Observations, Conclusions of the project

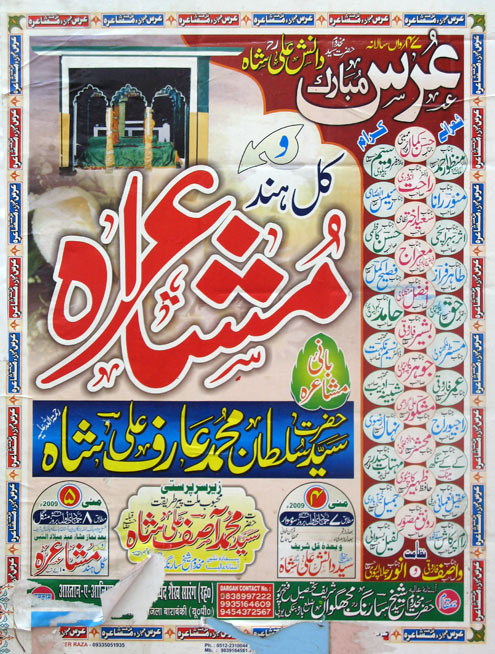

[Urs mubarak wa mushaira: An announcement poster (found on a wall near Nizamuddin shrine in Delhi) about the death anniversary celebration and poetry session in Majhgawan, Barabanki, UP. Photograph by Yousuf Saeed].

Ishtehars or Announcement posters around the shrine

Indian street walls have been the most basic media for communication of all sorts of messages whether political, commercial or religious. Earlier, it used to be mostly hand-painted slogans or information about events in limited number of places where it was possible to paint without raising anyone’s objection. But the printing of temporary posters and pasting them on the walls made it possible to quickly place them at much wider and larger number of places without being discovered by someone who might object to them. Thus, the announcement posters of Islamic events being held in far away places can now be found in unexpected corners simply because of the new networks of pilgrimages that are emerging now due to better connectivity of travel and media. Secondly, the several events related to different ideological stands can also be seen on the same walls or localities. During this study, one could see notices announcing events of multi-faith dialogue (sarva dharm sammelan), or “conferences” incorporating various Sufi sects. There are posters of Bareilly (UP), Seelampuri (east Delhi) and even far away Karnataka (Chittagoppa, Bidar). But the most fascinating is an information sticker from Karachi, Pakistan, inviting Indian pilgrims to a conference on Sufism! Even if no one travelled from Delhi to Karachi after watching the announcement, the posters and stickers at least make cross-cultural connection between regions and countries, or creating a sense of the ummah (or Muslim community), which is not based on a puritanical or sanitized notion of Arabicized Islam, but a diverse and colourful network of Sufi-related events.

Devotional Discourses in Popular Video CDs

Most of these video narratives seem to create authority and credibility for the shrine and the saint among the visitors by eulogizing the spiritual and miraculous powers of the saint, and often give a symbolic call to the prospective pilgrims to visit the shrine from near and far. Peter Manuel in his Cassette Culture (1993) talked about the evolution of India’s music cassette industry and how it has transformed north India’s popular culture. Although Manuel’s analysis still holds true in many spheres including the religious narratives, the technology has rapidly changed. From the audio cassette culture, we have now graduated to the age of videos and VCDs. This seems very important since the role of religious practice in the emergence of public spheres in India – and across the globe – and vice versa – seems crucial. The pattern of group-watching of these videos is the same as in the conventional sermon or enactment discourses. During this research, we interviewed various producers and users of the devotional videos. The ease with which a video CD is produced today by using a cheap DV camcorder and a computer, has given birth to newer forms of visuality which were not possible in the days of the bulky and expensive analogue video and VHS. Many older Qawwalis and devotional songs are being recycled in their new visual avatars using brightly coloured sets, costumes and video inserts. The medium is also empowering many young and aspiring musicians/singers to jumpstart their careers using VCDs, something that is yet to be studied in more detail.

