Popular Image Practices at

The Shrine of Nizamuddin in Delhi

Continuity and Change in Iconography, Media, and Discourse

The Pilgrims and

Their Movement

Objects, Visuals,

and the Media

A Site of Ideological Difference

While the shrine of Nizamuddin is a 700 years old site, the area has attracted many more people (mostly Muslim) to inhabit the place, establishing their homes, shops and mosques of various sizes. One of the recent additions in the vicinity is a large mosque named “Banglay Wali Masjid” (lit. a mosque of the bungalow) which houses the headquarters of an apolitical religious movement called the Tableeghi Jam’at (lit. a gathering for dissemination) meant to spread a reformative Islam that is averse to the culture of Sufi shrines, grave veneration and hybrid rituals. Tableeghi Jam’at was founded in 1926 by Maulana Ilyas to work at the grass roots level to reach out to the Muslims to bring them closer to the life practices of prophet Muhammad. This centre attracts a large number of Muslims from India and abroad (who may not like to call themselves pilgrims or devotees, although their devotion is not without a sense of pilgrimage). These tableeghis come and stay in the mosque for a few days, praying and listening to reformative or moral sermons, and then move on to other near or far away mosques in groups of 10 or more to spread the message further. Naturally, their presence in the locality makes available a large variety of ephemera of printed literature, calendar art, items of prayer, and so on, which in many ways is supposed to be antithetical to the concepts of Sufi shrines.

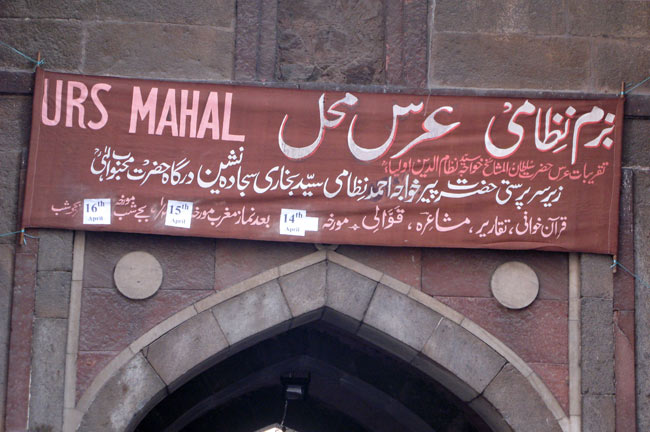

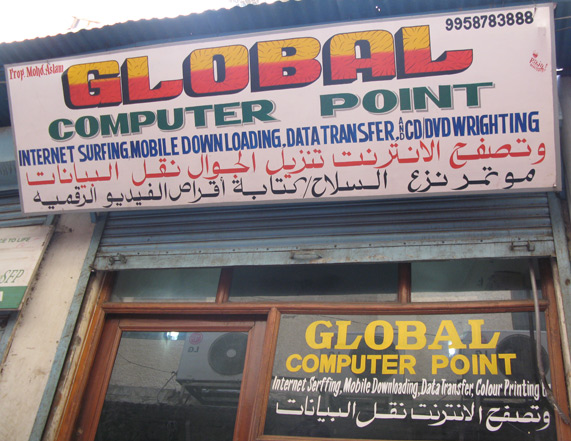

The most important and visible difference one can notice here is the local rooted-ness of the Sufi pilgrimage centre contrasted by an “international” and sanitized character of the tableeghi centre (due to many foreign visitors from Arab, African or Southeast Asian countries). However, the third shrine, that of Hazrat Inayat Khan, (although not so relevant for this project, since its quiet presence does not affect the locality in any significant visual way) presents a very different level of “foreignness” since its devotees are mostly westerners whose occasional presence in the common market or main dargah of Nizamuddin is more an act of curiosity or quiet meditation rather than to participate in the visual culture of the bazaar. Thus, the contestation of the visual cultural practices between the Sufi centre and the tableeghi mosque can be seen as the most significant asymmetry with which one is studying the locality during this project. What is mainly being explored here is the changing dynamics of the printed literature and wall/street hoardings as they inform, educate, attract or geographically inter-connect and transport the pilgrims across the shrines, sects and ideologies within Islam and Islamic world.

The most important and visible difference one can notice here is the local rooted-ness of the Sufi pilgrimage centre contrasted by an “international” and sanitized character of the tableeghi centre (due to many foreign visitors from Arab, African or Southeast Asian countries). However, the third shrine, that of Hazrat Inayat Khan, (although not so relevant for this project, since its quiet presence does not affect the locality in any significant visual way) presents a very different level of “foreignness” since its devotees are mostly westerners whose occasional presence in the common market or main dargah of Nizamuddin is more an act of curiosity or quiet meditation rather than to participate in the visual culture of the bazaar. Thus, the contestation of the visual cultural practices between the Sufi centre and the tableeghi mosque can be seen as the most significant asymmetry with which one is studying the locality during this project. What is mainly being explored here is the changing dynamics of the printed literature and wall/street hoardings as they inform, educate, attract or geographically inter-connect and transport the pilgrims across the shrines, sects and ideologies within Islam and Islamic world.

In Nizamuddin, one can find a tableeghi pilgrim from Indonesia buying caps while a perfume shop announces its presence in Arabic for their Arab clients. More visible are of course hawkers selling amulets in different shapes and colours. Then there are a large number of cheap hotels in the vicinity (with tiny rooms for pilgrims), and many travel agents promising attractive tours to places where similar shrines exist. The presence of travel agents and their “devotional tour packages” indicates further travel needs of the middle- or lower-middle class families visiting from far away places. In many cases, Muslim pilgrims coming from places such as south India (Andhra, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka) or Bengal and Assam arrive first in Delhi and wish to travel further within Delhi as well as to places like Ajmer or Agra, and avail the services of these tour agents. Nizamuddin area also has its own railway station nearby, where usual as well as special trains for pilgrims arrive and depart. Thus this shrine and its vicinity is really a unique centre of cultural mobility and shifting asymmetries. The visiting pilgrims need to take back some souvenirs, literature or items of devotion that have special relevance for having been purchased from the shrine of Nizamuddin. Thus the movement of ephemera and available information via the pilgrims helps in a cross-cultural flow, which is not always symmetrical due to the ideological differences.

In Nizamuddin, one can find a tableeghi pilgrim from Indonesia buying caps while a perfume shop announces its presence in Arabic for their Arab clients. More visible are of course hawkers selling amulets in different shapes and colours. Then there are a large number of cheap hotels in the vicinity (with tiny rooms for pilgrims), and many travel agents promising attractive tours to places where similar shrines exist. The presence of travel agents and their “devotional tour packages” indicates further travel needs of the middle- or lower-middle class families visiting from far away places. In many cases, Muslim pilgrims coming from places such as south India (Andhra, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka) or Bengal and Assam arrive first in Delhi and wish to travel further within Delhi as well as to places like Ajmer or Agra, and avail the services of these tour agents. Nizamuddin area also has its own railway station nearby, where usual as well as special trains for pilgrims arrive and depart. Thus this shrine and its vicinity is really a unique centre of cultural mobility and shifting asymmetries. The visiting pilgrims need to take back some souvenirs, literature or items of devotion that have special relevance for having been purchased from the shrine of Nizamuddin. Thus the movement of ephemera and available information via the pilgrims helps in a cross-cultural flow, which is not always symmetrical due to the ideological differences.

Metcalf, Barbara D.: Living Hadith in the Tablighi Jamaat, in The Journal of Asian Studies 52, no. 3 (1993): 584–608

Next >>

Map

More images from

the Shrine

Video clips