession” by the image, visuality plays an essential role in the performance of matam, as scopic regimes become embedded in urban environments impacting sensorial experience that involves vision and the body

as medium of this experience.

I further argue that even when the gaze is “absorbed”, there is comprehension and interpretation by the Shia devotee who knows religious history. In images where the subjects face is turned away from the viewer, or rendered with

light (nur) and the gaze is non-existent, there is a visual connect between subject and viewer. In addition, there are other aspects of an image such as the use of visual symbolism and colors which are capable of arousing