Nizamuddin Shrine’s heritage buildings and Delhi’s urban facelift

In a city that is home to the rule of over 10 dynasties in the last one millennia, India’s capital Delhi is strewn with heritage buildings all over its length and breadth. With a bulging population and new infrastructural growth, there has been tremendous pressure on the surviving historical monuments, many of them having been demolished or damaged in the last one hundred years. The shrine of Nizamuddin Aulia is one of the rare cluster of buildings that have been in continuous use by local residents, devotees and priests, adding new structures for their use every few years on top of the older buildings without much concern for the conservation of heritage. However, the government agencies and heritage conservation groups who have tried to restore or conserve Delhi’s other buildings, have been concerned out the dilapidated condition of the shrine. Recent efforts by the Delhi government and the Agha Khan Trust for Culture (AKTC) yielded some results as at least the nearby buildings (such as the Urs Mahal and the Baoli step-well) have been cleaned up and restored to some extent. But these efforts met with a lot of resistance from the local residents. The AKTC had to convince them by initiating a much wider development project involving a cleanup of the streets and sewage, and providing the residents facilities of health, education and activities for children and women. They even held cultural events such as Qawwali evenings and visual exhibits showcasing the history of the site and how it has changed over the centuries. In some cases, these activities projected the Sufi shrine with stereotyped exotic images of faqirs and devotees – a representation that is often used by the media and tourism industry to showcase Sufism and Sufi music through certain high-class events and heritage walks. All this activity created its own visual culture that incited the curiosity of the local residents who came to see the exhibits and the “restored” sites, and probably found “new” meanings of visual heritage in older buildings.

Connections with other shrines on the map of South Asia

Through the movement of pilgrims and what images/ephemera they buy, we tried to look at the flow of visual/printed material going to and fro between shrines and regions. A specific multimedia module we are working on is a map of Delhi/India/ South Asia showing the location of specific shrines and the connections between them in terms of the routes followed by different pilgrims and how images and information flows between them, especially through posters, smaller prints and now the videos. An interesting link we have found for instance is between 3 zones – Lucknow/Deva, Delhi and Ajmer, where most of the pilgrims visit. Many images and media discourses from the three shrines travel between each other and make a complex geographical as well as ritualistic connection for the pilgrims. We explored more research and documentation work conducted by other scholars on specific Sufi shrines and trying to connect them to our theme. At least one study worth mentioning here is the research/documentation work by Subah Dayal and Suzanne Schulze for Tasveer Ghar, titled Outside the Imambara: The Circulation of Devotional Images in Greater Lucknow, available on the webpage: www.tasveerghar.net/cmsdesk/essay/76/

Summary of findings/conclusion:

Among the findings, it was discovered that the use of print and electronic media for announcements as well as devotional discourses has affected the expansion of Sufi shrines and pilgrimage routes at various levels. In old times, the pilgrim movement and devotion across geography was limited to specific shrine centres that were within their knowledge or popular discourse. But as more posters, audio and video narratives are being produced, sometimes about hitherto completely unknown shrines, the devotees are getting to know about much wider circuits of travel that they can now embark on, including trans-national routes such as between Pakistan and India or Bangladesh and India. The improving economy of India and better means of transport (including the local travel agencies) have also allowed the devotees to travel to newer sites. The video and print discourses also add newer rituals and mythologies about the shrines and saints in their religious experience. But these discourses are not homogenous, nor only about the Sufi shrine culture. Some of them are also religio-political speeches by reformist speakers who are normally against the Sufi shrine culture in Islam. But interestingly, neither the shops around the shrine make any differentiation while selling these videos nor the devotees/buyers find the antagonism between the different ideologies, and buy them with curiosity. Thus, a peculiar amalgamation of religio-political identity involving the local and the global Islam can be noticed in the visual discourses available around the shrine of Nizamuddin in Delhi.